The secret life of New Zealand’s bats

They may be on your property right now and they come in peace.

Words and photos: Diana Noonan

Additional photos: Graham Dainty, Colin O’Donnell,Stuart Parsons, James Mortimer

The night is cool and calm. A hushed air of anticipation ripples through the small but eager group gathered on a quiet, backcountry Otago road. Catlins’ resident chiropterologist (bat expert) Catriona Gower dons her high-viz vest. She looks up at the semiovercast sky and checks her watch. Sunset is officially 9.30pm but there is still plenty of light about.

She reaches back into her car for a bundle of black boxes and a clutch ofclipboards.

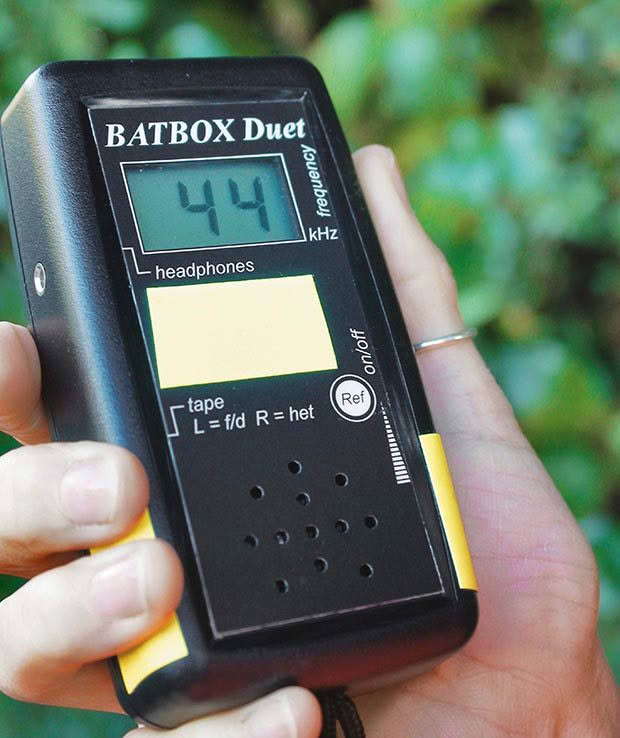

“Right,” she says, in her regional UK accent. “Who’s not used a bat detector before?”

I shuffle forward. Technology is not my forte, but I’m soon put at ease. Catriona has organised many similar events since her arrival here from the UK on Valentine’s day 2013 (she insists it was love at first sight) and is adept at educating the general public about bats.

She holds up the bat detectors and shows us how to tune them to the 40 kHz frequency required to hear the ‘bat chat’ we hope to encounter. She clicks her fingers together to imitate the kind of noise we might expect our detectors to emit and they give out a replying rasp of sound. Single ‘clicks’ will indicate bats flying in the near vicinity. Clicks in rapid succession will indicate bats feeding close by. To my relief, operating a detector couldn’t be easier, although for the experienced can glean a lot more information from the sounds. Catriona, for instance, can use bat chat to identify individual species and estimate the numbers of bats in a given locality.

Bat detectors mastered, Catriona then draws our attention to the clipboards and shows us how to record any chat that might come our way and the environment and conditions in which we would encounter it.

Our briefing over, we climb into cars and drive to the start of our destination, a 3km long strip of gravel road adjacent to the Tahakopa River and stands of native beech forest. Although there is no guarantee we’ll find bats (pekapeka) in this vicinity, Catriona grows increasingly hopeful as the headlights of our vehicle picks up dozens of dazzled moths and other flying insects. These are potential prey for the longtailed bat. It’s the species which inhabits this region of the country and which, unlike its cousin, the lesser short-tailed bat, prefers to catch its dinner on-the- wing. The proximity of the river also bodes well for a long-tailed bat encounter as wetland insects such as mosquitoes and mayflies are more likely to be fliers than those insects living within native forest itself.

