Travel essay: How cleft palate operations are saving lives (and smiles) in Kenya

Not every baby is born with the ability to smile. Cleft palates are a heartbreaking but treatable condition. In Kenya, one photographer documents the mothers and children that make their way to surgery as they embark on a journey of hope.

Words and Photos: Chris Van Ryn

A matter of hours after I photograph eight-month-old Abdul he dies. The surgeon informs me of his death via WhatsApp: “Chris, Abdul passed on in ICU at 8pm tonight. The past four days have been hectic for me as I worked tirelessly with the ICU team and paediatrician trying to save his life – to no avail.”

Abdul had a cleft lip and palate; babies born this way struggle to breastfeed. They can’t hold on to the nipple. Mothers pour cow’s milk into the gap where their lips don’t meet.

The babies gurgle and cry as milk froth comes out their noses and mouths, drips of white run down their chins and everything ends up in a mess on their laps. The baby becomes malnourished. Haemoglobin is low. The lip can be stitched together during surgery.

Abdul and his mother made the long journey from Somalia to Kenya for an operation that turned from hope to tragedy.

But the anaesthetic, administered on such a small, undernourished frame, can kill.

The doctors make a call: if the lip is stitched, the baby can breastfeed, become nourished and feel the closeness of the mother, her warmth, the heartbeat transmitting the rhythm of love – vital elements for human development. But sometimes the call to anaesthetise a slightly under-par baby is fatal.

In the Nairobi hostel where I’m staying, I reread the text and study the photos of Abdul. I think of his mother and her journey from Somalia to Kenya, and the trail of tears that trace her grief on the arc of her cheek.

I think of Abdul in his little red Santa-like outfit, crying through his cleft, leaving a long dangling thread of saliva as the IV is inserted.

I am working as a volunteer documentary photographer and writer. I photograph children like Abdul. I investigate their short, disjointed lives and write stories and send them to agencies in America and Germany, which use them when seeking funding.

In Amboseli National Park, two giggling Maasai children walk home – the girl (10) is married.

America wants images without tears – clefts before and after successful operations, delivered with a smile. Germany wants tears and trauma – raw and visceral.

My room at the hostel has an en suite but no hot water. The cold trickle fills a red bucket which, after lathering up, I tip over myself. Nairobi cools in the evening. Each time the water slaps my chest, I shiver involuntarily. Toughen up, I think.

I’ve arrived in Kenya at a difficult time. Anarchy overshadows democracy. Gang violence and political tension is in the news and on the street. Muslim students machete Christian students.

A man is beaten and robbed at an ATM while people stand around watching. An ivory-poaching activist is murdered and hundreds of illegal tusks are piled up in Nairobi’s national park.

A car from Somalia, loaded with grenades, is intercepted en route to Nairobi. Sniffer dogs and X-ray machines and mirrors that scan the undersides of cars are at mall entries. Everyone knows someone who’s been mugged. Houses are in compounds protected by razor wire, large gates and security guards.

Alex Ombesi’s mother shows her delight with the cleft operation. She gave birth to her first child at 14, and is a solo mother working in a roadside kiosk.

And then there’s Kibera, Nairobi’s central-city slum, home to an estimated 1.3 million. From the air you see a vast panorama of back-to-back corrugated shacks, a patchwork of rusty roofs under which the hopeful, the violent, the disenfranchized, the corrupt, the hustler, the criminal, the inter-tribal fighter, the rapist, the seropositive, the Muslim, the Christian, the refugee and the terrorist amalgamate into one great despairing unicellular human organism.

Over the next five weeks, I travel 2000 kilometres. I visit the parched plains of Amboseli in search of one particular newborn belonging to the long-limbed, brightly-robed Maasai, and visit hospitals in locations across Kenya, near the border with Tanzania and Uganda.

