Riverhaven Artland: Transforming an apple orchard into an art-filled arboretum in Clevedon

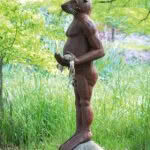

A trio of Katie’s cast bronze bittern or matuku (Botaurus poiciloptilus) maquettes (small-scale preliminary models) nestle into the reeds where the garden meets the Clevedon coastal estuary. Matuku, cousins of herons, cleverly mimic the raupō in which they “hide” by stretching their necks upwards while keeping their beady eyes on fish, frogs or eels below.

Five generations of the Blundell family have made their home at Riverhaven in Clevedon, south-east of Auckland, first as farmers, then orchardists, and now artists.

Words: Lynda Hallinan Photos: Sally Tagg

When you grow up in an apple orchard, perhaps it’s inevitable that you won’t fall far from the tree. For Clevedon artist Katie Blundell, returning to her roots has meant making a home — and a studio, teaching workshop and gallery — in the same 1970s barn where, as a child, she helped her grandparents bag fruit.

When Katie left home as a teenager, she didn’t go very far. She walked across the paddock from her family’s farmhouse and hot-footed it up the 11 macrocarpa steps, hand-sawn by her grandfather John and uncle Pete, to the loft above Riverhaven Orchard’s packhouse. Twenty-five years on, she’s come full circle with wife Sarah Nicholson, son Harry (13), daughter Lola (7) and Pablo the miniature schnauzer in tow.

