Ramshackle baches on the rocks: Meet the colourful community who holiday on Nelson’s historic Boulder Bank

The southernmost bach on Nelson’s Boulder Bank is owned by the Maxwell family.

Geologists have a saying — rocks remember. If Nelson’s Boulder Bank could talk, it would lay bare the goings-on that take place in the ramshackle baches on its stony shores.

Words: Emma Rawson Photos: Kate MacPherson

In Shetland island folklore, half-seal/half-female creatures known as selkies lure men into the sea at midsummer. On Nelson’s Boulder Bank, a strip of rocks on the other side of the world, Helen Inkster, the daughter of a Shetland Islander, tipped the tale topsy-turvy. Her highland dancing, accompanied by husband Bryce on the bagpipes, so entranced a fur seal one summer evening that it lumbered up out of the sea onto the stones to watch.

Te Taero a Kereopa/Te Tahuna a Tama-i-ea, the 13-kilometre natural spit of granodiorite boulders and pebbles in Tasman Bay, tends to attract the strange and unusual. Six weather-beaten baches, wedged in the rocks and perched on the boulders, harbour the small but colourful community who holiday here every year.

The area is only a five-minute dinghy ride from Port Nelson but is a private universe of tomfoolery and antics such as nocturnal nudie swims, golf on the tidal sandbar and waterskiing courtesy of an old wooden door. It’s all followed, in the evenings, by lots of whiskies.

The Inkster (blue) and Robson (red) baches above were both built in the 1950s by Phil McConchie. The pine tree planted by Helen’s mum Chrissie in 1970 is one of the few sources of shade on the bank.

In summer, the rocks are piping hot but when the sou’wester blows — strewth, she’s an ankle-rolling trip to traverse the few hundred metres to visit a mate in another bach. Walkers are forced into an exaggerated gait of cartoonish high-stepping. There’s no sand for sunbathing. There’s no running water. There’s no electricity. There’s no sewerage system. There are six pōhutukawa trees, stunted due to the harsh conditions (four are survivors of 13 trees planted by Helen’s mother Chrissie in 1970) and one pine, which is fully DOC-sanctioned because the environment is too rough for it to successfully reproduce.

One day a possum landed on the island, god knows why. Desperate to escape, it leapt into bach owner Alan Cederman’s trap.

The Boulder Bank families have saltwater in their veins. Helen’s late father, Gilbert Inkster, was Nelson’s harbour master for many years and bought their bach in 1965 for 350 pounds. At the time, the Boulder Bank was under the jurisdiction of the Harbour Board, and only employees could purchase them. The brilliant-blue bach was built in 1959, making it the baby of the group.

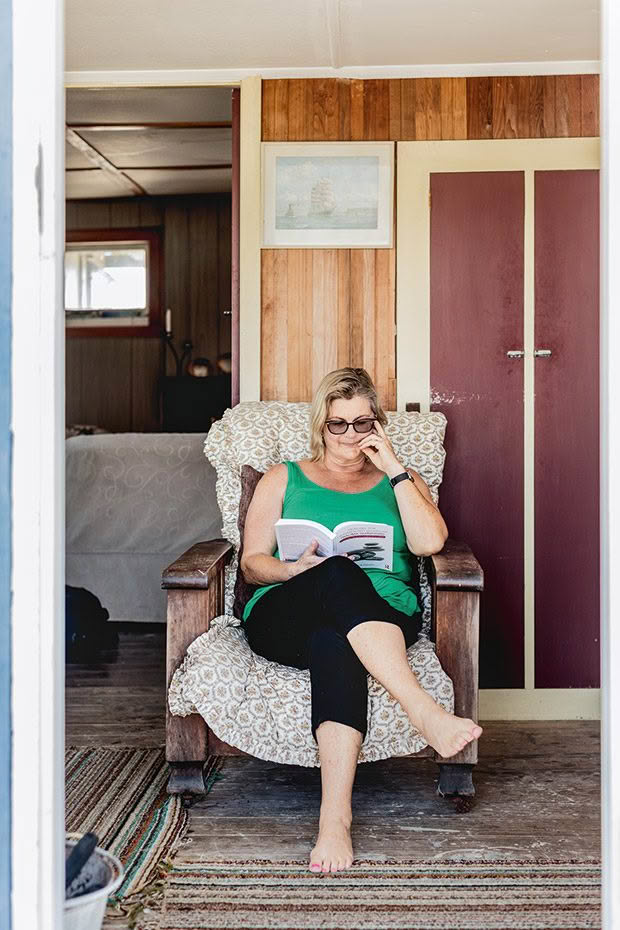

Helen, his daughter, likes to paint while at the bach and “reads and reads and reads” while on holiday, often in her favourite chair facing Nelson Haven.

