The ultimate guide to pruning your fruit trees correctly

The good news is that poor pruning is like a bad haircut – it will grow out.

Words: Sheryn Dean

Trees don’t care how they look. People struggle and stress over pruning choices but understanding the why and what makes it simpler. You can’t really stuff it up and kill the tree, although you might miss a harvest.

WHY PRUNE?

You don’t prune for the benefit of the tree.

Humans believe that we must prune fruit trees. But trees are quite happy if no-one comes along and amputates their branches every year. They survived for millions of years without the need for chainsaws or secateurs.

Pruning is a relatively new practice developed in the last 100 years, mainly to make harvesting more cost-effective.

The main reason you’ll prune a home orchard is for convenience, so you can:

• get the mower past;

• reach the fruit;

• fit more trees into a smaller space;

• remove diseased/damaged branches.

Bad pruning can be disadvantageous for the tree; some judicious snips can be beneficial.

PRUNING AT PLANTING

It’s beneficial for bare-rooted trees to receive a ‘hard prune’ at planting. Potted trees also benefit to a lesser extent.

The branches and leaves of a tree are proportional to the roots. Whenever you prune it, you’re reducing its ability to feed its root mass, which then restricts itself accordingly. When you transplant a tree, its roots are being disturbed, and it’s best to reduce the leaf area correspondingly to keep it in balance.

If you don’t, when leaves start to grow in spring, there aren’t enough roots to sustain them. This drains the tree of energy, inhibits new growth, and weakens it, making it more susceptible to pests and disease. It will take time to rebalance itself and catch up.

It’s estimated you reduce a bare-rooted tree’s roots by about a third at planting time and a potted tree’s roots by approximately 10%, so that’s how much you should prune from its canopy.

How to prune for form

There’s no right or wrong options, but some forms are better for different situations.

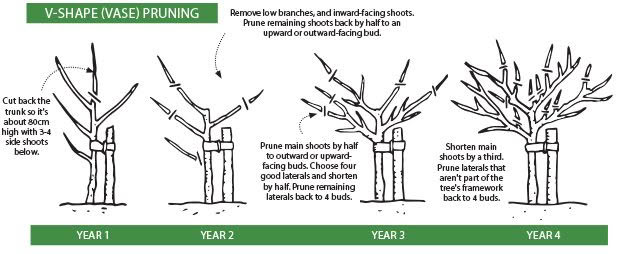

V-SHAPE

The commonly advocated choice is to take out the main or central leader and prune side branches to form an open, vase-like shape. In my opinion, it’s the best option if you want small, convenient-picking-height trees. They’ll produce less fruit than an A-shape, require annual feeding and pruning, but is it’s easier to harvest the fruit and takes up less space.

When form pruning, reducing size to create an easier-to-harvest V-shape is as simple – but painful – as cutting off the top third of your tree.

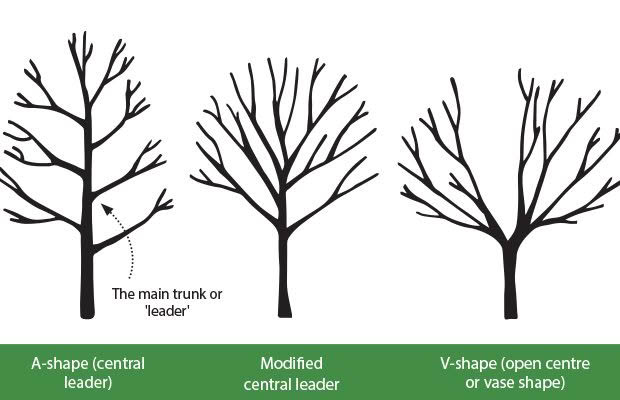

A-SHAPE

If you leave a tree to grow, it naturally sends up a central leader, and develops side branches in an A shape. If left to grow to its full height, it will form a large, easy-to-maintain tree with minimal annual pruning or feeding required and be very productive.

You can reduce its mass by eliminating low or crowded side branches.

