Shipping container helps Kiwi kids learn science

This shipping container uses every square inch to nurture the future of country kids, and the adults too.

Words: Murray Grimswood

When someone creates a clever space and then that clever space is put to a clever use, it’s got to be worth writing about.

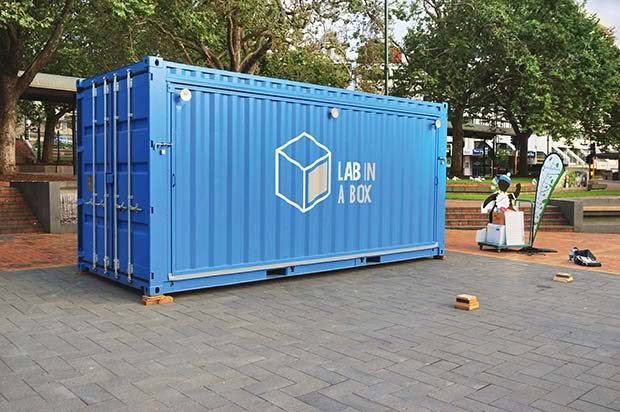

This particular space started life as an shipping container and goes by the name of Lab in a Box, or LIAB for short.

We first came across it via Jennie’s Enviroschools connection. She heard about it and thought it sounded interesting and very soon I was being asked to help get her worm-farm stuff to the LIAB for a couple of public education sessions being run at Dunedin’s Botanical Gardens. The photos from that day show that it clearly worked as intended, a classic example of clever space put to clever use.

WHAT IS A LAB IN A BOX?

This is how its creators explain it: “Lab in a Box is designed to be a resource to excite school students, communities and teachers about experimental science. We are aiming to work particularly with primary and intermediate age schools, but are also aiming to engage communities, and all students from ECE to tertiary. Participants can carry out science projects, eg a demonstration of rocket propulsion, an iwi investigating river health, a U3A meeting on astronomy, or a primary school looking at microscopic pond life. All these, and more, are the aim of Lab-in-a-Box.”

Associate Prof Dearden.

Peter Dearden is the originator of the idea. The Associate Professor at the Otago University Biochemistry Department also wears one or two other hats. Genetics is his thing, particularly genetics to do with bees. His initial reasoning was that geneticists are considered ‘evil’ and he thought a bit of good public relations wouldn’t go amiss. I have no problem with his assertion that genetics has changed our lives and our agriculture. His other comment – that genetics is fundamental to our health and our future – is another debate for another day. My reasoning is a can of petrol and a box of matches are both useful items but in the hands of someone with behavioural issues – the human race, in this instance – they can produce severely negative outcomes.

The other reason for creating a mobile laboratory is that it needs only one of everything, rather than each school or community buying equipment which would then spend 90% of its time gathering dust. You can think of the LIAB as you would a mobile dental clinic, always on the move and busy all the time. One bonus is that it can be left without a driver in attendance, or in fact without anyone at all

Peter Dearden talks enthusiastically about the looks on small faces in far-flung schools when they first see the likes of an ant under a microscope. He also points out that most science is hands-on and that the curriculum can be difficult for a non-specialist teacher.

Rural schools and communities are also where the rubber hits the road in terms of land use and water quality. These are the people who own – or will own – the resource so who better to teach the science to?

Tomahawk Lagoon, on the outskirts of Dunedin, is a good example. Its phosphate levels were sky-high, leading to the question of who/what is responsible? Water quality will increasingly become the ‘biggie’ if the push to intensify continues and the LIAB anticipates this by including pH, dissolved oxygen and salinity meters in its extensive list of equipment.

Designer Nick Sleeman was initially engaged via the Polytech to produce a CAD design to accompany funding applications. Starting with the idea of using a shipping container, his obvious problem was how to get a lot of bodies – 18 seated people was the design target – into a teaching space. It is an age-old problem presented by road-legal widths as 2.5m is too thin for a habitable room.

That’s why we see all kinds of pop-outs and hinge-outs on house trucks, mobile homes and caravans. The LIAB uses the time-honoured side pop-out method to essentially double the floor-space while making it squarer; a shipping container is 6m long and the pop-out makes the LIAB 4.8m wide. Nick says that not all the space is available, as given that the unit will spend time in places away from a power supply, there is a key-start generator on board, and other equipment too.

Science in action in the Lab in a Box

He says he wanted the workings to be invisible, or as near to it as practicable, so most of the opening mechanism is squeezed into the 200mm at the top of the container. But that led to a small problem.

“As soon as you cut into a container it is no longer straight and square and true.”

This – along with the need to keep glass stress-free – necessitated a levelling process which uninitiated folk could follow when opening-out the unit.

Pop-outs create three problems. The first two are weather-proofing them in the ‘in’ and the ‘out’ modes. Typically there is an inner flange, an outer flange, and some kind of rubber gasket. It may not seem problematic, but moving it at 100kph on a rainy day can sure show up the most obscure of capillaries.

The third issue is what happens if there is no local power and the generator fails? The ‘pop-out’ would be stuck in place so a manual pack-up system had to be sorted. There are good lessons here for anyone contemplating an expanding space, but eventually these curve-balls were ironed out (to well and truly mix metaphors). The day I watched it in action, the LIAB easily accommodated an audience of nearly 20 adults, one teacher, one facilitator and an unknown number of worms, all but the latter in sunlit comfort.

Funding is always the stumbling block for such a project. The LIAB was initially funded by the Ministry for Business and Enterprise (MBE) via something called ‘A Nation of Curious Minds’ (www.curiousminds.nz). In light of what I’ve written these last few years, it would be fair to say I think they’re on the right track.

Other support came from Rotary, Otago University, and there was a huge practical commitment from Icon Logistics who have been fantastic says Peter Dearden. A long-term funder/sponsor is still being sought. Peter thinks there is room in NewnZealand for two or three of the units and it would be a fantastic public-relations exercise for somebody.

As is always the case, it is much easier to obtain initial funding than maintenance funding, and it’s not hard to see why. A new idea/project/item can be shown-off, with political mileage to be gained, as everyone likes a new initiative. But maintaining an existing project? Where’s the kudos in that?

In New Zealand, we get these things started, then they get mothballed and it makes no sense. If the need has been recognised enough to seed them, so too should be the expectation of continued use, and therefore continued funding. The LIAB became ready-for-use last October. It did a ‘guinea pig’ stint at Kings High School, then hit the road around the bottom of the South Island.

In that time 5000 people went through it, a mixture of schools and pubic showings. It arrived back in February to get some inevitable bugs ironed out and it’s now raring to go again. The next stint is a full South Island circuit plus Stewart Island and the Chathams.

Even if the LIAB subsequently can’t find ongoing funding, it’s still a worthwhile attribute parked up somewhere, but it’s far more suited to being on the road. We’re going to need every little scientist we can get. It’s a cool concept, both in terms of the build and of the use to which it is put. Watch for it or get your local school to schedule a visit. It ticks a lot of boxes, and perhaps that comes with being one.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

MURRAY GRIMWOOD and partner Jennie Upton own a 24ha forest block north of Dunedin, but are currently sailing the seas on their yacht Sagamo. Murray likes to write, lobby, sail and create things.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.