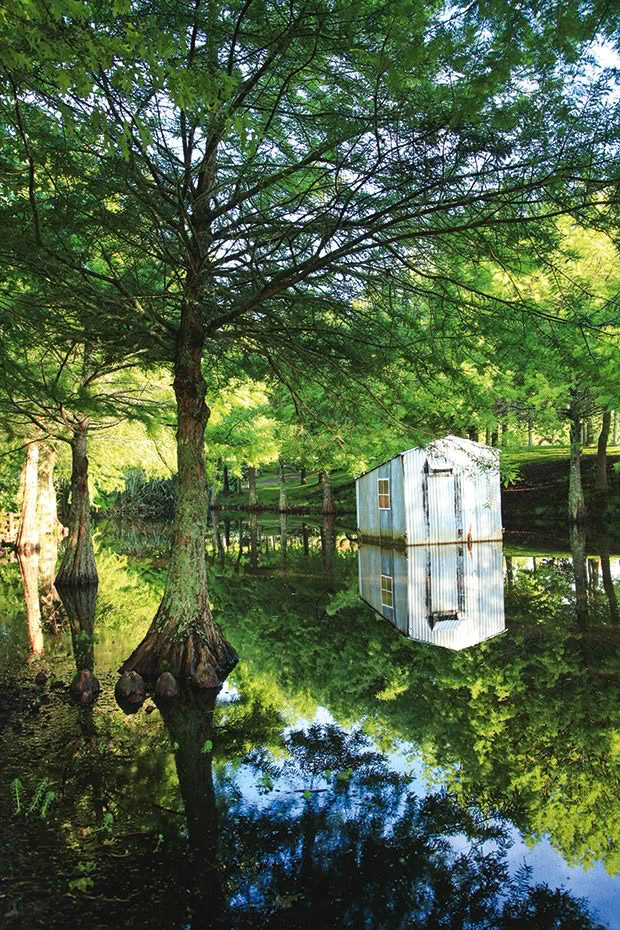

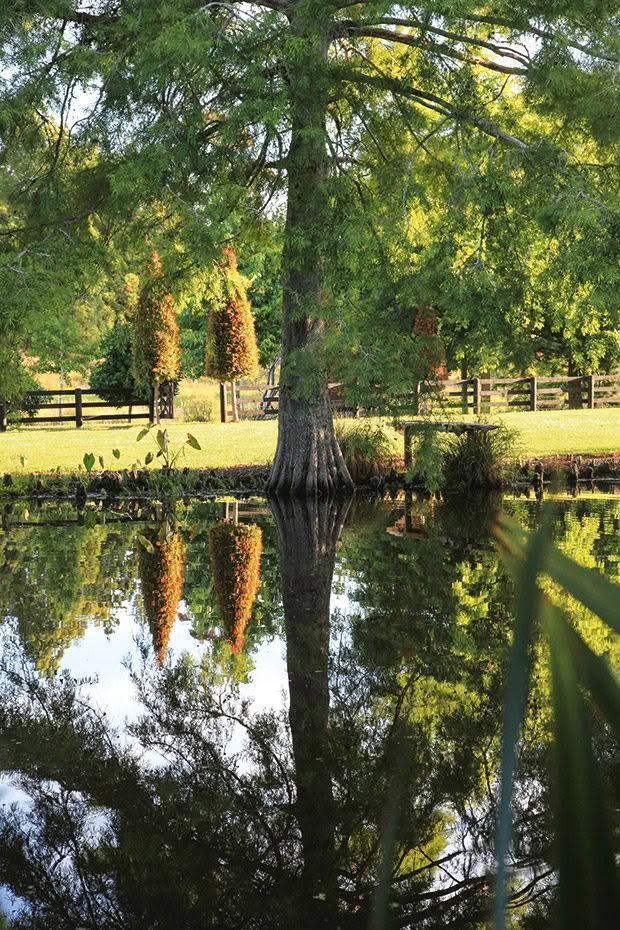

At Riverhaven Artland, the Blundell family’s Clevedon sculpture park, a floating corrugated iron shed reminiscent of a DOC tramping hut, casts a reflection between the swamp cypresses. Future Failings by artist Euan Lockie is a shed tethered to submerged moorings, which moves around at the will of the wind.

Having originally ditched the sticks for the city to study fine arts at the University of Auckland, Katie’s return to Riverhaven seven years ago was a homecoming and a healing. The eldest of three daughters, Katie had just turned 21 — her sister Anna was 20, and Sophie just 11 — when their mum Sue died from the rare lung disease, lymphangiomyomatosis. Sue was the first person in New Zealand to be diagnosed with LAM, a fatally degenerative condition the only cure for which is a double lung transplant.

Katie’s parents were teenage sweethearts who met at high school, and Guy, a practical chap more comfortable talking tools than feelings, was broken in bereavement. “I was completely lost,” he says. But rather than bury his grief, Guy chose to excavate it, carving out a creative future for the land his family has cared for for almost a century.

Katie Blundell (left) and wife Sarah Nicholson with their children Harry, 13, and Lola, 7, and miniature schnauzer Pablo.

Like Forrest Gump, who started running and didn’t stop for three years, Guy climbed into the cab of his seven-tonne digger and moved heaven — not to mention hundreds of cubic metres of earth — to create a 20-hectare arboretum park in his wife’s memory.

The English director Jamie Anderson once said, “Grief is just love with no place to go.” By digging, dumping, scraping and shifting soil on a grand scale, then planting thousands of trees, Guy was determined to create a place to honour his grief and his love.

Riverhaven was already possessed of natural beauty. This low-lying land — the highest point is just 7.5 metres above sea level — is bordered on one side by the main road north out of Clevedon, and on the other by the mangrove mudflats that fringe the tidal estuary where the Wairoa River greets the Hauraki Gulf.

Guy Blundell with cut branches of his favourite evergreen magnolia, Magnolia grandiflora ‘Blanchard’. In the background, the Fred Graham tōtara carving is Who Am I and was gifted by Jim Innes.

When Guy’s parents took over the farm from his grandparents, they milked cows and raised their six children in a relocated sapwood rimu army hut while they saved up to build their farmhouse in the 1950s. In the late 1960s, they diversified into horticulture, planting 16 hectares of fruit trees: ‘Golden Delicious’, ‘Granny Smith’, ‘Gala’ and ‘Vale Early’ apples on ‘Northern Spry’ rootstock; ‘Black Doris’, ‘Sultan’ and ‘Early Jewel’ plums; ‘Golden Queen’, ‘Fayette’ and ‘Paragon’ peaches.