Gilbert was able to commute to work by boat during the Christmas holidays, leaving the rest of the family enjoying an extended summer. But he never figured out a way to avoid getting his uniform wet and his wife Chrissie, a good strong lass, would carry him on her shoulders through the tide to his boat.

Helen and her brother Erik are now in charge of the boulder bolthole, and little has changed. There’s still no flushing loo, but a gas fridge has replaced a hole in the ground that used to store food. There’s a small generator occasionally used to power a few electrical items such as her ancient radiogram and, at night, the light comes from candles and torches. Erik complained about the “modernization” of the bach when Helen added a second-hand carpet one year.

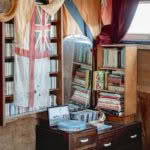

The interior of the front room was clad by Gilbert using salvaged cedar; candles are the primary source of light in the Inkster bach. “The electricity was put in the 1950s. I don’t like using it because I don’t trust the wiring,” says Helen.

“I like the simplicity of it,” says Helen, a psychologist. “Nelson is just over there, but it feels miles away. I sit and watch the birds and listen to the sounds of the sea. I’m so busy I don’t do a lot of sitting and reflecting in my everyday life.”

Out here, she feels she has more time for contemplation and perhaps even enjoying a candlelight whisky with her Boulder Bank “sister” Sue Robson. Sue, from the red bach next door, and Helen have known each other for more than 50 years. At one point, the baches, 50 metres from each other, shared a rudimentary electricity system. Their fathers also had a swap-pile of scrap metal and odds and ends that were used to repair the baches after numerous storms.

“We’ve known each other our whole lives. We’re all very different people, but we’re a close-knit community. I can tell Sue to piss off if I’m tired and I’m not up to conversation — it’s an easy relationship,” says Helen.

- The painting is of a sailing ship similar to the Pamir, a four-masted barque seized by the government in World War II as a prize of war. In 1945, the late Gilbert Inkster was a crewman on the Pamir on a cargo voyage to Vancouver.

- A a painting of Bill Clark aka Boulder Bank Bill, the sole permanent resident of the Boulder Bank for many years. His bach was nicknamed the “The Better Ole”, a play on the famous World War I cartoon, “If You Know of a Better’ Ole go to it”, which depicted two men in the trenches.

- She collects heart-shaped rocks and shells.

The Robson family bought their bach in 1969 and Sue spent her first summer on the bank aged 17. The bach, constructed by the same builder as the Inksters’, was purchased by her father Noel, an engineer on the tug Wakatu. The little red shack Sue now shares with her brother David is one of her favourite places. “What’s so good about this place is that I turn off my bloody phone, read a good book and have face-to-face conversations,” she says. “Or I just watch the world go by.”

Ten years ago, when Sue, a former nurse, was suffering from chronic fatigue, the Boulder Bank was her healing place. She loves it in a storm when every piece of corrugated iron rattles and the waves thwack against the steep rocks on the seaward side. During Cyclone Gita in 2018, six-metre waves sent spray crashing towards the bach and flipped and smashed her dinghy. In another storm, a piece of corrugated iron from the roof flew through the air threatening to slice her in half. She threw herself flat on the rocky ground out of harm’s way.

“You’re really up against the elements here, but it makes you appreciate the forces of nature,” she says.

Sue and her baby brother David share the Robson bach. Their father Noel, who had many jobs for Port Nelson, including engineer on the Wakatu tug and operator of the harbour dredge, bought the bach in 1969.

DOC took over managing the Boulder Bank from the Harbour Board in 1992 and, like other holiday properties on Crown-owned conservation land (such as the Rangitoto baches in the Hauraki Gulf and the huts at Orongorongo Valley near Wellington), the future of the Boulder Bank baches once hung in the balance.

Some argued that removing the baches would restore the bank to its natural state, whereas others thought that the baches, some of which date back to the 1890s, were historically significant. Records are vague, but there were initially eight baches, possibly nine. One burnt down and another, belonging to Bill Clark aka Boulder Bank Bill, was demolished when he died. Bill was a curmudgeonly but locally beloved Scotsman who saw rain clouds in every sunshiney day and lived permanently on the bank for nearly 40 years. Six baches remain.