Eventual height and width vary enormously depending on the variety and the rootstock but it’s usually 4-6m high. You’ll need a ladder to harvest it, and even then probably won’t get all the fruit (but the birds will thank you).

A modified central leader is commonly used on apple, pear, and cherry trees and is a compromise – it’s taller and stronger than a vase-shape but more open than an A-shape.

Pruning basics

Any pruning other than the 3Ds is for your convenience. You can prune ‘up’ from the base so you can walk under trees, or prune ‘down’ from the top to reach the fruit. It’s very difficult to have a tree that can fulfil both requirements.

You can also prune into topiary, shapes that grow along fences, or ones that go over arches.

There’s no right or wrong method, but pruning always has consequences:

• it reduces the leaf area (and therefore the root area the tree can support), and its ability to harvest sunlight (and uptake nutrients);

• it reduces the tree’s fruiting capacity.

A tree will direct a lot of its energy into replacing anything you remove, energy it could direct into fruit production or disease and pest immunity.

If you prune, help the tree by mulching it heavily with organic matter, so it gets extra nutrients to help it recover.

TIMING

This is important to prevent unwanted regrowth and diseases.

Always prune on a fine, dry day

Bacteria and fungi thrive in warm, moist conditions, floating around in the air looking for an open cut to infect.

Don’t prune in spring and autumn

A tree’s heaviest sap flows occur during the high growth periods of spring and autumn. Pruning causes the wounds to stay open longer, extending the time the tree is vulnerable to airborne disease.

If you do have to prune during these times, I’d recommend painting a sealant over the wound immediately.

Sheryn’s rule: Pick, then prune

This means summer fruit – peaches, nectarines, plums, apricots, etc – are pruned in mid-late summer. Autumn fruiting trees – apples, pears, quinces, feijoas, persimmons etc – are pruned in winter when the growth phase has passed.

If pruned in winter, summer fruit often sends up tall skinny regrowth called watershoots the following spring. This is because the tree has gone to sleep over autumn and winter, thinking it has big branches, pathways that it will direct a lot of energy into in spring.

Remove the branch or branches, and there’s nowhere for that energy to go, so the tree redirects it into new, long, green watershoots that need removing. Prune in summer and you save yourself (and the tree) the trouble.

THE EXCEPTION TO THE RULE

In New Zealand, the exception is citrus.

Reason 1 – lemon borer

This beetle can apparently smell a fresh prune from 2km away. It burrows into open wounds and infects the tree.

It only flies in warm weather. In Northland, this can be all year round; in more temperate climates, it’s September to March.

If you must prune during the borer beetle danger season, use a sealant or pruning paste.

Reason 2 – frosts

In colder climates, regrowth after pruning will be fresh and susceptible to frost.

In my South Waikato orchard, these limitations mean I can only prune citrus safely in winter when trees are laden with fruit. There is waste, but it means I do foil the borer beetle.

Should you ‘hard’ prune?

You may be able to stimulate a reluctant fruit tree to produce heavily by giving it a ‘hard’ prune, drastically reducing its size. When put under stress and ‘threatened’, it’s believed trees put all their energy into reproduction (fruiting). However, the loss of a large mass of leaves and branches weakens the tree long-term. It will sprout fast-growing branches, which will be weak in windy conditions and be more susceptible to diseases, pests, and other stressors such as droughts.

THE WOOD YOU WANT TO KEEP

Fruit trees fruit on branches of different ages. In most cases, removing younger branches will reduce fruit production.

Apples

Most apples, pears, and plums fruit on ‘old’ wood. Some apple varieties are tip bearing, or partial tip bearing, which means they fruit on the tips of branches instead of spurs on old growth. These include:

• Monty’s Surprise;

• Granny Smith;

• Peasgood Nonsuch;

• Bramleys;

• Gala.

Other fruit

Peaches, feijoas, figs, and the bulk of apricots fruit on wood that is two years old – that is, last year’s new growth (the fruit bud takes two years to develop).

Only figs (which also fruit on ‘old’ wood), persimmons, and tip-bearing apples fruit on new growth.