New Zealand has two known living species of bat and they are our country’s only native land mammals. Both are regarded as endangered. Potentially, there may be one other species (the greater short-tailed bat) but insufficient data exists to support this.

My bat walk on this evening was unlikely to uncover any lesser short-tailed bats, given that the last known Southland sighting was documented in 1899 and the bat in question was caught alive, but later killed (and is now on display in the Southland Museum).

It all sounds interesting enough but when Catriona announces that some of the spots where bats have been found locally are in landowners’ own backyards, I am all ears. It’s not that I haven’t seen bats before; in fact I’ve spotted them in several parts of the world from New Caledonia to Greece, but to think I might have native bats on my own 2ha block is seriously exciting.

Our aim is to walk along the road at a 3km/hr speed, listen with our bat detectors, and watch for sightings.

Our feet crunch on the gravel. As it turns out, moving so slowly is not as easy as you might expect. We pass a herd of suspicious cattle, disturb a family of paradise ducks settling in for the night beside a drainage ditch, and catch the call of a morepork from the forest. I’m just about to comment on the bird’s haunting notes when Catriona begins her quiet patter as we wait for the bats to make their presence known.

Morepork, she tells us, are just one of the pekapeka’s notorious predators. Although owls are unlikely to capture more than one bat at a time, a single rat, stoat, or feral cat can kill an entire roost (up to 100 bats) in one night. There is also the theory that possums may prey on bats too. This is why, for those with bats in their backyards, or if you want to entice them in, predator control is so important. This is especially so during winter when roosting bats are immobilised for long periods by torpor, a semi-hibernative state lasting for periods of 6-10 days, the bats only emerging for a few hours or days for shorts bursts of activity.

The presence of standing dead or old-age trees with cavities is also likely to encourage bats onto a property. These kinds of trees are a favoured habitat of bats which roost in their hollows and under their peeling bark. The bats also use these hiding places for rearing their young which are known as ‘pups’. Landowners without mature native trees, says Catriona, should think about planting forest giants for future generations of pekapeka. In the meantime, purposeor home-built bat roosts made from untreated timber can be installed. Where few big native trees exist, even large exotics such as Pinus radiata can be helpful in providing feeding habitats for bats.

I’m about to ask just how to get hold of one of these mysterious objects when a soft rasp emanates from my bat box. Catriona stops in her tracks. The rasps grow louder and closer together and we follow her gaze to the runway of grey light sandwiched between the tops of tall beech trees and the hills on the other side of the narrow valley. Now the bat box is alive with sound. As I peer up at clouds tinged with a hint of moonlight, I spot a small silhouette so traditionally ‘bat shaped’ that at first I can’t believe what I’m seeing. A second later, we all spot it.

The bat’s wings are outstretched as it flutters, moth-like, then swoops up and around in obvious pursuit of prey. For the next 20-30 seconds, I marvel at the sight of a native animal I’ve never seen before, and never thought of as still living in my part of the world. I feel as I did the first time I watched yellow-eyed penguins waddle from the sea in the bay a short distance from my village; it’s such a privilege to have seldom-seen native animals so close to home.

Our bat flutters out of sight and everyone at once is full of questions.

“One at a time!” laughs Catriona, as delighted with the sighting as we are. Over the next half hour there are frequent stops to record the bat chat (alas, without further sightings) coming and going as we progress along the route. We learn a great deal more about our winged marsupial friends:

– they have the ability to fly at 60km per hour;

– they can range over an area of 100 square kilometres of territory;

– long-tailed bats travel up to 20km from their roost each night in search of food;

– in just one night they can consume up to 600 insects (and we’re talking about an animal that weighs no more than a quarter of a slice of white bread);

– as the lesser short-tailed bats go about their business, they play an important part in pollinating a number of indigenous forest plants including kiekie (a woody native vine), pohutukawa and wood rose, dispersing seed in their droppings and carrying it from place to place when it sticks to their fur.

As Catriona answers our questions with obvious enthusiasm, it occurs to me that these small, furry creatures which most of us know nothing about, hold something more for her than an academic interest. When a gap in the conversation allows time for a story, she tells us about Rose.

