The Jellyologist: Meet the architecture graduate who found structure in jelly

A jolly delicious business born from an art project is reinventing a Kiwi classic.

Words: Emma Rawson Photos: Tessa Chrisp

Suppose there were such a thing as a jellyologist, a scientist with a degree in gelatin. Oh, the wonders they would see. Looking through a microscope, such a specialist might discover that there are joy particles in the molecular structure of gelatin.

They might hypothesize that this semi-solid matter creates a chemical reaction that makes kids and adults hoot with laughter at the sight of a wibbly-wobbly plateful. Or that jelly’s jiggly qualities have healing properties to soothe sore mouths after wisdom-tooth extraction or bring families together around a Christmas trifle.

Jessica Mentis does not have a degree in jelly; she has a master’s in architecture and a bachelor’s in spatial design. Still, she may rightfully call herself the Jellyologist, and she named her business just that.

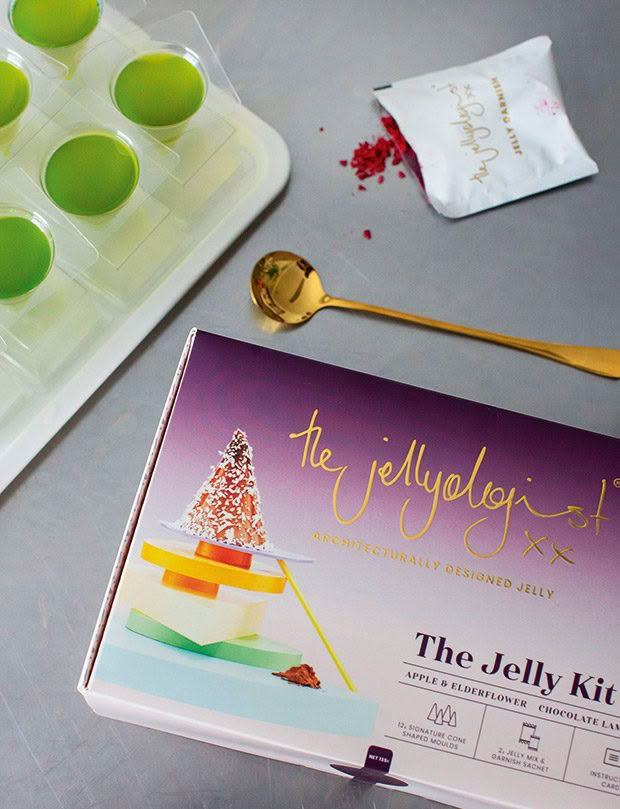

In the past five years, she’s studied the form, function and flavour of jellies and has made thousands of them in all shapes, colours and sizes. She’s also seen evidence of the magical spell that jelly casts on children making wobbly creations from her Jellyologist jelly kits, which are for sale in supermarkets.

“It’s a joy-inducing product,” she says. “Making jelly is an easy thing that brings happiness to children’s faces. That’s the part we love about it.” It all started as an art project. Jessica read a story in United States design magazine The Great Discontent about the #100dayproject, which called for creatives to post photos on Instagram of the same artistic project or series for 100 days.

Jessica had returned from living overseas in London and New York, where she had worked in marketing and as an assistant set designer. She was itching for something new, and the project allowed her creative juices to flow.

“I came across photos of old ornate jelly moulds in a book. They were carved from wood and set with copper. There was something architectural about them. Jelly is fun because gelatin itself doesn’t have a flavour, but it’s a conduit and takes on any flavour you give it.”

She poured her ideas into moulds she created using a 3D printer. Day one: a cherry liquorice jelly covered in silver balls. Day two: sour apple sherbet prisms. Day 10: marbled nectarine, plum and vanilla blancmange. Day 33: a strawberry and kiwifruit jelly castle. And, on the final day, raspberry jelly on marble spelling out the words “#100 days of jelly”.

“I wanted to test the limits of gelatin as a medium and see how I could manipulate its shape. The project was so much fun, but I had some disastrous moulds where I made the base of the jelly too narrow and it wouldn’t support the top. “There were shapes I created that would just go wobble, wobble, wobble and then fall over.”

Jessica Mentis didn’t imagine the artistic jellies she made for the #100dayproject five years ago would evolve into a business. She still owns the jelly moulds she used, including some vintage pieces and others she designed on a 3D printer.

Her 100-days project caught the attention of some famous New Zealanders, which led to her creating pretty pink jellies for fashion designer Trelise Cooper’s birthday party. Soon, Jessica was asked to make a Taj Mahal and Tower of London jelly for an ad campaign for Expedia. There was a growing demand for catering jellies for weddings.

“I’m an artist, and I don’t have a food background, so I had to learn the ins and outs of food preparation and commercial kitchens as I went,” says Jessica, who has another business venture creating art installations. “Transporting pre-made jellies across Auckland in the height of summer was a learning curve. I had some close calls where I had to have the air conditioner on full blast so the jellies wouldn’t melt.”

Jessica lives in an Auckland apartment, which has become Jellyologist HQ. She built a commercial kitchen so she can prepare hundreds of jellies at a time when catering for weddings and parties.

These days, she has the jelly catering business down to an inexact science. Sadly, the global pandemic put a halt to that side of the company. Thankfully, the Jellyologist consumer product had been launched in 2019 so when New Zealand went into level 4 lockdown in March, the Jellyologist make-at-home range of jellies was already in supermarkets.

During the first few weeks of lockdown, the jelly business looked like it was in serious trouble. “At first, we saw a drop off in supermarket sales because people were rightfully focusing on buying things such as pasta and rice. We were really worried about the business. But then we opened our online store and sales went gangbusters. “It was so unbelievably relieving and heartwarming when children started sending us videos of their wobbly jellies.”