When Guy and Sue took over, they sold crates of fruit and half-gallon jars of pasteurized apple juice at the front gate. But by the time Sue fell ill, the Apple and Pear Marketing Board’s export stranglehold had rendered the orchard unviable, and the industry’s deregulation in 2001 was the final blow.

- The rolling wagon-wheel gate was designed by her grandfather John, while the roadside bollards are recycled power poles.

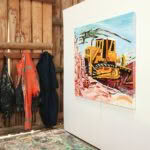

- From packhouse to arthouse: the heartwood macrocarpa barn where the Blundell family once picked and packed fruit is now home to Katie’s gallery and studio, where she works, lives and teaches art classes.

- Katie pegs On The Job Learning tea towel prints — a cheeky twist on how boys are taught construction skills while girls get to do the dishes — on a rope clothesline inside the gallery.

- She had her grandfather’s old laundry mangle wringer converted into a printing press by Waihī craftsman Johnny Mulvay of Classic Etching Presses.

- Working from home means it’s just an 11-step commute for Katie from the packhouse’s mezzanine loft lounge to the ground floor gallery and studio below.

- Katie’s painting overalls hang on the packhouse door. “I’ve worn my orange overalls every day for seven years,” she says, so the transition to a new blue pair is taking its time.

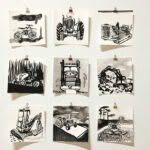

- This series of machinery drawings was made by Katie as part of inktober.com’s annual October challenge, calling on artists to create 31 ink drawings in 31 days.

Guy had always loved landscapes defined by trees — just not fruit trees. He’d had enough of them. Instead, he imagined undulating contours and serpentine lakes, with hidden corners and open clearings surrounded by groups and groves of elegantly limbed-up trees.

“We all dealt with our own grief in our own way,” Katie recalls. “I went off to study art at Elam [art school], and when I’d phone Dad to see what he was up to, he’d tell me he was digging holes and filling them up again. I had no real concept of what he was creating until we returned here to live, then I began to understand the magnitude of what he’d created, just by planting trees and waiting for them to grow.”

“I didn’t have a clue what I was doing at first,” Guy concedes with a chuckle. Indeed, it wasn’t until he’d worn out his original digger that he searched for landscape design inspiration and stumbled across the work of Lancelot “Capability” Brown.

Katie’s Farm Girl series was inspired by a tiki tour around the district’s farms to photograph “old fellas and their tractors”. The reduction woodcut print, Going Round in Circles, was ingeniously printed on the concrete floor of Katie’s gallery using an industrial roading construction roller. “It’s a Farmall Cub, a cute little tractor that looks like a miniature pony,” she says.

Capability Brown was an 18th-century English landscaper who literally made mountains out of molehills. He moved humps to make hollows, planted forests where there were previously fields and, if he thought a lake would look spiffing in a certain spot, he’d simply flood the nearest valley and build a bridge over it.

Just as Capability Brown’s naturalistic landscapes rebelled against the 18th-century fashion for formal gardens, Guy knew a traditional memorial garden wasn’t for him. “When I was a kid, Mum was a very keen gardener,” says Katie. “She made beautiful flower gardens, but Dad knew how much energy they took to maintain, and he didn’t want that style of garden.”

He does, however, rue not paying a wee bit more attention to one aspect of garden maintenance. “I wish I’d contoured the edges of the lawns better to make it easier to mow around the trees,” he says. Thus, it takes their groundsman Rob Dawson two and a half days each week to groom all the grass.

Sentinels of clipped lilly pilly (Syzygium australe) flank the gate leading from Guy’s private garden to the sculpture park. The adolescent swamp cypresses (Taxodium distichum) around the pond are beginning to develop their distinctive knobbly knees. Guy lowered the lake level until the trees were established to give them a leg up, then flooded their ankles.