- As youngsters Sue, David and their siblings used to play games in the waves that crash into the Tasman Bay side of the boulder pile.

- The winner would be the person who could hold onto a boulder the longest before the tide pulled them out to sea..

When it looked like the other baches might suffer a similar fate to Bill’s abode, Sue rallied the owners and worked with the New Zealand Historic Places Trust to protect them. They are now listed as part of the Boulder Bank Historic Area along with the lighthouse and recognized as typical examples of Kiwiana baches.

“When they tore down Bill’s bach, it broke my heart,” says Sue. “They are all built with odds and ends and things that have washed ashore, but they’re an important part of Nelson’s history. We’re not allowed to do them up, but none of us would want to change their character anyway.”

The Harris bach is only 150 metres away from the Robson bach, but it’s a slow five-minute walk on the rocky terrain. Bunj and Kim Harris’ father Jack, a wharfinger for the Harbour Board, bought the abandoned grey bach for 20 pounds for their family of nine in the early 1950s. Five generations of the Harris family have been arriving here ever since.

The Harris brothers, Bunj (left) and Kim (right), have heated games of cards at the bach: “We play Scum, and there’s a lot of lying and skulduggery.

“There’s little to do, and as kids we used to play simple games, building forts in the rocks and playing in the surf. It’s the same for the Harris kids that come here now,” says Bunj.

Jack’s ashes are scattered on the Boulder Bank as are the ashes of two of Kim and Bunj’s brothers, and Kim’s grandson. There has also been a family wedding. “This place is significant to us and a big part of our lives,” says Kim.

“When I come here, I can picture my mum walking around and dad working on something. I can feel them when we’re here.”

- The Harris bach was built in the 1890s as a fisherman’s hut and was then expanded into a two-bedroom dwelling, which can sleep eight.

- Initially, most of the baches had private jetties, but they weren’t repaired when parts floated away during storms.

- It’s an arduous 150-metre walk between the Harris and Robson baches. The Robsons’ red bach is seen here in the distance from the window of the Harrises’ side porch.

- The rocks get very hot in summer, and tank water is carefully conserved.

- There is no fridge, and a chilly bin keeps food cool; there’s no shortage of driftwood to burn in winter.

The Harris bach is one of the oldest, its first iteration in 1898 was a small shack built from kerosene tins filled with rocks. It was used by the fishermen who came to tar their hemp nets. Tar remains on the stones outside the bach. In 1912, the fishing hut became a one-room bach and, over the years, it was expanded to become 50-square-metre two-bedroom building.

The bach has no concrete foundation and is built straight into the rocks but, as Bunj says, it’s “solid as”. As kids, Kim and Bunj remember the kerosene tin wall was on its last legs by the 1960s, and they recall salvaging discharged shipping dunnage to use for bach renovations or firewood. A visitors’ log has been kept since the 1950s and names in it include poet Sam Hunt and the Beach Boys, who spent an afternoon surfing off the bank and based themselves at the Harris bach. In the summertime, it’s not uncommon to have a dozen-plus family members staying.

Like their father, Bunj and Kim are skilled seamen. Bunj, who the other bach owners refer to as a pirate, has sailed around the world twice and Kim was the Nelson Yacht Club commodore and took Princess Anne on a tour of Nelson Harbour when she visited in the 1990s. Kim and Bunj’s sibling rivalries are played out over cards and, at low tide, golf is played on the south-facing Nelson Haven sandbank.

