Recommended reading: Award-winning books worth their accolades

Our resident bibliophile dips into award-winning books from across the decades.

Words and Images: Meredith Hicks

Receiving an award for writing must be such validation for any author. To win for your debut novel, as three of the following did, must be the icing on the cake. Awarded from a range of notable categories, the following books span eras, countries and a range of characters, all with the underlying angst of being human and the fraught nature of relationships. See if there is one (or more) that you agree is worthy of the accolades received.

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Published 1960, Winner of the 1960 Pulitzer Prize

“Atticus was right. One time he said you never really know a man until you stand in his shoes and walk around in them.”

As I’ve aged, I have elected to read some of the classics that were missing from my younger years. I decided I had better try Ms Lee’s debut novel. The cover said ‘over 30 million copies sold’ so I felt this was a good sign.

I was engrossed by this book. Unusually, this book with quite adult themes is told from the viewpoint of a 6-year-old girl nicknamed Scout who has only a father Atticus Finch (the local lawyer) and an older brother Jem. It is a story about racism and justice, kindness and human connection set in the American south in the 1930s. Through Scout’s eyes, we get to experience a childhood marred by the inherent bigotry in the community where she lives, yet enriched by a father who models the right thing to do. There is the childlike fascination she, her brother and their friend Dill have with their reclusive neighbour Boo Radley and this is woven throughout the narrative.

This book is a cracking good story about a time and place in history far removed from many of our lives now, yet has so many comments to make about humanity and society that we can all relate to and reflect on. The relationships made in this book stirred my heart and Ms Lee manages to capture the innocent observations made by a child that ring so true, without judgment or hatred. After reading it I can see why so many millions of copies have been sold. It is an enduring classic.

Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman

Published 2017, Winner of the 2017 Costa Debut Novel Award, Overall Winner and Debut Novel Winner of the 2018 British Book Awards

“I do exist, don’t I? It often feels as if I’m not here, that I’m a figment of my own imagination.”

From the first page of this book Eleanor Oliphant was a character I knew I’d like. She was matter-of-fact, didn’t suffer fools and knew her routine each week. That she was a loner and a weekend alcoholic made me like her even more – if only because I felt sorry for her, yet impressed that she didn’t see the need to complain about her life. It was what it was and she just got on with it.

Things change when she spies the man of her dreams at a pub and befriends a colleague who accepts her as she is. As she focuses on improving herself, watching Eleanor develop relationships with other people and learning about herself feels uplifting and hopeful.

This cleverly written debut novel touches on many themes each with a place in the story. At its heart, it is made apparent that human connections are what we all need. Eleanor’s past has limited her ability to form these, but the kindness of others and circumstances lead her to discover that people can be good. For those of us who tend to ‘judge a book by its cover’ it’s a quiet reminder that behind every unusual person we come across, there is likely to be a backstory and if we just take the time to understand we might find we have more in common with these people than we realise.

The Promise by Damon Galgut

Published 2021, Winner of the 2021 Booker Prize

“No, no. It can’t be true…Nobody is dead. It’s a word, that’s all. She looks at the word, lying there on the desk like an insect on its back, with no explanation.”

I had not heard of this book until my daughter showed it to me when I needed a book for a challenge I was doing. It’s centred around an Afrikaans family in South Africa, starting in the 1980s at the height of apartheid and following their path of destruction over time. In the middle of this is 11-year-old Amor, who has recently lost her mother and seems to be cast adrift and forgotten by others in her family. It’s a social commentary on family life and the situation in South Africa as it follows the thread of a promise made to one of the family’s servants. It touches on the divisions between Christianity and Judaism and yet mostly it observes how dysfunction within a family can lead to its downfall.

I initially found this book challenging to get into. It is written primarily in stream of consciousness with no punctuation and it takes a bit to get into the flow of words but once achieved it carries the reader along from one person’s perspective to another. Their thoughts appear to flow into your consciousness and give the feeling of being inside the heads of the characters, listening in on their random thoughts while at the same time giving a feeling of normality to the train of thought running through your own head.

