The curious structure of the honeybee world

Just as in different human societies, a honeybee colony has its own structures, systems and ways of living.

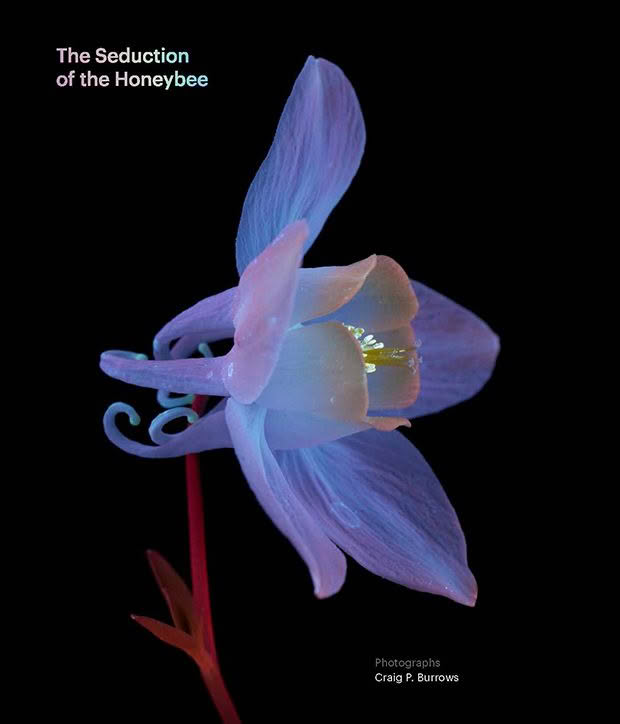

Words: Extracted from The Seduction of the Honeybee by Craig P. Burrows

Apiculture manager and experienced beekeeper Brian McCall, suggests that if you were to compare a honeybee colony to a model of human society, it would represent communism in its purest form: ‘There are no individuals, there is only the colony and its survival. Everything is for the benefit of the colony, and everybody has a role to play. That’s why they’ve lasted so long. The whole purpose of a hive is longevity — it’s about constantly keeping a genetic line going as long as it can, constantly producing the next wave of bees to support itself.’

