Sister Mary Horn of Teschemakers Dominican convent finds her third calling

From the moment she was baptised Mary Dominica, Mary Horn was on a path to a convent. Her call to be an artist came much later — at nearly 60.

Words: Nathalie Brown Photos: Brian High

To refashion Shakespeare’s As You Like It, the world’s a stage; life just a series of interconnected acts. Mary Horn, whose time on earth has been influenced by many a poet, has so far performed three of those acts: teacher, religious sister and painter, each calling approached with love. At 17, one of seven children from a devout Catholic family in Waimate, South Canterbury, she was accepted into teachers’ college, starting as a probationary assistant at an Invercargill state school a couple of years later.

Teaching was her first calling. Her second, in 1958, came on entering a Dominican convent. “I was 20 and literally in love with God just as the other girls I knew were in love with the boys they would eventually marry,” she says.

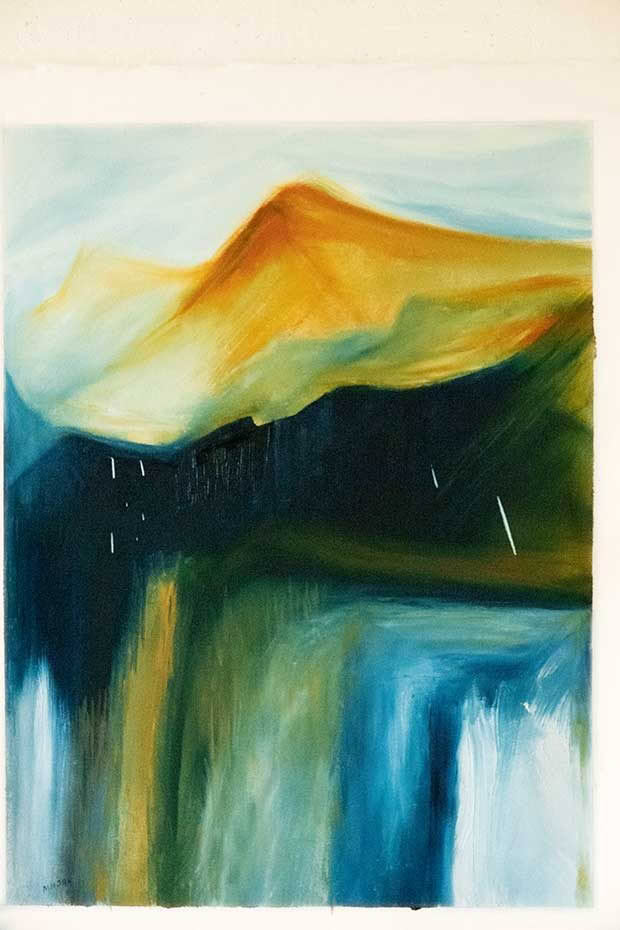

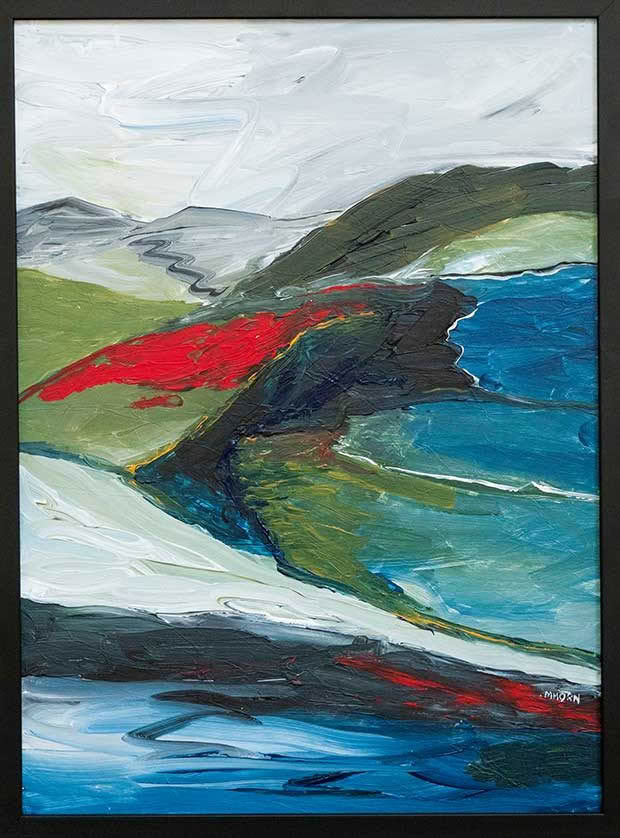

Pictured is Rockface (oil on canvas).