The Jellyologist do-it-yourself range of jellies includes flavours such as Nan’s Pavlova, Packham Pear, Feijoa & Apple and Elderflower & Apple, which come with garnishes such as dried raspberries and white chocolate. Jessica created the flavours with food scientist and business partner, Jenita Evans. The gelatin itself is a byproduct of the beef industry, derived from collagen. Jellyologist flavours derive from New Zealand fruit juice, which is turned into a powder using a process called spray-drying. The technique creates an intense taste and a product low in sugar.

The master Jellologist kits contain the brand’s signature cone mould, a design Jessica had discovered during her 100-day project. “The cone is the ideal architectural shape for a jelly morsel. It has optimum wobble because the shape has a steep point at the top, which allows it to really wobble around on the plate. It’s also a self-supportive shape so it’s not going to implode or self-destruct.”

The Jellyologist has recently added new products to its range. All represent a healthier twist on the traditional New Zealand jelly, with 30 per cent less sugar than the market leaders and natural colours. “Jelly is so nostalgic, and we remember it from our childhoods, but there hasn’t been any innovation in this food category for 60 or 70 years. It’s been a long journey for us creating something innovative and healthy and still loads of fun.”

A JOLLY JELLY HISTORY

Sweet and savoury moulded jellies first made an appearance on the banquet tables of the noble families of Britain and Western Europe in the 1400s. Then, gelatin involved boiling bones and cartilage and was relatively hard to make, so jelly became a sign of status. The first recorded use of jelly in a trifle was in 1747 in The Art of Cookery by Hannah Glasse. Some 100 years later, the Victorians took jelly-making to greater heights, setting their creations in magnificent moulds.

In the 1930s, mass production meant jelly became cheaper and more readily available. In Depression-era United States, jelly became a way of eking out a meal, with lime jelly added as a side to savoury meals. In the 1950s, jellies and aspic-covered dishes had a revival, coinciding with the popularity of home refrigerators. The Jelly Tip ice cream was invented in New Zealand in 1951 and cost sixpence. In 1955, Bellamy’s fine-dining restaurant in The Beehive added Dominion Trifle au Sherry to its menu.

FOR JOY — OR HEALTH?

Some studies suggest that jelly could have health benefits. No, really. Following the same principles that have made bone broths popular in the fitness community, jelly contains protein and amino acids, which are building blocks for body tissue such as muscle. Ingesting this collagen derivative may keep skin plump, and gelatin may also help with gut health, lining the gut wall.

Medical studies have shown that consuming gelatin can relieve joint pain, although clinical trials have had mixed results. With all of these claims, further research is needed. “At the moment, we have no plans to enter that functional health space. Right now, our jellies are purely celebratory,” says Jessica.

WHAT EXACTLY IS GELATIN?

The old story about jelly coming from horse hooves is probably a myth and, if not, most certainly an outdated practice. While gelatin comes from the collagen of animal byproducts, such as bones and cartilage (and can be made from all sorts of animals including fish, cows and pigs), horse and cow hooves are made of keratin. Keratin is a different type of protein that can’t produce gelatin on its own.

Gelatin is a string of proteins and peptides (a short chain of amino acids). The proteins and peptides bond together in three-stranded helix structures (similar in looks to a DNA strand). When hot water is added to the gelatin, the helix shape unravels. As the liquid cools, the fibres reset with the water molecules trapped inside, creating its semi-solid form.

While there are some gelatin alternatives that are not made from animal products, such as agar, which is made from seaweed, Jessica is still looking for a vegan gelatin alternative to add to her range. She hasn’t found a vegan option that has the same transparency, texture, structural integrity and flavour clarity.

Recipe: Aperol Spritz Jelly

Serves 4

INGREDIENTS

500ml prosecco

25g sugar

¼ cup water

1 Jellyologist Classic Orange Jelly

⅓ cup aperol (an Italian bitter apéritif)

METHOD

Add 200ml of the prosecco, along with the water and sugar to a pan and heat until almost boiling. Open the jelly and sprinkle into the hot mix, stirring until dissolved.

Stir through the remaining 300ml prosecco and aperol. Pour into 4 serving glasses and refrigerate until set (about 4 hours).

Recipe: Raspberry, Ginger & Lime Trifle

This trifle, which has two layers of different flavoured jellies, can be assembled ahead of time and is a true Christmas-table showstopper. The ingredients are for a glass trifle dish about 150mm x 90mm but can be adjusted according to the size of the bowl.

Serves 10 to 12

INGREDIENTS

1 Jellyologist Raspberry & Tahitian Lime Jelly (with White Chocolate Garnish)

2 to 3 limes

1 Jellyologist Apple & Elderflower Jelly (with Freeze-Dried Raspberry Garnish)

1.5kg thick pre-made custard

150ml marsala, madeira or medium-sweet sherry

1.5 packets gingernuts

100g melted butter

2 packets large marshmallows

fresh strawberries

METHOD

Make the Raspberry & Tahitian Lime Jelly according to directions and pour into the dish. Let it set completely – four to six hours.

Slice the limes into 5mm rounds. In a jug, make the Apple & Elderflower Jelly and cool completely. Layer the lime rounds face up against the glass of the dish so they line all the way around, facing outward. Pour the elderflower jelly into the dish on top of the raspberry jelly and allow to set.

Pour the custard into a large mixing bowl and add 100ml of alcohol. Stir to combine. Place gingernuts, butter and remaining 50ml of spirits into a blender and blitz to a crumb.

To assemble, alternate layers of custard, marshmallows and the rough-crumb gingernut mixture, finishing with custard. Decorate with remaining marshmallows, strawberries, sliced limes and garnishes.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.