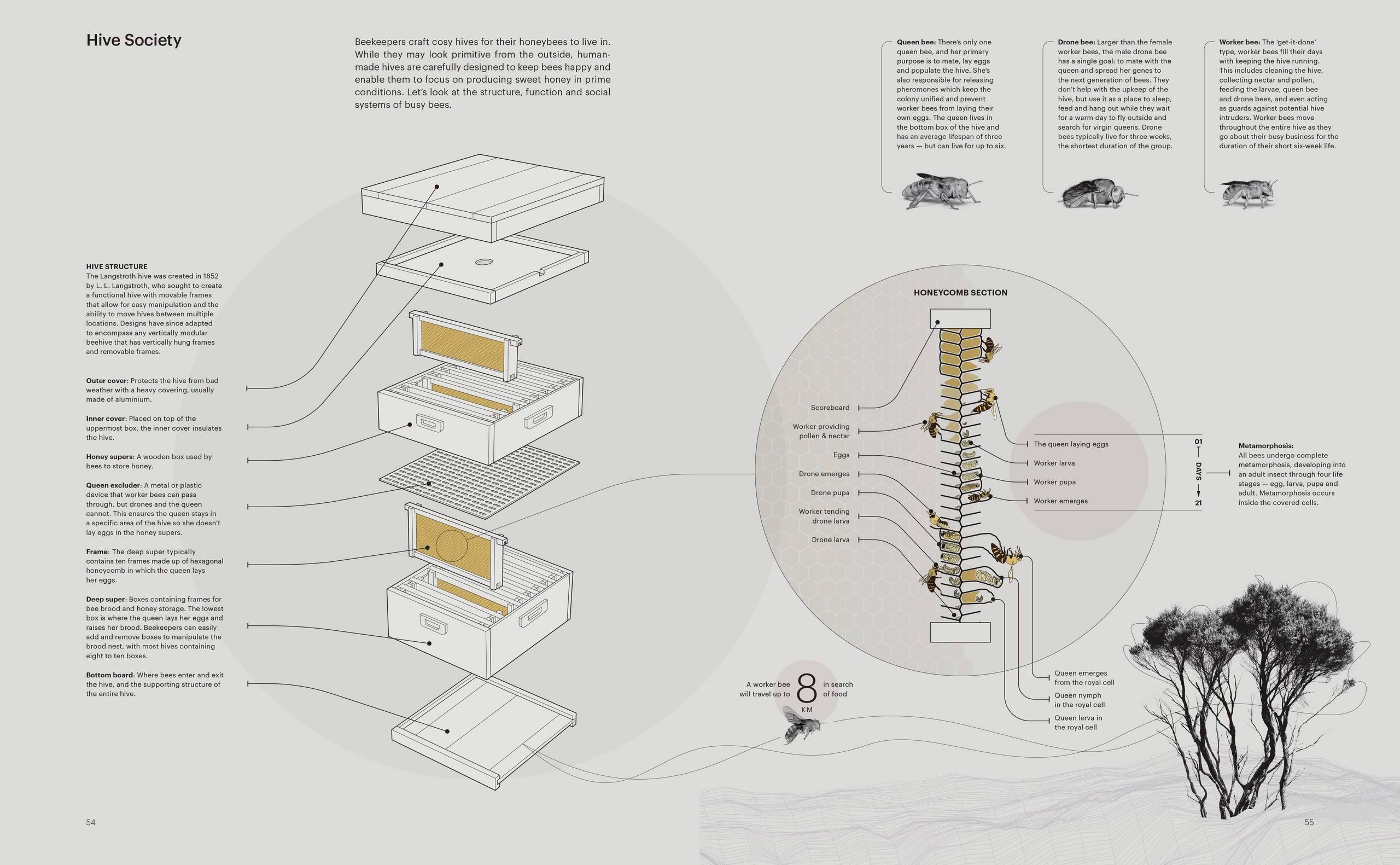

To fulfil that purpose, there’s a strict hierarchy of position in a honeybee colony with a built-in structure around the role of each type of bee — the queen bee, worker bees and drones.

There is, of course, only one queen bee. The remaining bees — there could be up to 60,000 in the peak of the season — consist of approximately 5 per cent male drone bees, and the female worker bees that make up the vast majority of the honeybee population.

THINK YOU’D LIKE TO BE THE QUEEN BEE? IT’S NOT ALL IT’S CRACKED UP TO BE

It’s a regal title and, sure, you have worker bees attending to your every need, feeding you, grooming you, clearing your waste. But a queen bee’s ultimate purpose is to mate and lay eggs in order to populate the hive — she’s a super mum on steroids. And life as a breeding machine sounds, well, relentless.

The queen bee’s life begins as a fertilized egg — and technically any fertilized egg has the potential to become a queen bee. Once the eggs hatch into larvae, the potential queens are selected by the worker bees, who then feed the queen bee larvae a diet consisting exclusively of royal jelly. Royal jelly is a secretion from the hypopharyngeal glands of worker bees that is rich in protein and vitamins. While every larva is fed royal jelly for the first three days, only the queen bee larvae are fed it beyond that. This royal diet allows them to become sexually mature — the only females in the hive to get to this stage.

The queen bee larvae go into the pupa stage where they go through metamorphosis to become bees. Queen bees are identified by a longer abdomen than that of the drone and worker bees.

The newly hatched queen bees will stay in the hive for about a week for their wings to harden sufficiently to be able to fly. During this time, the virgin queens fight to the death, as there can only be one queen in a colony at a time. Queen bees have stingers that aren’t barbed, allowing them to sting multiple times without dying.

The victorious virgin bee then heads out to mate with male bees, the drones.

In order to avoid inbreeding, the virgin will travel up to a mile (one and a half kilometres) away to mate with drones from another hive. When she mates with a drone, in mid-air, the drone’s endophallus (the bee equivalent of a penis) will break off inside her and the ejaculate will go into the queen’s spermatheca to be stored.

As the queen bee mates with maybe ten to fifteen drones at a time, she ends up with several endophalli inside her. These will either fall out, or the worker bees will clean her out back at the hive.

The queen bee will return to the hive to lay eggs. She might continue this pattern for several days until she reaches capacity in terms of the amount of sperm stored in her spermatheca. There are two types of eggs laid by a queen bee. The eggs that remain unfertilized become male bees, the drones. The eggs that are to become worker bees are fertilized by the queen by spraying them with the spermathecastored sperm as she lays them.

At the height of the season the queen is working hard, laying up to 1,500 eggs every day. This is in order to build up the population in the hive to coincide with the peak time for nectar flow in plants local to the hive. Once the nectar flow kicks in, the queen bee will lay fewer eggs. She knows that the hive won’t need a massive population forever once it has capitalized on the nectar flow. Towards the end of the season her production is decreasing even more, down to about 500 eggs per day.