SHOULD YOU SEAL A WOUND?

Pruning paste or paint on a fresh cut isn’t usually necessary, and I prefer not to do it. The best way to avoid wound infections is to prune with clean tools in dry-hot or dry-cold conditions.

However, it can be worth sealing a wound if you have to prune in less-than-ideal conditions, such as during high sap flow, on a warm, moist day, or when lemon borer beetles are active.

Creating a seal over a cut stops disease and pests from entering through the fresh wood, but it won’t stop sap flowing.

A sealant is most effective if applied immediately – within seconds – of cutting. A paste that contains a fungicide ingredient is twice as effective as acrylic paint. An organic option based on trichoderma (a parasitic fungus that destroys ‘bad’ fungal spores) is another good option.

If you’re pruning in good conditions, using clean tools on a dry-hot or dry-cold day, a tree will send compounds to the area to protect itself, so sealing it isn’t necessary. Studies have shown that pruning paste and paint don’t improve on the plant’s natural response to an open wound in most cases.

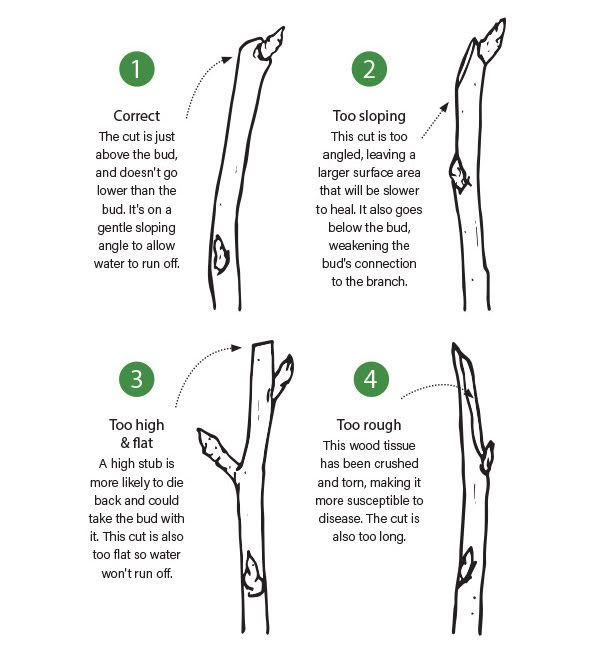

THE BEST AND WORST CUTS

The ideal cut protects the plant from disease, and encourages the bud to grow.

KEEP IT CLEAN

• Sterilise all equipment such as secateurs and saw blades between cuts, so you don’t spread disease around a tree or from tree to tree.

• Prune on hot, dry days for the best sanitary conditions. Most bacteria and fungal spores spread easily in a warm, moist environment.

• Minimise bleeding – don’t prune during high sap flows in spring and autumn.

The 3 Ds of year-round pruning

This pruning is done as soon as you notice diseased, damaged, or dead wood.

1. Disease

Judicious pruning can stop diseases from spreading. Simply cut off an infected branch or branches.

Cutting tools must be sterilised, before, during, and after the operation, or you’ll spread the disease with your blade to the next tree you prune. You can:

• dip blades in a bucket of bleach solution;

• wipe them with a rag soaked in methylated spirits;

• spray them with a steriliser or sanitiser.

It’s good to regularly sanitise equipment when pruning, but be especially pedantic if wood is diseased.

Prune back to clean, healthy wood. Remove and burn (or bag, seal and dispose of) all infected wood.

2. Damaged

Damaged bark is an entry portal for infection. Prune back to an easy-healing straight cut:

• where branches are rubbing on each other;

• if the bark is open and split.

The exception is if a branch splits due to too much fruit. If it’s still attached to the tree, I leave it to ripen the fruit, then prune it back after harvest. The risk of disease spreading is less in hot, dry, summer weather, and I’ve found the benefits usually outweigh the risks.

3. Dead

Trim back to healthy wood that can heal over, otherwise the tree is continually expending energy to fight against dieback.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.