Green-fingered friends and relatives — including Sandra Lusty from Rainbow Trees nursery, Sue’s sister Anne Bartley, who owned Thorndon Green Gardens in Wellington, Bev McConnell from Ayrlies Garden in Whitford, Morrinsville landscape designer Chrissy Lane — spurred him on with tree selections. Although Guy’s never stopped to count, over 20 years he planted thousands of deciduous trees, including claret ash, english beech, elms, liquidambars, nyssa, and knobbly kneed swamp cypresses (Taxodium distichum).

He’s also a fan of evergreen magnolias, particularly Magnolia grandiflora ‘Blanchard’, with its russet velvet foliage and creamy summer blooms the size of dinner plates.

- Katie and her family join Guy to dine alfresco in the grapevine-covered courtyard outside Guy’s home.

- The sculpture park is a natural playground for Harry and Lola. They ride their bikes along the meandering paths and perfect their kayaking skills on the pond.

Despite not working to a design plan, Guy had the good sense to group his trees by species — a dozen here, two dozen there — rather than assembling them in higgledy-piggledy congregations. In autumn, this means the fiery colours of the changing season ripple playfully across the landscape like the ribbons of rhythmic gymnasts.

Does he have any advice for other would-be arboretum establishers? “Don’t be a tightass,” Guy laughs. “You get what you pay for when planting trees, and as my ambitions grew bigger, so did the trees I was putting in.”

A few years ago, Guy had another ambitious idea. Around the Christmas table, he suggested to his three daughters that Riverhaven was the perfect setting for a contemporary sculpture park. “We all replied that it was a terrible idea,” says Katie. “But, luckily, Dad was very persistent because it has been wonderful as a growth project. We’ve all learned a lot along the way.”

Clipped lilly pilly lollipops. This folly of five trees stands guard at the roadside gate — one for Guy, Sue and their three daughters.

“It’s a beautiful place not just to live but to share,” says Guy. “Anna and Sophie are very supportive, and when we’ve opened for public events, all the grandkids also get involved and come to help out.” Riverhaven Artland has raised close to $100,000 for charities, including Franklin Hospice and the local primary school, in a little more than two years.

The first installation was a tongue-in-cheek collaboration of steel tubes titled Pipe Dreams. But the permanent collection has grown to include works by well-known New Zealand sculptors, including Fred Graham, Peter Lange, Jamie Pickernell and Jeff Thomson, plus emerging and local artists, including Katie.

Chris Moore’s sculpture Ornithophobia perches on a corten steel paddleboard.

“It’s quite a strange feeling to return to your childhood home as an adult,” Katie admits. “When we first moved back, we lived in the farmhouse where I grew up, and the walls were still the same bright shade of cheesecake yellow that Mum painted them. But so much has changed. It’s such a beautiful place, and that comes with feelings of responsibility as my relationship with Dad is now a creative partnership, whereas before, he was just Dad.”

Do they ever have creative differences? “Of course! We discuss things frequently and at length,” she jokes, “but Dad has always told us that if we’re passionate about something, we’ll find a way to make it successful, and we’ve always believed him because he lives by his own words.”

A GARDEN GALLERY

- Doctor Feelgood by James Wright.

- Between Two Trees by Cheryl Wright.

- Jamie Pickernell’s Beach Master.

- Anthills by Samantha Lissette.

The Blundells say it’s a privilege to showcase the work of local artists in the landscaped gallery that is Riverhaven Artland. The sculpture garden’s motto is “where nature greets art”, and each piece is carefully sited to reflect this sentiment symbiotically.

“It’s nice to build a network,” says Katie, who founded the Clevedon Art Trail along with Cheryl Wright and Maureen Conquer.

Riverhaven Artland is open to the public by appointment and as part of the Clevedon Art Trail (clevedonarttrail.co.nz) held each Auckland Anniversary Weekend. Katie also teaches art classes for adults and children and her gallery is open by appointment. katieblundellartist.com

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.