A queen bee has a much longer life cycle than other bees. Assuming she’s mating well, in cooler climates like Canada, where a season lasts for about six months, you might have a queen bee that can be around for up to six years. However, warmer climates such as the Mediterranean or New Zealand will have a ten-month season, so if you can get two years from a queen you’re doing well.

In comparison to the lifespan of worker bees — about six weeks in the summer — it’s a huge difference, up to forty times the lifespan. To put it in human terms, it would be like certain humans had a life expectancy of 3,000 years compared to the measly seventy-three years that is currently the average life expectancy worldwide.

What demarcates a queen bee from her worker bees is that her diet consists solely of royal jelly, so in regard to the age-old pursuit of longevity, it seems the queen bee could be on to something.

If a queen bee is losing the ability to lay effectively as she ages, a beekeeper will often replace her for the good of the hive. In nature, the worker bees will step in and kill her and anoint her replacement. The queen might hold the regal title, but ultimately the power lies with the proletariat.

WORKER BEES: GOING BEYOND THE NINE-TO-FIVE FOR THE GOOD OF THE HIVE

The worker bees perform every role necessary for the running of the hive. From the moment they hatch, they start to work. As well as foraging for nectar and pollen for the hive, they are also tasked with making and processing wax, honey, royal jelly and propolis; building and cleaning the cells that the queen bee lays eggs into; feeding the larvae, queen and drones; taking care of the queen; scouting; and acting as guard bees.

There are three stages in a worker bee’s life and each stage is roughly twenty-one days. It takes twenty-one days from when the queen lays a fertilized egg for it to go through the larva stage until the bee emerges from the pupa. During that time, older worker bees care for the queen bee, her newly laid eggs and emerging larvae.

When the worker bees emerge they are tasked with feeding the next round of larvae with royal jelly from their hypopharyngeal glands. These glands atrophy as they mature and are instead used to ensure honey quality by using them to secrete the enzymes invertase, diastase and glucose oxidase into honey.

After twenty-one days of being the hive housewives, the older bees are sent out into the field to forage for nectar and pollen. In performing that duty, again for approximately twenty-one days, they can be working for ten-plus hours a day, over a distance of many kilometres. They continue this high rate of work until their wings disintegrate and they die off — they literally work to death.

It’s a tough workload for a relatively short lifespan, but some worker bees do get to live longer over winter. When the flowers become scarce as the temperatures drop, a hive shuts down production for six months or so, and the worker bees can survive for that amount of time.

But there’s no cosy hibernation going on — unless you’re the queen. The worker bees have built up their fat stores and, as it gets colder, cluster together in a balllike formation and generate heat by vibrating their wings. The queen is situated in the core of the ball and that’s where the heat is concentrated. As the worker bees on the outside of the ball get colder, the bee ball will fold in on itself, ensuring that the colder bees on the outside are moved in towards the middle where they can warm up. The ball will move around the hive to where they’ve stored honey and that heat from the quickly vibrating wings will liquify the honey, so they can access it easily to use for energy.

As it gets colder and colder, the ball gets tighter so nothing can get in, not even oxygen, making it naturally high in carbon dioxide. This extra carbon dioxide slows down their metabolism so they don’t need to consume as much. Then, when spring has sprung, it’s back to work for these hardy and hard-working honeybees.

WHEN YOU’RE A DRONE, A DALLIANCE MEANS DEATH

The male drone bees have a bigger body, wings and eyes than worker bees and the queen. They’re only present in a hive for part of the season and they’re there for one purpose only — to carry on and spread the genetic code of the queen bee.

On suitable days during the season, the drones will fly out to a congregation area, usually about 1,000 to 1,700 feet (300 to 500 metres) from the hive. A virgin bee flies into the drone congregation, mating with as many drone bees as she can.

This happens in mid-air at heights of anything from three feet (one metre) off the ground to half a mile (one kilometre) in the air.

A LIFE’S WORK

In a honeybee’s lifetime, it will produce just 1/12th of a teaspoon of honey. It takes more than 500 bees to collect just one pound (450 g) of honey, and they fly up to 50,000 miles (80,000 km) and visit around 2 million flowers to do it.

The drone bee dies after mating, and if he isn’t able to successfully mate, the worker bees that are designated as hive guards will wait at the entrance. When the unsuccessful drone returns home after a long day of waiting around, those guard bees will kill him and throw him out of the hive because he’s a drain on resources and detrimental to the longevity of the hive.

Extracted from The Seduction of the Honeybee by Craig P. Burrows, published by Blackwell & Ruth.