Mr Galgut makes clever use of metaphors throughout as he weaves this tale of an ordinary family living in a time and place of major social upheaval and I learned much about South Africa’s history. It’s a story about time passing and the changes that occur. After turning the last page I was left with a sense of having many things to contemplate for myself. Turns out this challenging book was well worthy of the prize it won.

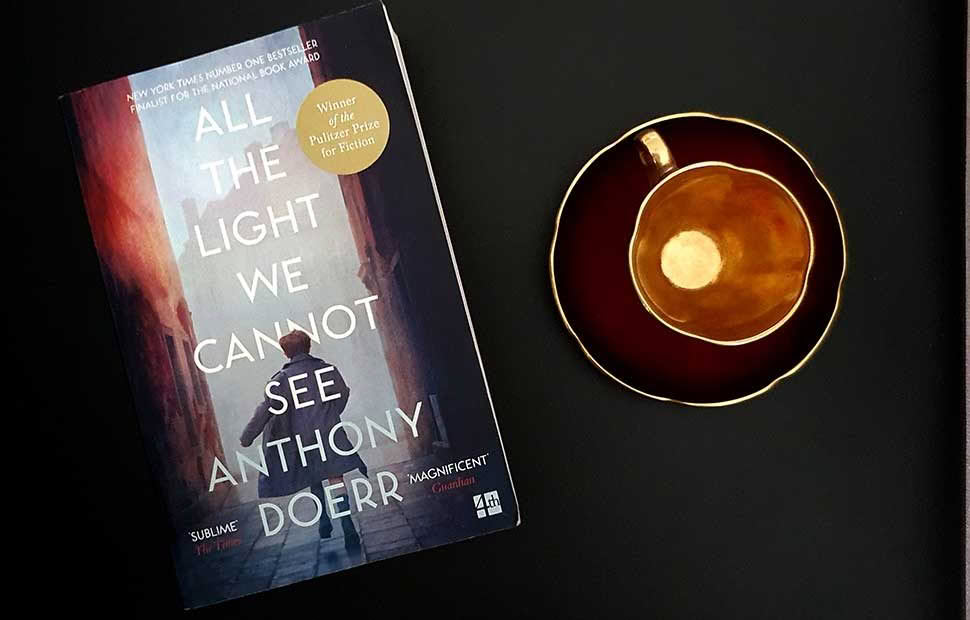

All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr

Published 2014, Winner of the 2015 Pulitzer Prize

“The parlour looks the same as it always has…Yet now there is music. As if, inside Werner’s head, an infinitesimal orchestra has stirred to life.”

There is something about this story that is compelling. It could be the WWII setting and the way it is written in short chapters going back and forth in time. Or it could be the heartfelt story of the experience of an atrocity by two young people distanced by miles and ethnicity.

Spanning 10 years, it opens with the 1944 Battle of Saint-Malo in France when Allied forces took this coastal town back from the Germans. It centres around Marie-Laure, a blind French girl living there with her father and great-uncle after escaping from Nazi-occupied Paris, and Werner, a German youth who fixes a broken radio as a child and whose talent sees him recruited by the Nazis. The reader is taken back in time to their childhoods and shown how they are shaped by people and circumstance and how, from quite disparate lives, the two end up being connected via the very technology that Hitler’s war machine is using. This is a story filled with despair, hope and a sense of the inherent goodness of humanity in the face of cruelty and hatred.

With Marie-Laure’s blindness we get a sense of her view of the world via Mr Doerr’s descriptive language of sound, touch and smell. For Werner, it is sound that is the life-changing sense for him with his fascination with radio waves. He learns about the world via broadcasts he tunes into as a child and this leads to his absorption into the Nazis, initially an escape for him from his life but ultimately seeing him doing things he doesn’t agree with.

At its essence, this book contemplates the wonders of the natural world alongside the wonders of the technological world, all against the backdrop of war. It stayed with me long after I finished and I will likely read it again one day to re-savour it. In the meantime, I look forward to watching the television series out now to see if it lives up to the original story.

