The mystery of the lumpy lamb

The lump on Katie’s belly indicated something traumatic had occurred, such as a fall or hard hit from another animal.

A little lamb has a very big lump, and a mystery cause.

Words: Dr Sarah Clews, BVSc

Who: Katie, 10 week old, bottle-reared lamb

WARNING: Some images in this article may be graphic to some readers.

THE PROBLEM

Katie’s owners found her with a large lump on the side of her lower abdomen. When she arrived at the clinic, Katie seemed healthy apart from the lump and some minor wounds on her back legs.

THE INVESTIGATION

Katie’s vet used ultrasound to determine the cause of the lump. It showed a 20cm-long tear through the abdominal wall, a substantial wound in a young animal weighing just 12kg. The ‘lump’ was the intestines poking through it.

Katie had suffered a blow of such intense force that it had lacerated her abdominal muscles, causing a traumatic hernia. A hernia is a tear or hole in the body wall. Contents from the inside protrude out of the body, only held in by the skin. Common causes of a traumatic hernia include:

• a stroppy cow or goat using a horn to bunt the animal;

• a hard fall;

• hitting a blunt object at speed or with great force.

They’re also seen if a person uses improper techniques in an attempt to move a foetus around during labour. Cows in late pregnancy can also suffer a hernia when the weight of the calf causes the tendons under the belly to give way.

In this case, there was no obvious cause. We’ll never know what happened to poor Katie, but the huge hernia and the wounds on her legs suggested it was a major event.

THE TREATMENT

Traumatic hernias need immediate treatment. They’re very painful and cause a lot of stress to an animal. After a few days, the edges of the wound start to retract, forming scar tissue and adhesions, making it very difficult to repair. If veterinary care isn’t possible, humane euthanasia is the only other acceptable option.

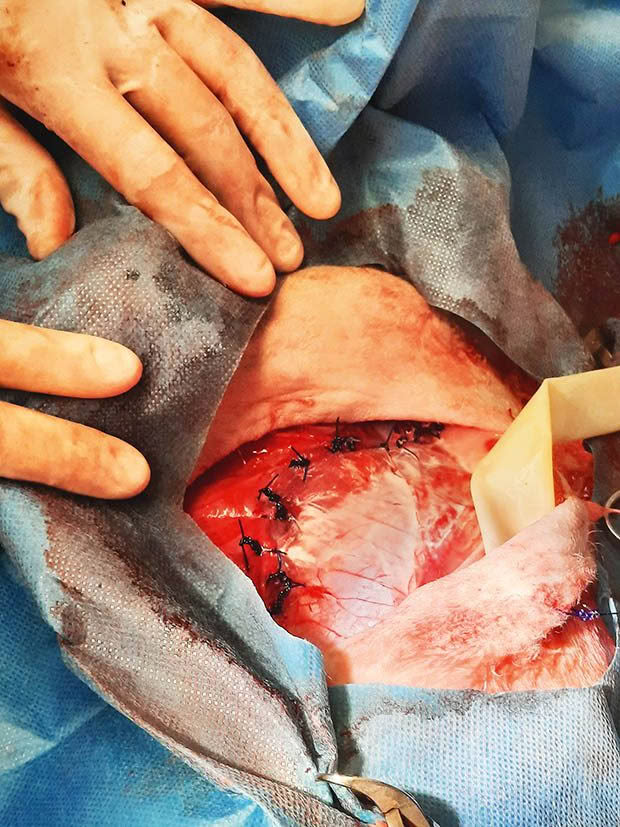

Katie had surgery to repair her hernia. Sometimes a tear in the abdominal wall can be short, but the lump can be quite large as the abdominal contents push out. Poor Katie had a significant gash, running almost half the length of her abdomen.

Because she was weaned, her rumen (the chamber of the stomach that processes grass and other feed) was well developed. It’s very heavy, so the greatest risk is the sutures breaking down under its weight. It took two of us to carefully stitch the hernia back together using a special technique that distributes tension evenly across the wound, holding it together

very tightly.

The repair left a lot of what vet’s call ‘dead space’ under the skin, because it’s no longer attached to the underlying connective tissue. The body responds by filling the space with a watery fluid (called a seroma). We put a drain in place so the fluid could run out, allowing the tissue to heal.

THE RESULT

Katie came through her surgery well. She received strong pain relief and stayed in hospital for monitoring.

The use of opioids can significantly slow the gut’s ability to process food, causing ‘bad’ bacteria to flourish, which can kill an animal. Katie stayed with us for two days until we knew she was passing stools.

She went home with a course of antibiotics, pain relief, and strict instructions for no ab-workouts (eg, to be kept in a small, flat paddock with no stress).

Five days later, she came back, and we removed her drain and checked the wound. It was a little inflamed and tender, but Katie was moving easily and seemed happy. On day 14, we removed her stitches and she rejoined the flock.

The site will always be weak, so Katie can’t be used for breeding. While her owners don’t intend to run her with a ram, another option for an animal in this situation is a contraceptive injection that covers the mating season each year.

3 THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT HERNIAS

• Hernias aren’t uncommon in grazing species. They’re normally only seen shortly after birth due to a genetic defect in the body wall, such as an umbilical hernia. Sometimes

a very small hernia will repair itself as an animal grows.

• Genetic hernias aren’t painful in the same way as a traumatic one like Katie’s. However, there’s a risk that if the intestine becomes trapped in the hole, it may strangulate, swell and cut off the blood supply. Animals can go into shock and die.

• Scrotal hernias are common in pigs, where intestines and fat follow the testicles as they descend into the scrotal sac.

5 RISKS OF A HERNIA REPAIR

Adult ruminants (sheep, goats, cattle, alpaca) face a lot more risks when under general anaesthesia compared to cats and dogs, including:

• bloat;

• regurgitation;

• loss of too much saliva.

Baby ruminants are spared these risks as they’re not eating grass but face others such as hypothermia and low blood sugar.

Thankfully, Katie fell between baby and adult, which worked in her favour. She received fluids spiked with sugar and was kept warm throughout her surgery.

The biggest challenge in this type of operation is keeping the metres of curling intestines on the inside during surgery. Ruminants produce a lot of gas. As you try to suture the wound closed, a massive amount of gas-filled intestines are trying to battle their way out onto the surgical table, making it a tricky and time-consuming procedure. Sometimes multiple assistants are needed to hold everything in place.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.