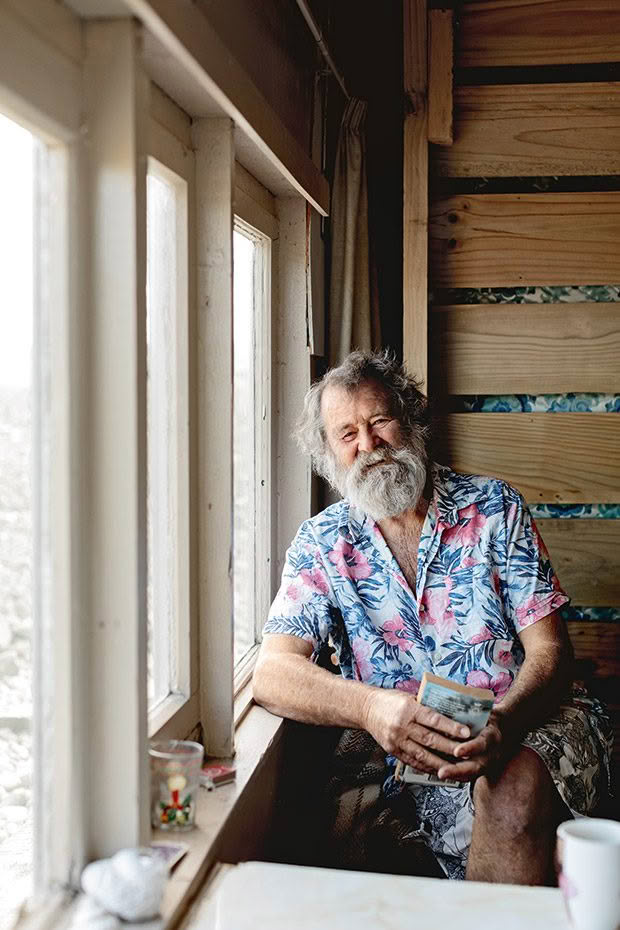

Bunj is an experienced sailor and has spent a lot of time living in the Pacific.

“We tried playing golf on the Boulder Bank once, and it was like playing pinball,” says Bunj.

The Harris bach is party-central now, but in the 1960s, the Robson bach was home to rowdy New Year’s Eve parties. A lot of whisky was drunk, a Boulder Bank mayor elected and, at midnight, a swim led by Bunj. One year, another bach owner, Wally Thompson, lost his false teeth in the rocks, and Gilbert Inkster once spent the night in a rock crevice, thereafter known as Gilbert’s Hole. The mayor’s responsibilities included making breakfast for the others for three mornings. The tradition has fallen into abeyance recently, but the mayoral chains await at the Robson bach.

Bunj says he might appoint himself mayor this year. “Life on the bank is a bit different, and we’re all a bit quirky. Who else would have a bach out here?”

Alan Cederman enjoys the peace of the Boulder Bank and visits nearly every weekend.

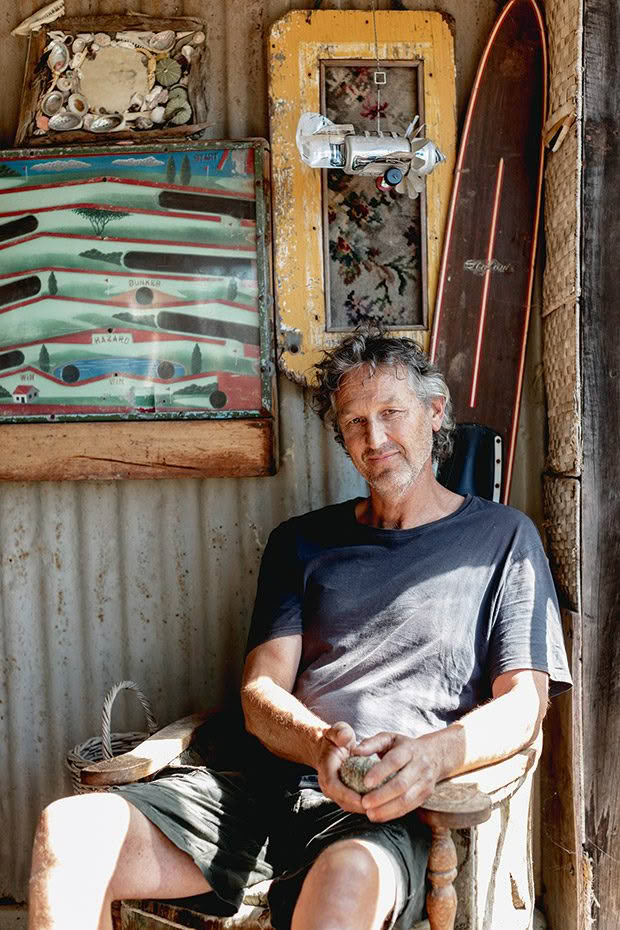

Alan Cederman is the new kid on the rocks because he bought his bach, with his partner Belinda, only 33 years ago. Fishermen built it in the 1890s using pressed Griffin’s biscuit tins to create walls. Alan works as a scaffolder in Nelson, hates modern buildings and avoids the internet, so he’s right at home in the old building. He enjoys the peace and visits nearly every weekend.

