How to turn garden plants and weeds into perfume

It seems every celebrity has their own scent to sell, but you could make your own with a unique Kiwi flavour.

Words: Jane Wrigglesworth

Perfumes have enjoyed high regard in every era, from the earliest frankincense and myrrh offerings, to the celebrity fragrances of Beyonce and David Beckham.

Today, it’s even more so if the ingredients are natural. Global sales of natural cosmetics were close to $US30 billion in 2013, growing by 10.6% according to research by the Kline Group (2014), and continue to grow ahead of the average rate for the cosmetics industry as a whole.

It’s something you might be able to take advantage of if you head into your own backyard and find a plant with a perfume – subtle or otherwise – which acts as an aromatic ‘tonic’. Bottle that scent by way of distillation, tincture or enfleurage and you could find yourself in the perfume business.

Artisan perfume maker Vanessa York creates enticing scents in her micro-perfumery in Waiake on Auckland’s North Shore. Her perfumes contain no synthetic products, but the raw scents can be as beautiful and evocative as perfumes that do contain synthetics, she says.

Anyone can make natural perfumes from plants in their backyard. Flowers, foliage, seeds, bark, resin, roots, rhizomes and rinds can all be used. Even weeds can be turned into remarkable scents.

“Jasmine, honeysuckle and wild ginger flowers all smell amazing,” says Vanessa, “And by harvesting the flowers you’re also helping to stop the spread of these pest plants.”

Jasminum polyanthum.

If you look at the price of jasmine absolute on the market, you might think you’re on to something. For 25ml you’ll pay around NZ$370.

But the sheer volume of blossoms needed may put you off. It takes up to 1000kg of jasmine flowers to make 1kg of jasmine absolute – or 8000 flowers to make 1 gram – and they must be hand-picked in the dark and early morning when the perfume is strongest.

Also, the two jasmine flowers that are mostly used to make absolutes are Jasminum grandiflorum and Jasminum sambac, neither of which we have here in NZ. What we do have is the weed Jasminum polyanthum, although it’s not (yet) on the National Pest Plant Accord and in many parts of New Zealand it’s not officially a pest plant.

NZ also has Jasminum azoricum, and both of these plants can be used in perfume, though they won’t deliver the same notes as the two more powerful ones (grandiflorum and sambac). However, a Jasminum polyanthum extract derived by enfleurage is available on the Australian and UK market, with a 10ml extract priced at $AUS128.

Adam Michael of Hermitage Oils describes it in flowery terms.

“This material is the most enchanting and soulful floral I have experienced this year. The aroma is a summer breeze of soft, delicate, harmonious, Italian grown Jasminum polyanthum flowers. The Italian producer in my heart is an artist and this joyous material is a labour of complete dedication and absolute unequivocal love. The result is a spiritually comforting aromatic masterpiece.”

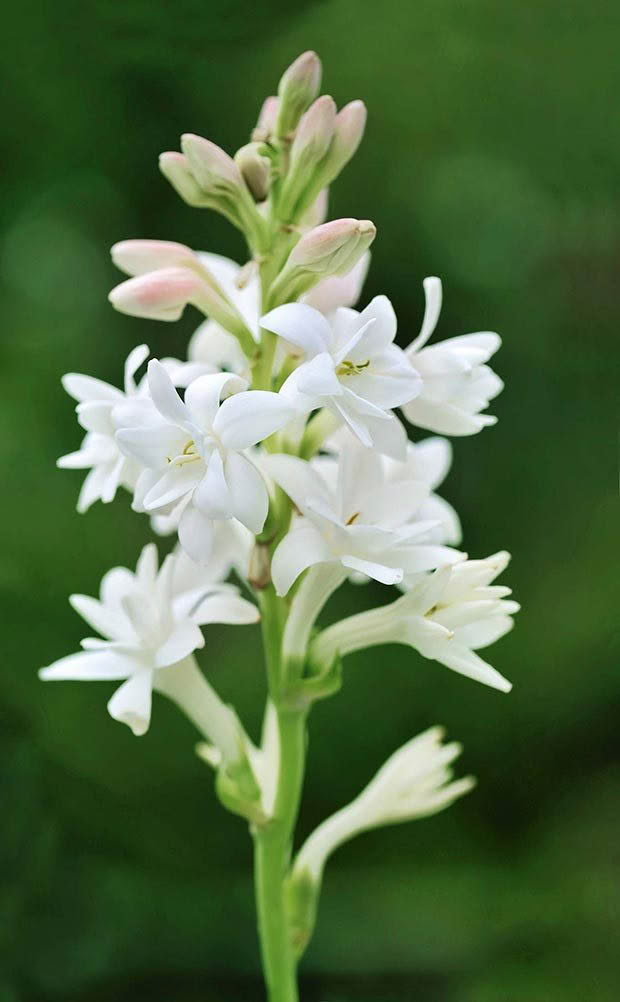

Tuberose.

Enfleurage was a method traditionally used for flowers such as jasmine and tuberose which are too delicate for distillation, or where the flowers continue to produce volatile oils after being picked.

Harvested jasmine flowers, for example, produce 4-5 times more volatile oil than is present at any time in the fresh flower, and tuberose up to 12 times more. If distillation was used, the heat would destroy the flowers and the still-producing scent.

“Delicate flowers such as jasmine and tuberose do give up their scent more readily and beautifully to enfleurage,” says Vanessa. “It’s a very time-consuming method however, and labour-intensive; you need to recharge the flowers up to 20 times.

