Christchurch artist starts new Italian life at 57

- Averil and Bruce enjoy having breakfast overlooking their lush garden where fruit trees are laden during summer.

- Italians call Averil “Eva”, which she has adopted as the name of her Italian house and gallery.

- The 200-year-old stone house took two years to renovate and decorate to the couple’s taste.

- The iron trellis above the bed that Averil insisted on having erected in case of earthquakes.

- Each room is a gallery for Averil’s art and the collectibles she has found on her travels through Italy.

- Averil takes her shopping basket to stock up on vegetables, but she is also on the lookout for fabric.

- The snow-capped tips of the Apennies are a splendid backdrop to the bustling market in Piazza Garibaldi, one of the biggest town squares in Italy.

- Introdaqua, the hillside town Averil fell in love with, still has the remains of a medieval castle.

- The Abruzzo region is a bountiful provider of fresh produce, cheeses and cured meats.

- The tiny town of Introdaqua is a maze of ancient cobbled streets and sturdy grey stone buildings, brightened by colourful seats and baskets of hanging flowers.

- Many of the locals are elderly and enjoy sitting outside and watching the world go by especially during the evening when people parade through town in their finery.

- When townsfolk are eating and resting, the streets are quiet enough for little cyclists to try their skills

Christchurch’s Averil Stuart-Head followed her heart to create art in a medieval village in Italy.

Words: Venetia Sherson Photos: Nicola Edmonds

When an email popped into Averil Stuart-Head’s inbox eight years ago inviting her to take part in the illustrious Florence Biennale of Arts, she assumed it was a Nigerian scam and binned it. At the time she was the less-than-contented owner of a shabby-chic gift shop in Christchurch. “I thought the business was a good idea. But it wasn’t for me. So it went on the market.”

A second email arrived six weeks later. This time she took notice, checked out the credentials, took a deep breath and thought, why not? She cloistered herself in Takaka, completed three pieces of textile art, and flew to Michelangelo’s hometown where life is as intoxicating as the chilled prosecco.

A converted wine cellar makes a perfect studio for Averil, who can spend up to 12 hours a day working on her art surrounded by trunks of fabric treasures unearthed from attics, street markets and second-hand shops in Italy and New Zealand.

The experience was potent. Like artists over the centuries, the self-effacing but entrepreneurial Kiwi, who was raised in Westport and owned her first business in Levin when she was 19, fell in love with Italy and looked for “for sale” signs. Within a week she had signed off on a 200-year-old stone house in Introdacqua, a medieval village in the province of Abruzzo, two hours east of Rome. It was sunny, with a garden, relatively flat land, views of the Apennine Mountains and a long-disused wine cellar. Ah, she thought. My workspace. And so, aged 57, her other life began.

The flower-clad balcony off the bedroom is a place to watch the tapestry of life unfold in the Italian village where she lives for months each year.

The path from Christchurch gift-shop owner to artist in Italy sounds romantic. But the evolution took time and there were several side roads. In New Zealand, Averil had previously owned a range of businesses including a rest home, restaurant and a sheepskin-coat manufacturing company that produced garments for tourists and the export market. She and husband Bruce Head also renovated their own houses, including the one in which they were married.

While she had been a quilt-maker and embroiderer since her mid-30s, she had never considered herself an artist. But when she sold the sheepskin-coat business her crafting took on sharper focus. She particularly became interested in the colourful and intricate Amish quilts and the Amish way of life. When she and Bruce moved to Staveley, near Mt Hutt, they built a big red Amish-style barn, where they hosted quilters’ gatherings.

At the Sulmona market you can buy anything from garlic to silk scarves.

Courage is the natural bedfellow of creativity. And Averil has never lacked boldness. “When you step out of your comfort zone and follow your heart, you never know where it might lead.” Her favourite auntie was only 55 when she died, which partly motivated Averil’s move to Italy. “Bruce and I live by the rocking-chair test. That means we don’t want to be sitting in our rocking chairs in our old age saying, I wonder what would have happened if we’d bought a house in Italy, for instance….”

When she phoned Bruce to say she had found a house in Introdacqua, he said let’s do it. She says he is her biggest fan and supports her choice to live in Italy for part of the year. He’s a builder in Christchurch and busy with the rebuild, but he joins her in Introdacqua for two months each year, weighed down with trunks of fabric treasures bought under Averil’s instruction.