“The search for God is a love story. The God of my understanding is always elusive, always changing. So I’m on what I call the God quest. I’m still on it at 80. The young women I knew in the 1950s have a very different love for their husbands now than they had as young brides. It’s a similar thing for me.”

After her novitiate in Dunedin, she lived in convents from Auckland to Invercargill, working in Catholic primary schools and observing the daily 16-hour prayer cycles and routines of a teaching sister.

“When I went into the novitiate, there were 22 young women and we had a lot of fun together. There was a recreation period every night when we played tennis and netball — we tucked up our habits in a particular way known as kirtling, pinning them at the back.

Photographer Brian High’s portrait of Mary was taken in front of one of her paintings in the gallery, Crafted, in Oamaru’s Harbour Street.

“We sang, made up dances, put on little acts for each other. Or we’d sit around talking and doing beautiful embroidery. We made life-long friends there.” But eventually, she says, young women no longer wanted to become sisters.

“It happened gradually between the 1980s and 1990s, and it was like watching something you love slowly dying.” Over time, the Dominican order sold off most of its convents, the sisters happily moving out of institutional life and into the wider community where some lived together in smaller houses and others lived alone.

In the early 1990s Mary, who had been sharing a home with four others, moved to the sizeable Dominican convent Teschemakers, near Oamaru.

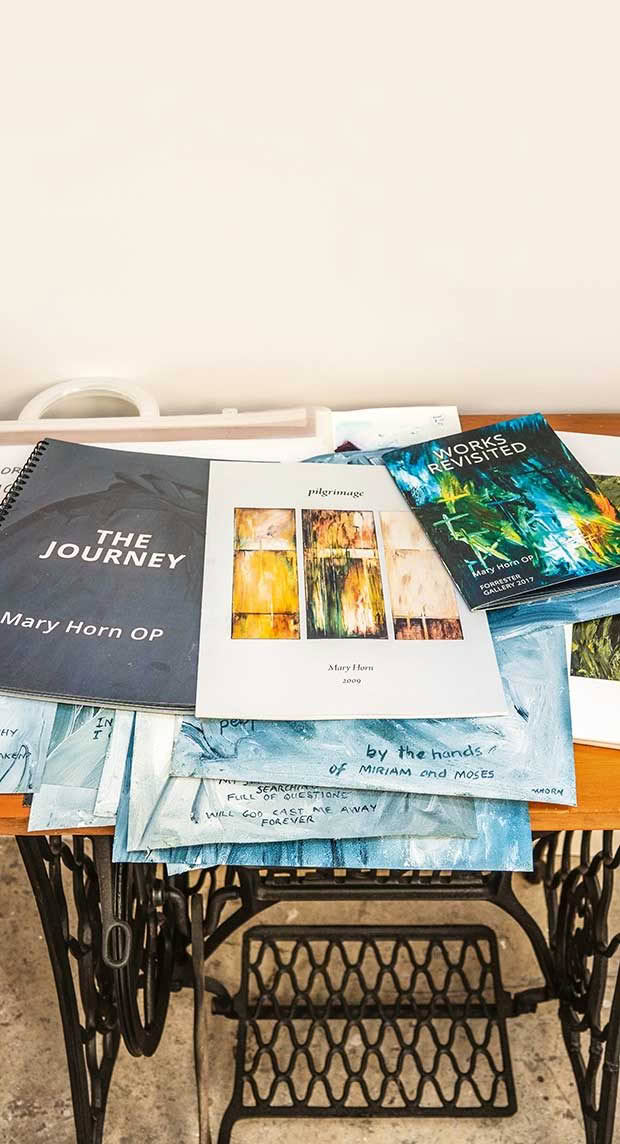

Mary has produced seven slender volumes of reproductions and reflections. They are available at the Crafted gallery and from maryhorn37@gmail.com.

Teschemakers, once home to 140 boarding girls, had closed as a school in 1978, mainly because there weren’t enough sisters to teach and manage. In 1980, it became a conference and retreat centre.

Mary worked there from 1990 to 2000 when the property was sold and its new owner gifted her a house and studio in the grounds, in perpetuity. During that time came the third act.

While Mary remains a Dominican sister and is active in her congregation, running monthly scripture classes and keeping in close contact with pupils at nearby co-educational St Kevin’s College, Mary accepted her third call – painting – at 57.

The Kakanui Mountains, seen from Teschemakers Road close to Mary’s home, are a strong influence on her paintings.

“A call is something you are passionate about and must do. It chooses you; you don’t choose it,” she says.

“You don’t have a choice. And if you don’t do it, you have lost something.

“Several aunts, my grandparents, several nieces and nephews have painted – some more seriously than others. There’s a significant emphasis on art among the Dominicans. The Early Renaissance painter Fra Angelico was a Dominican. His inspiring 15th-century works include such masterpieces as the Annunciation, the San Marco Altarpiece, and the Adoration of the Magi.