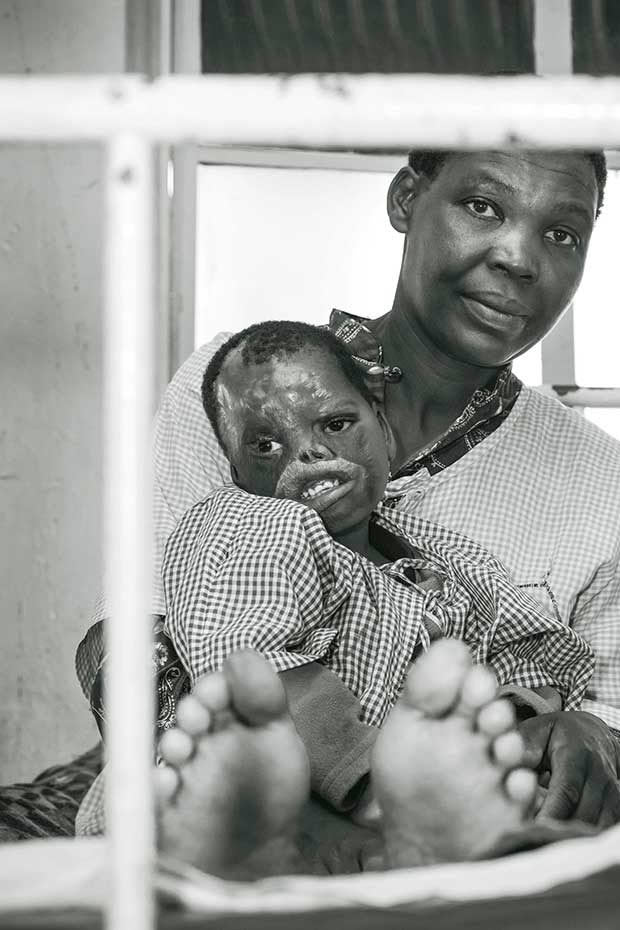

Deformities are intergenerational – this mother and child, her brother and father all having cleft lips and palates.

In a hospital in Bomet district, my nostrils fill with the heavy odour of unwashed feet and armpits and hair and clothes.

The air is thick, motionless and weighted with apprehension. There are rows of crude metal-framed beds lining the walls like a dormitory.

Above each is a mosquito net, wrapped in on itself like a hair-bob. Below one is a teenage girl. She lies listless, with an empty stare, arm outstretched, hooked up to an antimalarial drip.

At the other end of the ward is a raised hand, like a question. When I go over, I see it is badly burnt, covered in blisters and greasy ointment.

A young woman with rapid shallow breaths is the one who poses the question. Actually, it’s more of a statement. Crude wood fires, and paraffin and kerosene cookers, have resulted in an epidemic of burns. They are Kenya’s overlooked traumas.

I photograph her. No, I don’t. I photograph the hand. I check the image. This looks like something from a Stephen King movie. And then I think: What the hell is wrong with me?

There are 18 babies awaiting cleft operations. Nurses are taking blood samples and preparing IVs. It’s not working well. They can’t find veins. Babies are sobbing. No. Screaming. Retching. It’s chaos – a rising crescendo of tears.

I record it: a discordant symphony, the sound of a miserable life start.

A young woman shows the characteristic branding of the Maasai, a circular burn on both cheeks, made with a crude wire branding iron – one cheek at age two, the other at age five.

A nurse attempts to get a blood sample. He tightens a rubber glove around a baby’s arm, inserts the needle but draws a blank. He swaps arms. The child is screaming and writhing. No luck. He tries above the foot, slapping it several times, trying to swell a vein before inserting the needle. Still nothing.

Competence is nowhere to be seen. The baby is in great distress. The mother covers the baby’s eyes. The nurse calls for support.

They pull off the nappy, so now the little brown body is naked from the waist down, legs akimbo. I head outside as the needle approaches his groin. I sit in a small garden, next to three squat toilets that reek.