When she lived in the UK, Catriona once arrived at a veterinary clinic in response to a call to collect an injured bat. When she lifted back the bloodied cloth it was wrapped in, she knew immediately that the tiny creature’s injury meant it would never fly again. She had to make an on-the-spot decision, to agree to euthanasia or commit to 30-40 years of caring for the animal (as some species of bats can live that long).

“Actually, there was no decision,” she says. “I took Rose home, and she lived with me for seven years, at which point I handed her over to another bat-devotee from the local bat group who will continue to care for her.”

Rose rapidly adapted to her new life and now acts as a bat ambassador in much the same way as Sirocco the kakapo does for his species here in NZ.

Hearing Catriona talking about her is enough to make anyone want to sign up for chiropterology studies.

“Rose happily fed from my hand,” she says. “She liked sitting on my head, would purr on my shoulder, and enjoyed sleeping in the pocket of my jumper. Bats like to be at the highest point of whatever they are on and as Rose couldn’t fly, her exercise was to climb the flight of stairs in my apartment. I’d put her at the bottom and stand at the top until she climbed up to me.”

Many bat species, including New Zealand’s lesser short-tails, are as comfortable moving on the ground as they are flying, so when Rose finished her climb Catriona would return her to the bottom of the stairs and the work-out would start out all over again.

Bats are highly intelligent, social animals. They like the company of other bats, roost communally, and learn from and communicate with each other. If Catriona’s experience is anything to go by, they also relate well to humans.

I’d have been perfectly happy to listen to Catriona, and also to the bat chat, for the remainder of the night. But by now, apart from a few twinkling stars, the sky is almost completely dark and it’s time for our party to retrace its steps. As we walk in silence back along the dusty road, I am already making plans to purchase more predator traps, plant more canopy trees, enhance the small stream that runs through one corner of my block, and learn how to build bat roosts. I might also contact Earthlore Insect Theme Park (www.earthlore.co.nz), our local insect park, to see what plants are best to grow if I want to attract moths and other insects.

But there is one more thing.

“Catriona?” I ask. “Can I take one of your bat detectors home to check out my own property for bats?”

“Go for it,” she replies, and go for it I will. I may not have bats in my belfry, but by hook or by crook, if pekapeka are not already living in my backyard, I’ll be doing my darndest to make sure they soon are.

7 WAYS TO GET BATS ON YOUR PROPERTY

If you’re excited about the possibility of bats in your backyard, or want to entice them into your neck of the woods, you can:

• conserve large old live (and dead) trees on your land;

• if you don’t already have them, start planting canopy trees now;

• if you don’t already have a predator control plan, put one in place;

• enhance waterways or bodies of water on your land to encourage insect life;

• if you don’t have any bodies of water, consider developing a pond;

• research the best insect-attracting plants to grow on your land and plant them.

• install bat roosts on your land.

How to build a bat box

• For NZ-made boxes which you can buy online, visit: www.creativewoodcraft.co.nz/conservation/bats

• For plans on how to make your own, visit: www.bats.org.uk/pages/bat_boxes.html (scroll down to the bottom for free plans)

Note: if making your own boxes, it is essential to use rough-sawn, untreated wood or bats will be poisoned when they groom.

How to find bats

To check for bats in your area and to learn more about our only native land mammals:

• Contact your local council, DoC office or Forest and Bird group for information on how to borrow a bat detector, but if you have no luck, contact Catriona Gower of the Catlins Bat Project.

• Check out www.waikatoregion.govt.nz/projectecho/ and scroll down to the bottom of the page for a tip sheet on how to go bat detecting.

• Find out more about bats, and enquire about bat walks and education programmes, from organisations like: Project Echo www.waikatoregion.govt.nz/projectecho. Catlins Bat Project, Email catlinsbats@gmail.com. Auckland City Council www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz

• Excite your children about pekapeka – today’s kids are our next generation of conservationists.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.