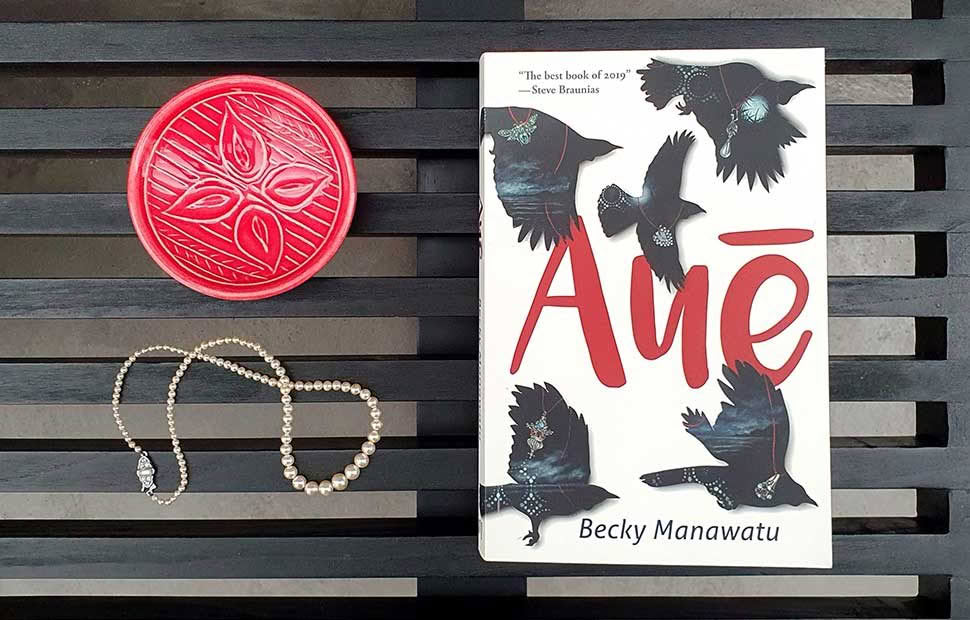

Auē by Becky Manawatu

Published 2019

Winner of the Best Fiction and Best First Book of Fiction at the 2020 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, Best Crime Novel and Best First Novel at the 2020 Ngaio Marsh Awards

“Taukiri and I drove here in Tom Aiken’s truck. We borrowed it to move all my stuff. Tom Aiken helped. Uncle Stu didn’t. This was my home now.”

And simply like that, we meet several characters in this wonderfully New Zealand story that is told with compassion and unexpectedly grabbed my heart. The cover attracted me at a book fair and from the moment I opened it I was drawn into the narrative – initially told from the point of view of an 8-year-old boy, then from his teenage brother. Interwoven between their stories is a young couple who meet and fall in love, causing two worlds to collide with disastrous consequences. Each page held words that immersed me into their lives in the South Island, lives filled with dysfunction and trauma. Despite this, the sense of hope and love experienced by these children is apparent and the mother in me felt for them.

Ārama is taken to live with his aunt and uncle near Kaikoura, left there by his teenage brother Taukiri who feels it is the right thing to do, even though it breaks his heart. Ārama’s young eyes observe the world around him, trying to make sense of what has gone before and what lies ahead, his vulnerabilities and unexpressed emotions held together by his obsession with sticking plasters that literally and metaphorically heal his hurt. Taukiri is a lost young man looking for himself in the wrong places, the legacy of his parents’ lives melting into his own and causing him to perpetuate their mistakes. Underlying all of this is a sense of family, heritage – both Māori and European – and the power of books, music and language that bind generations together.

This book is homegrown and heartfelt. The story behind its genesis is heartbreaking and the story within it touches on this heartbreak but is ultimately one of hope with characters who are now part of my psyche, never to be forgotten. This is definitely one worth reading.

Keep up with Meredith’s reviews on our website, alongside her Instagram page, When Books Become Air.