Averil returns to New Zealand when the autumn chill settles in the valley surrounding her Italian home. She says her art reflects the place where she is living. In New Zealand, she makes felt art and home décor pieces from merino, rare-breed sheep, alpaca and the curly locks of angora goat. She and Bruce prowl around the farms of local breeders who produce some of the finest fibre in the world. Post-earthquake, she finds it soothing working with natural products. Ironically, the Abruzzo region also had a severe earthquake in 2009. As a result, her four-poster bed in Introdacqua has a specially designed iron trellis above it, in case the roof caves in.

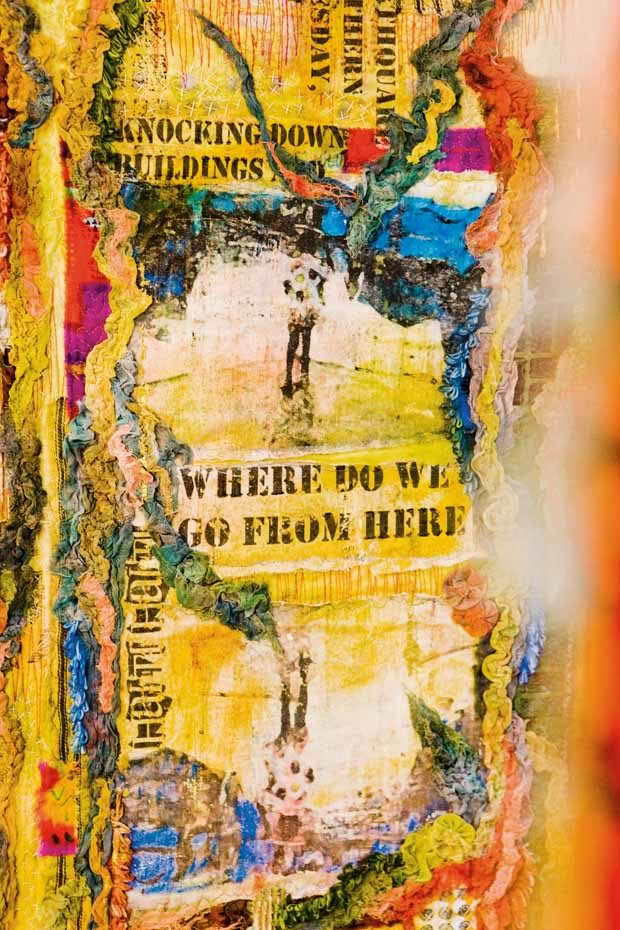

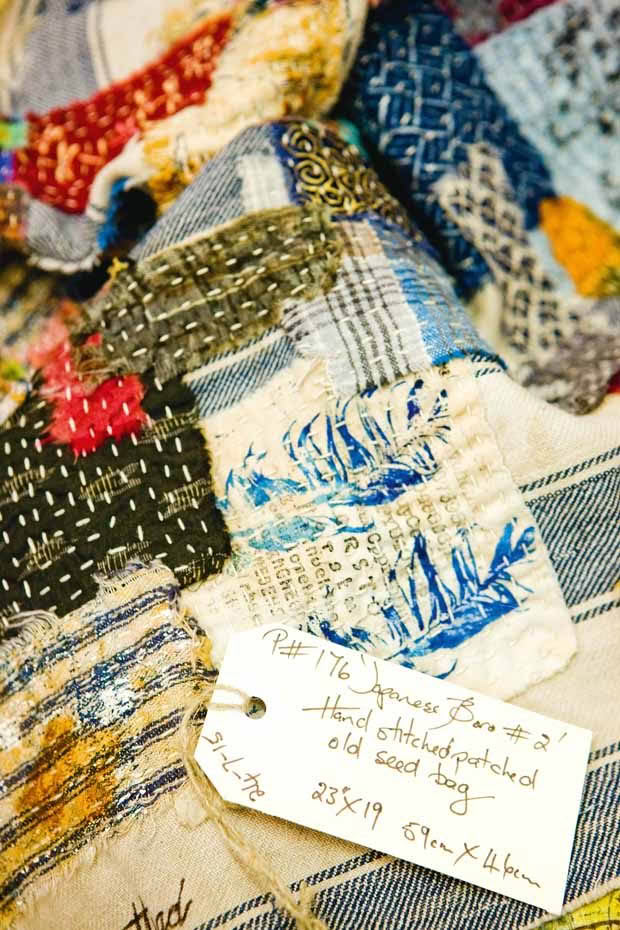

Art work by Averil Stuart-Head.