“I was also influenced by Colin McCahon’s work, which is part-symbolism, part-realism, part-abstract. I was drawn to the German expressionists, too.

“Then I discovered my true self-expression in abstract painting. I just tried it, and it was as if I had come home. I found where I belonged.”

Our Lady of the Rosary Chapel stands in the grounds of the former Teschemakers boarding school and Dominican convent, a gentle stroll away from Mary’s front door.

Many of her earlier paintings included verses written by poets: some 13th- and 14th-century Dominican mystics and others such as Gerard Manley Hopkins (a Victorian poet and Jesuit priest), T. S. Eliot (the American/English 20th-century poet and literary heavyweight) and New Zealand poets James K. Baxter and Allen Curnow.

“All the poets I’m influenced by – including the New Zealanders – speak about the mystery of life. And you can only speak about that mystery through art, poetry, music. All of these, when well-wrought, are an exploration of that mystery.” She still observes a vow of poverty, she says, and doesn’t earn any money from her work.

“It goes into our congregation. Each year we present a simple budget and the congregation supplies us with what we need. If I need a new car or a washing machine, I can call on them for it.

Mary uses handmade paints on We Are of the Gods.

“So I have more security than somebody else who is struggling alone. But I’m not free to just spend money – and I wouldn’t want to. That’s one thing about being a sister – we live simply as a matter of principle. We’re very dedicated to social justice so we take a big part in justice meetings and petitioning for specific causes.” Mary’s work is sold through Timaru’s York Street Gallery and a small roadside gallery in Athol in Southland. But most of her paintings are available through Crafted, the artisan’s collective in Oamaru’s Victorian precinct.

- The table set for a simple, delicious lunch.

- Mary’s version of a classic icon, Christ Pantocrator, hangs above her paint brushes.

- Her portraits of her family are watercolour works on linen.

- Pouhou, the waxeye at the bird table..

- Her home in the grounds of Teschemakers is unpretentious and light-filled.

Mary says Crafted provides another community for her. “Fifteen artists and artisans from throughout North Otago; each member contributes half a day each week to running the gallery. We pay a commission and an artist’s fee to cover overheads. We hold a monthly meeting and socialize from time to time.” It’s a Sunday in late winter and Mary has issued an invitation to her house for lunch. But first, it’s off to the Waitaki farmers market where she buys ciabatta from Ed the Dutch baker and a selection of Whitestone Cheeses. It has been raining but the sun comes out from behind the clouds. It sparkles in the puddles and Mary, as Mary is want to do, does a little light-hearted dance.

SISTERS-IN-ARMS

A photographic print of Mother Gabriel Gill, the foundress of the New Zealand Dominican Sisters in 1871, hangs in Mary’s house.

Dominicans worldwide are very much into women’s issues, Mary says. “Some years ago when it was a big topic, one of our sisters was very active in working with Filipino brides, another was working in women’s refuges. We are active in raising awareness of, and petitioning against, modern slavery. We speak out about the conditions of migrant workers here in New Zealand. Internationally, the Dominican order of both sisters and friars has a permanent social justice desk at the UN.

The chapel, seen from the altar looking towards the rose window, once rang with the sound of schoolgirls singing hymns.

Mary has taken a principled stance to her environment. “I was born in 1938 and moved five times before age four; therefore there was a sense of not knowing where you belong in the land. I have lived here at Teschemakers longer than I have lived anywhere else. In religious life, we kept moving. So, since the early 1990s, I have been able to claim the Waitaki River and Aoraki (Mt Cook) as my river and my mountain, but before then I didn’t have either. I didn’t have that sense of belonging.

“And because I became attached to the Waitaki River, I helped organize a protest exhibition – Artists Against Aqua – at the Forrester Gallery in Oamaru in 2003, and put in a submission to the Environment Court opposing Project Aqua, the damming of the Waitaki. “There were several others with me including film-maker Bronwyn Judge and Anne Te Maiharoa-Dodds of Waitaha, and we made a submission together on the spirituality of the river –the right of the river to be a river feeding the people around it.”