I document wet cheeks and lips with webs of saliva and, like a back-alley addicts’ wasteland, syringes and dripping blood trails and used gauze and discarded rubber gloves and needles, and at one point a cringing, crying child shifts his eyes from the syringe that’s sticking out of his hand to my camera, a look that shoots down my lens like a bullet and refracts off the mirror and reaches me through the viewfinder so that he and I are locked. In distress.

In anguish. Pupil to pupil. Retina to retina. Heartache to heart.

I press the shutter.

A Maasai mother with her child who had undergone a cleft-lip surgery funded by Smile Train. Stage two is palate repair.

In Kitale, Bernice, a 15-year-old with troubled skin, has a six-month-old with a cleft lip. She’s been fortunate. The baby could breastfeed. Actually, no. A pre-op exam revealed Bernice is seropositive; now, through breastfeeding, so is the baby.

I meet a two-year-old. A girl, I think. I can’t tell. Then I see a little pleated skirt. At six weeks old her face melted. Her lips are smeared like those of a grotesque clown. Her right hand had shrivelled so doctors removed it.

Her left hand has contracted into a permanent fist. Her right ear is now an unhearing flap. When asleep, the inside of her eyelid reveals a blood-red flap of flesh.

Her name is Shirleen. Left alone in the house by an alcoholic father and a psychotic mother, a curtain blowing in a breeze caught fire.

I photograph Shirleen between the metal bars of the bed end, like she’s imprisoned. She is. Trapped inside a face that will prescribe her future. I reach out to cradle her in my arms but she twists and turns, resisting. Later I see her trotting around the ward, laughing like a demented Halloween mask.

She does not know yet what she does not know.

Shirleen is one of many burn victims – Kenya’s overlooked tragedies.

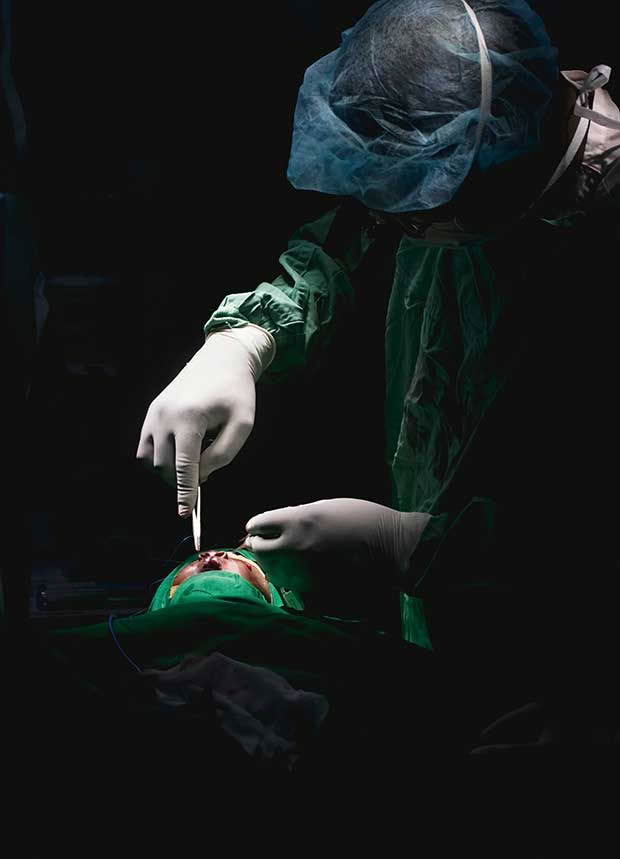

“Put this on,” says a nurse, handing me a mask and cap. St Elizabeth’s hospital in Kakamega. I’m near the end of my tour.

Unexpectedly, I’m ushered into theatre. The room is dim and cold. There are fluttering fluorescents and peeling paint on the ceiling and walls. It feels like a bunker.

On the operating table is a small torso covered in green fabric.

The head and the matchstick limbs protrude. A monitor beeps in the background, its screen flickering.