In Italy, her work is lighter and brighter, reflecting the warmer light and vibrancy of Italian life. The converted wine cellar, which doubles as a gallery and workspace, has been transformed into an Aladdin’s Cave of fabrics, tools, paints and finished art. Some pieces have travelled to exhibitions in the United States and Europe. One, a haunting piece called Where Do We Go from Here? was prompted by a photo of a young Haitian girl; another, inspired by Anzacs, is a vivid splash of scarlet poppies.

She finds materials in unlikely places. Old millers’ flour bags destined to be thrown out are cut up and recycled. Rags and pieces of dyed cotton are sewn into Japanese ‘boro’, traditionally worn by peasants and passed down through generations.

Italian markets are a particularly rich source of treasures. At the twice-weekly market at Piazza Garibaldi in nearby Sulmona, she looks for second-hand linen and old crocheted doilies, which she paints or dyes to add as texture in her work. Heirloom pieces in pristine condition are kept. They may be fine linen cloths with initials stitched on, or boast hand-crocheted edges. Scarf stalls are a sumptuous source of old silk, which she tears up to add to her work. A most precious item revealed itself during her Italian house renovations.

“It was a large scrap of silk from a scarf that was used to tie something together.” She carefully unravelled it to find a fragile and frayed cloth of faded pinks, reds and pale blues. The fabric was added to another precious fragment saved from her grandmother’s house in Westport and became part of the series, Remnants from the Past.

Telling stories through her art is important. Memoir and narrative are woven through layers of fabric and paint. One piece features her elderly Italian neighbours, Delio and Maria, tending their vegetable garden. Delio, a former POW in Australia, died two years ago aged 92 but Maria still works in the garden. The couple features in a series of work titled, Capturing the Essence of Italy. Averil says the rhythm and pace of Italian life grounds her.

“I can walk to the bank, the post office, the butcher, the baker and the cafe/bar. I love that the shops close at 1pm for three hours. There’s a quiet calm in the knowledge that you, like most Italians, are sitting down for a lunch of pizza and pasta. I love seeing the brass bands parading around the streets on summer weekends, and the evening passeggiata when people stroll in the piazzas and main streets in their best clothes.”

She says living in Italy emphasizes the importance of being happy with what you have. “The people here don’t have as many choices as we do.” She likes the simple life, the solitude and space to work. Most days, she will spend up to 12 hours in her studio. “I think there comes a point when we need to go beyond being a mother, daughter, sister, wife, grandmother, aunt, friend, secretary, nurse or whatever, to follow your own course, to do what makes your heart sing, not to mind so much what other people may think. I’d like to encourage those who want do something creative, something they can become lost in, to go and look for it.”

She quotes Robert Redford’s line from Out of Africa: “I don’t want to get to the end of my life… and find that I’m at the end of someone else’s.” She once light-heartedly suggested to Bruce that he engrave on her headstone, “She had a go.” She adds: “He’ll most probably put, ‘She had to go.’ But, he loves me, really.”

THE SIMPLE LIFE

The promise of la dolce vita has drawn many foreigners to live in Italy. Images of gnarly olive trees, grape-heavy vines, a language that sounds like poetry, long lunches and sun-soaked terraces are as seductive as a siren. Averil remains entranced eight years after she bought her house in Introdacqua. But, she says, it was no easy ride. First the house. She and Bruce had restored houses in New Zealand. Bruce is a builder. But their 200-year-old home in Introdaqua has stone walls 60cm thick. It took jackhammers and large concrete drills to power through the rock and plaster. It also took 18 months. “The house wasn’t a ruin, but it did need a lot of work to bring it back to life.”

Then there is what Italians call Il Sistema or The System (caps intended). Anyone who has lived and worked in Italy knows about the administration, paperwork, bizarre laws and red tape. Averil says Italians are the first to shrug their shoulders, roll their eyes and ask: Mamma mia, what can we do? While she now speaks and understands enough Italian to get herself out of a hole, she has had to call on English-speaking Italian contacts to help. Long queues at post offices and banks are a way of life.

“You need to be patient. But that’s not a bad thing. It always ends with many ciaos and handshakes.” She says, in Italy, she sometimes feels isolated; she misses Bruce when he is not there and they Skype daily. “But you have to weigh these things against the experience, which is what coming here was all about.” Any downside is balanced by the pleasures of making Italian friends, focusing on her art, eating fresh organic produce and just being. In Italy, she is called Eva (pronounced Ava), because Averil is a hard name for Italians to say. The simplification seems to sum up her Italian life: la vita semplice.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.