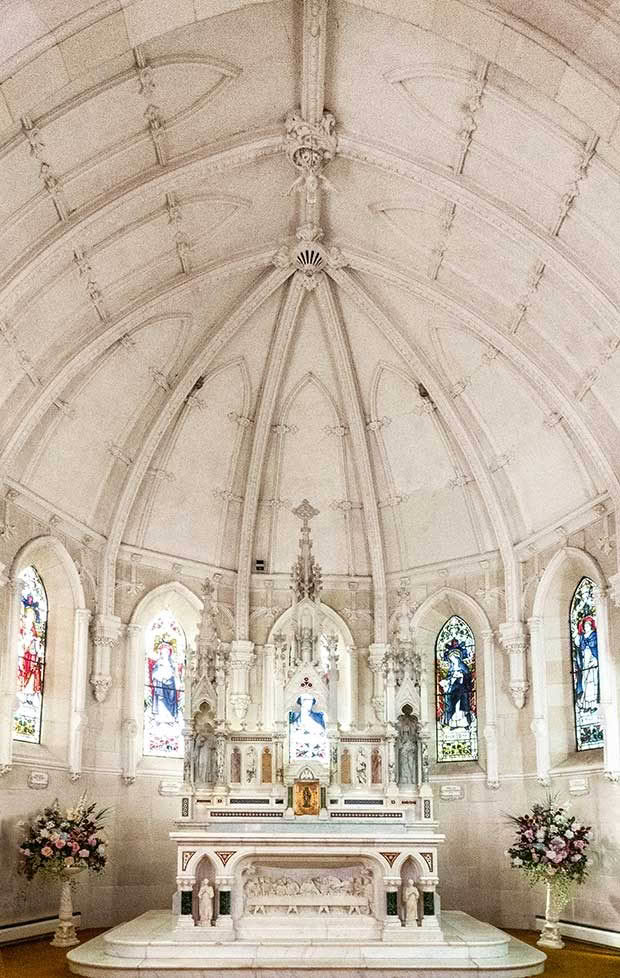

The sweep of the chapel’s sanctuary with the altar and stained-glass windows.

ON HIGH

The beautiful chapel in the grounds of the former St Patrick’s Dominican college, Teschemakers, about 10 kilometres south of Oamaru, was commissioned in 1912 and paid for by the generosity of a local benefactor from Oamaru, Frances Grant.

The Seventh Station of the Cross: Jesus Falls the Second Time.

It was designed by the prominent Dunedin architect of the day, F. W. Petre, completed in 1916 and named Our Lady of the Holy Rosary. New Zealand-born Petre came to prominence for his Gothic Revival-style architecture and is responsible for many of the South Island’s most beautiful Catholic churches of the era including the cathedrals in Christchurch, Dunedin and Wellington and basilicas in the smaller South Island centres of Timaru, Oamaru and Waimate.

After the Dominican order sold the former boarding school and convent property known as Teschemakers, a heated battle erupted over the glorious Gothic Revival-style Carrara marble altar with its alabaster depiction of The Last Supper. The Dominicans had given the altar to Holy Name parish in Dunedin.

But fierce opposition saw it remain after a ruling by the Environment Court. The altar had originally arrived for installation in 1918 from Italy in 19 numbered cases to be assembled like a jigsaw. The five magnificent stained-glass windows depicting various saints came from Birmingham.

Four nuns painted the 14 Stations of the Cross and beneath these are the names of the families and friends who made contributions to the costs of the building.

- The regular drawing group at Mary’s studio. (From left) model Helen Tse (in red), Burns Pollack, Mary and Ferne Smyth.

- Artists need a sense of community, says Mary.

- She has worked closely with North Otago artist Burns Pollack for many years while others, like Ferne, come and go within the group.

The Teschemakers complex has had several owners since the Dominicans sold it in 2000. Today it is owned by Chinese interests; the chapel, which is open to the public daily, is a wedding venue and the convent buildings have been converted to upmarket accommodation.

CALLED TO SERVE

It was another world when, in 1958, Mary entered the Order of the New Zealand Dominican Sisters. She joined a thriving congregation of 140 Dominican sisters but today there are just 40, mostly in their 80s. Very few religious orders take new postulants.

The Search, oil on canvas.

Sisters are women who take vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, who live communally and undertake apostolic work such as preaching the gospels mainly by teaching and nursing. Nuns live in strict enclosure, devoting their time to prayer and contemplation.

Mary was given the religious name of Sister Chanel named for St Peter Chanel. (Not the fancy French couturier but a French Marist priest who was killed in Futuna in 1841 attempting to Christianize the country.) She wore a habit, which became ever simpler after the Second Vatican Council (1962—65) cataclysmically freed many of the clergy and religious orders of Catholicism from the strictures of spiritual life. The Dominicans abandoned habits in the late 1970s and at the same time, Mary reassumed her own name.

North Otago 69, acrylic on wallpaper.

“We’ve largely abandoned the ritualistic elements such as rising at 5.30am for communal prayers and praying at a specific time of the day and evening,” she says. “At our age, we do what we can. I get up at about 7am but the old prayers don’t do anything for me these days. Painting is prayer. Gardening is prayer. However, the study of the scriptures is important to me. I spend 30 minutes in intentional silence daily.”

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.