The fast brain / slow brain split and healthy decision making

The brain is often split when it comes to processing information, which could be why humans don’t always do what they know they should.

Words: Rosemarie White

“I know what I should do – I just don’t know why I don’t do it.” It’s the most significant issue in healthcare. “Why don’t I take my medication?” “Why am I eating junk food?” “I’ve paid for a gym subscription. Why don’t I go?”

We all know what we should be doing – eating consciously and healthily, exercising regularly, not smoking, cutting back on alcohol, meditating, attending to our dental health, keeping our weight down, taking any medication and maintaining a positive mental outlook. So why aren’t we doing all this? Our goals to be fit, active, and free from pain and chronic health conditions are admirable, but our lack of action is bewildering.

Nobel Prize-winner Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking Fast and Slow, explains the gap between what people know they should do and what they actually do. The author describes how the brain’s two systems work. System 1 is the fast, automatic, reptilian part; system 2 is slow and methodical. Think of system 1 as the “fast brain” and system 2 as the “slow brain”. The fast brain roughly equates to the unconscious mind and drives 95 per cent of behaviour. Heuristics, or mental shortcuts, are the thoughtless, energy-efficient routines that help you save your strength for the difficult questions.

That’s where the slow brain comes in. It takes care of the conscious, painful, time-consuming processes. As clever as the slow brain can be, research shows that the fast brain easily dominates it. Our slow brain has only so much capacity and when it’s distracted – with tasks, stress, or lack of sleep – the fast brain takes over. And, generally, the fast brain is not good news for healthy intentions. Think of it as the teenager behind the wheel.

The answer to the question of why we don’t do what we know we should lies in the fast-brain/slow-brain “gap”, the time slot between our ideal behaviour (slow brain) and the mindless habit reversal (most of the time, the fast brain). Alas, our capacity for self-delusion is infinite, especially when it comes to making excuses for lack of progress.

Despite our good intentions, the fast brain still runs the show. The second the slow-brain attention is diverted by tasks requiring mental concentration, the fast brain falls back into old practices. When possible, the brain makes a behaviour into a habit which saves effort and provides more capacity to deal with complex matters. Habits mean we aren’t always making decisions, weighing choices or prodding ourselves to begin. Life becomes simpler. About 40 per cent of our behaviour is repeated almost daily and in the same context, research suggests. So how do we form habits that serve us well, not add to our ill health?

8 go-to healthy habits

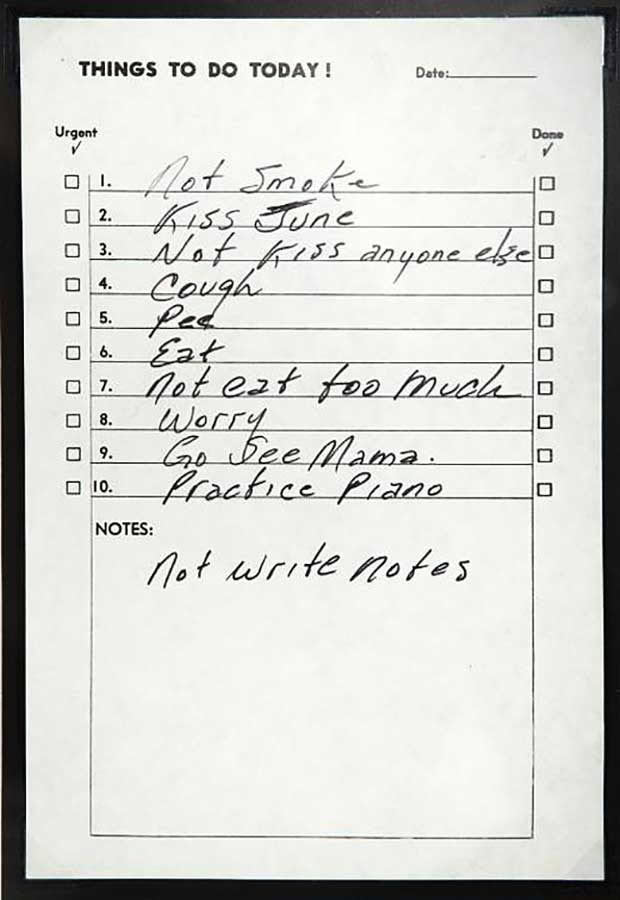

1. Make a list

If you find the idea of making a list discouraging, then perhaps you might like to consider Johnny Cash’s list above.

2. Start small

Decide on a very small habit. Make it so easy you can’t say no. “I’ll just walk for five minutes every day.” Or “I’ll do five push-ups per day.” Once you have started moving, it’s easy to carry on. Small, incremental steps are the best way to move towards your goals.

3. Set routine

By making certain daily activities into fast-brain routine, we save our slow-brain energy for decisions and willpower that are in limited daily supply. “I’ll keep some healthy food in the fridge.” Success is a few simple disciplines, practised every day, while failure is simply a few errors in judgement, repeated every day.

4. Track triggers

We ignore the slow-brain reminders and triggers we set for ourselves as our slow, conscious brain filters out monotony so it can spend its time on more pressing matters. This slow-brain “trigger blindness” turns control over to the fast brain, which has its own set of self-triggers for immediate gratification and well-being. Track your own progress. Write it down. Ask yourself what helped you succeed versus what might have caused you to go off track. You’ll notice patterns of behaviour and what needs to be in place for you to stay on the healthy path.

5. Stick with it

Getting healthy takes planning, effort and, above all, patience. When people set out to improve their health, they often think about action. Eat better, meditate, exercise more… But getting healthy actually starts in your head. The key isn’t having a taste of your ideal self for a few weeks then reverting back to old ways. It’s about creating sustainable change. Consider behaviours you can adopt that are more likely to stick.

6. Motivate yourself

Don’t rely on your motivation; be accountable to yourself. People work harder when they feel accountable to someone and there is a no more powerful accountability partner than yourself. Rather than relying only on others, set up a system whereby you regularly track your own progress. Ask yourself what helped you succeed versus what might have caused you to go off track. Reward yourself when things go well but don’t beat yourself up when they don’t.

7. Simplify the options

There’s a bewildering variety of research on self-control with surprisingly different conclusions, but one idea is well-supported by studies. Researchers found that making repeated choices depleted the mental energy of their subjects, even if those choices were mundane and relatively minor. According to the Harvard Business Review, if you want to maintain long-term discipline, it’s best to “identify the aspects of your life that you consider mundane — and then ‘routinize’ those aspects as much as possible. In short, make fewer decisions.”

For lasting change, the steps you take must ultimately change your environment and schedule. The running gear is always in the same spot, ready to go; exercise every day not just some days; stop buying snacks if you want to stop snacking (no willpower needed); pack a very similar lunch every day of the week; and embrace the power of routine to get the necessary done. Don’t fritter away your will power on small stuff.

8. The 15-Minute Pause

When temptation is too great — those little cupcakes are winking at you from across the table — decide to wait 15 minutes before caving in and eating one (or two). It works amazingly well. Framing choices positively also helps more than you might expect: “I choose not to eat for 15 minutes.”

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.