Ronald, the surgeon, is sitting on a stool at the head of the table surrounded by his team. There’s Francis and Kodia: nurses.

The anaesthetist is Mwanza. And there are other green-garbed people, leaning over this little body.

All unpaid volunteers, who work tirelessly for three days, four or five times a year, on babies they don’t know and will likely never see again.

The infant’s tiny pot belly rises and falls in a gentle, regulated rhythm. Mwanza pumps a small green balloon attached to a life-giving tube that disappears down the baby’s throat. At the same time, he scans Facebook.

The overhead operating light ignites, sending out a narrow beam, like a searchlight. It sets the infant’s cleft lip glowing. I take my camera and adjust the settings so that through the viewfinder the background and people recede into deep shadow.

All that remains is the spotlit baby with its gaping lips and the white rubber gloves which hold tweezers and scalpels.

A Maasai mother breastfeeding her child, who slips seamlessly between sleeping and sucking.

The operating room becomes a stage, the gloves the performers.

Six white hands with 30 white fingers all working in unison, each finger a little ballet dancer, the operation an elegant 45-minute choreographed performance of unparalleled beauty.

I put the camera down. I scan the partially concealed faces. I see narrowed eyes and creased brows and gloved hands and tweezers and scalpels. The theatre has become very still.

Everyone is leaning in towards the little brown head. Kodia hands Ronald a pair of hooked tweezers, just before he needs them.

Francis deftly dabs away a blob of red. Mwanza keeps pumping. Ronald twists a silky suture tight.

It glows golden, this final thread that pulls lips and lives together.

In that moment at the operating table, I see everything that is good about people, about being human, about humanity caring for humanity. “You guys …” I reach into the silence. “…you guys are amazing.”

Ronald looks up. Other eyes swivel my way.

I can’t see their mouths but I swear they’re smiling. No one says anything.

I rub my eyes with the back of my hand, pick up my camera – and head back to Nairobi.

I’m done. I switch off my camera and remove the batteries. I place it in the wardrobe of my hostel room like it’s an infection. I have 3000 digital encryptions of trials, traumas and triumphs. I sit on the edge of my bed. I look in the full-length mirror. I try to unpack myself. To examine my emotions.

The best time to view animals is at dawn.

I head for the shower. I can’t wait to get this dust off. I draw the curtain aside. The red bucket stares at me. I flick the tap and crumple my trousers around my ankles. Wait. What’s this? The mirror has fogged over. OMG.

I stand and bask in the surprise of hot water for 10 minutes. I get out. Twenty minutes later I get back in. I turn up the heat and feel it soak into me.

My mind replays the past five weeks. I see Shirleen entombed in a mask – she will never bring her lips together against those of another – and a seropositive baby looking at a lifetime of immunosuppressant drugs, and the little limp corpse of Abdul.

I think about the ‘statement’ hand and the crescendo of tears. I walk through Kibera, the slum of lost hopes and rapes and premature pregnancies and unsanctioned abortions. I wonder about the thousands of children born and yet to be born with inbred cleft lips and palates and… Me, I’m heading home. I begin to cry.

HOW TO HELP

The agencies I worked for were:

◊ Smile Train based in New York. It recently completed one million cleft operations worldwide. By July/August, Smile Train in Africa will have attended to 100,000 cleft patients. See smiletrain.org for more stories, how to get involved or to donate. As little as US$250 gets one child an operation.

◊ Cleft Kinderhilfe in Germany assists in cleft lip and palate operations in India, Pakistan and Kenya. Cleft Kinderhilfe has also opted to assist in funding the operations that Shirleen (see main story) needs.

Together with a small foundation I have established for burns victims, we have actioned five operations which will take place in Kenyatta National Hospital.

She will have her lips, hairline, hand, ear, eye and nose operated on. It will never fix the unfixable. But she’ll be able to write, breathe more easily, hear better and her lips will look less clown-like.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.