Tincturing is much more straightforward – prepare the materials, cover with alcohol, and shake every day. Some tinctures are ready to use in a couple of weeks, others take months,and may go on improving for years. It gives wonderful results with some materials, and disappointing ones with others. I’ve found jasmine tinctures disappointing, myself.”

Although time-consuming, there could be a market for enfleurage in New Zealand, but consider the process first. Adam Michael describes the method undertaken by the Italian makers of the Jasminum polyanthus extract.

If you are looking to sniff out a commercial opportunity on your block, a unique NZ fragrance might be an option.

“The freshly-opened flowers only are picked in the evening when their scent is pretty intense and gently laid down on a tray with a very thin layer of wild shea butter smeared on it. The flowers are then allowed on the fat for maximum 24 hours and then replaced with fresh ones, and this process is repeated at least 20 times. This way the fat absorbs the scent exhaled by the flowers without using any heat that would inevitably damage the most delicate odour compounds. The scented fat (the so-called ‘pommade’) is then washed in food-grade ethanol (96%), shaken daily for three weeks until the alcohol is saturated with its scent. Finally the alcohol-fat mixture is drained to remove the now scentless fat, whereas the alcohol gets repeatedly filtered leaving us with the so-called ‘extrait’ (extract) from enfleurage.”

In perfume processing factories in France in the 19th and 20th centuries, a mixture of beef fat and lard was used. A 50-80cm square glass plate in a wooden frame was smeared with the animal fat, and the flowers – minus their calices – were laid on top. Several of these frames were stacked on top of one another.

You can see the process carried out in the 2006 film Perfume: The Story of a Murderer when lead character, Jean-Baptiste Grenouille, goes to Grasse, the home of the perfuming craft, and learns the process of enfleurage.

After the requisite period of time, the flowers were removed and fresh flowers were laid. This process was repeated, up to 30 times, until the fat had absorbed the fragrance.

The enfleurage process is ideal for extracting the fragrance from jasmine and other flowers, like tuberose and lilacs, but it’s a long-winded process. The modern method extracts these scents with the use of solvents, like grain alcohol or hexane at a low temperature. The hexane is then removed or the alcohol allowed to evaporate and you’re left with the oil.

Perfumes can be made as solids, oils, creams, colognes and sprays, using various bases and whatever extract or extracts are applicable to the product.

If this all sounds too lengthy or complicated for you, tinctures and infusions are a simpler means of extracting scents from botanicals. Herbalist Donna Lee of Cottage Hill Herbs in Upper Hutt runs a perfume workshop that utilises organically-grown herbs.

“There are many, many herbs and spices that may be used to make perfumes: anise, cinnamon, vanilla, cardamon, balm of Gilead, fragrant pelargonium, lemon grass, lemon balm, mints, citrus, sweet woodruff, angelica, including flowers, leaves, fruit, root and seeds. They can all be tinctured into vodka or witch hazel or perfumer’s alcohol, and also made into hydrosols, infused oils or pressed into fats and extracted that way.”

You could also try your hand at extracting essential oils. “The beautiful pure essential oil of melissa, for example, is more powerful than the fresh herb – a small bottle of essential oil requires around 70kg of leaf for extraction by steam. It is powerful, but very gentle, having wonderful anti-inflammatory properties, plus its anti-viral wonders, so is useful in creams, ointments and lip balms, etc.The gentle hydrosol is also most beneficial for skincare.”

Perfumes can be made as solids, oils, creams, colognes and sprays, using various bases and whatever extract or extracts are applicable to the product.

“Essential oils, infused oils, tinctures and hydrosols can be added, for instance, to create a cream perfume with intensity of fragrance and can equal, in my opinion, an expensive store-bought perfume,” says Donna. “Fragrant oils (phthalate-free) may also be used in combinations with pure essential oils, as this is how perfumes are created.”

Vanessa, who also runs perfume workshops, mainly uses essential oils, resins and absolutes to scent her natural botanical perfumes, with the occasional unusual fragrance such as seaweed tincture and birch tar. But she also has a passion for developing a specifically New Zealand perfume culture. She’s one of four artists-in-residence at Studio One Toi Tu in Auckland, where she is pursuing her interest in New Zealand perfumery.

Lavender grown in NZ smells different to lavender grown in France, Spain or England.

“Part of my project as an artist-in-residence this year is seeking out new perfume materials, both indigenous and introduced. I’m interested also in scented plants and flowers grown and processed here. Some people don’t realise that flowers reflect terroir. So, for example, lavender that’s grown here in New Zealand smells different to lavender that’s grown in France or in Spain or in England.”

If you’re looking to sniff out a commercial opportunity from botanicals grown on your block, why not look to natural New Zealand scents? Much like NZ-grown sauvignon blanc wines have found favour on the international market, it’s possible the fragrance of a NZ-grown plant could do the same thing.

Vanessa recommends asking professional perfumers what they might want, and getting insight from the cosmetic, toiletry and candle industries.

“Avail yourself of the wealth of knowledge in the community; there are some really helpful Facebook groups, and perfume forums, for example, with professional perfumers happy to help.”

And take a course.

“As with any art or science, it takes time and practice to gain skill. Attend a workshop or a class; you will learn a lot in a short space of time and it will give you confidence to start your own experiments.”

DISTILLATION

Steaming plants, vaporizing the liquid, then cooling and condensing the vapour and collecting the resulting liquid.

TINCTURE

A remedy made by soaking plants in alcohol.

ENFLEURAGE

A method that uses fat to extract the fragrance from petals.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.