“I enjoy the serenity. As we push off in the boat, town life lifts away. I get in sync with the tides, and I slow down and relax,” he says. “People ask me if I get bored over here, but there’s always something to build or fix or something new on the beach.”

- The Cederman bach receives the brunt of the southwesterly winds but the structure, which has been standing since the 1890s, is robust.

- Powered by solar and a generator, the bach is filled with boardgames, books and cassette tapes so there’s plenty to do. Alan, however, prefers to create pieces of art from flotsam and jetsam found on the beach.

- The Cedermans’ double bed was owned by the Inkster family until a few years ago when some hooligans broke into Inksters’ bach and tried to make a raft from the mattress. When the bed “raft “washed ashore at the Cederman end of the bank, Alan took ownership of the bed because Helen couldn’t be bothered reclaiming it.

Each visit starts with a beach clean-up, collecting plastic and mussel floats that have washed ashore. The Cedermans’ yard is home to sculptures made from gathered driftwood and discarded bottles and hardy daffodils, which have survived 100-plus years on the bank.

As the water quality of Nelson Haven has improved, Alan has watched birdlife increase. The tarāpunga/red-billed gulls near the lighthouse dive-bomb passers-by and tōrea pango/oyster-catchers make it very clear who rules the bank while defending their fluffy grey chicks, perfectly and sometimes perilously camouflaged in the stones. The quirkiest Boulder Bank residents of all are the kōtuku ngutupapa/royal spoonbills, with their white ruffled crest and black paddle beak, that have returned to the rocks to nest in the past couple of years.

- Alan has created an archway and seating area from driftwood on the Tasman Bay side of the bank. He also collects mussel floats that wash ashore and sells them back to fishery companies in Nelson.

- All sorts of curiosities have found their way to the bank, including dolphin and shark skeletons.

While the heritage listing offers some certainty about the legal future, tide marks inching up the stones and getting closer to the houses is a new worry.

“Climate change will eventually take out these baches,” says Alan. “Living on these rocks, you become aware of small changes in nature. The tides are getting higher.”

ROLLING STONES

The Brady family own the northernmost bach, a gabled cottage built with parts of the old lighthouse-keeper’s house in the 19th century.

The Nelson Boulder Bank spans 13 kilometres and is the longest natural rock pile of its kind in the world. It was formed, more than 10,000 years ago when landslips in the Mackay Bluff (between Cable Bay and Glenduan) were swept southwards by strong sea currents. The bank varies in width from 55 to 240 metres depending on the tide, and the granodiorite rocks vary in size from large boulders several metres wide to cobbles and small pebbles.

The smaller rocks form layers, particularly from the wave action on the rougher seaward side. In 1906, a channel was dredged through the middle of the bank known as The Cut to improve access to Port Nelson. The Cut permanently separated Haulashore Island (once a tidal island connected to the bank). Boulder spits formed with large rocks are extremely rare, Nelson’s sister city in Japan, Miyazu, has a similar, but much shorter, rock formation.

ROCK OF AGES

The Nelson Boulder Bank Historical Area was listed in the Historic Places Trust in 2013. The bank shelters Nelson and is one of the reasons Māori settled in the region and, later, why it became an early colonial settlement. The lighthouse was built in 1862 and was New Zealand’s second permanent lighthouse. It was built from sections of cast-iron shipped from Bath.

The baches are listed as typical examples of Kiwiana, and the owners pay a lease fee once a year. The historical registry describes them as “Dwellings that show the essentials of what New Zealand baches once were before the word ‘bach’ came to mean ‘modern holiday home’.

Historically, the baches were under the jurisdiction of the Nelson Harbour Board, followed by the Nelson Council. In 1979, an annual licence cost a peppercorn one pound. Since 1992, the baches have been managed by DOC, and the licence has increased significantly to $847.50. But the owners are happy that their family properties are now protected by the Historic Places Trust.

They are small, weathered, quirky and unimproved. “From time to time, new materials can be spotted, indicating a level of maintenance.” A year after the historical listing, the bank, which has two names in Māori — Te Taero a Kereopa and Te Tahuna a Tama-i-ea — was also given wahi tapu status.

This recognizes the significance of the area to several iwi, who historically used the bank for seasonal food harvesting and as a source of rock for tools. Te Taero a Kereopa/Te Tahuna a Tama-i-ea features in a myth about Kupe the earliest tupuna (ancestor) in Māori culture. The story says Kupe’s warriors Pani and Kereopa fled his waka near Nelson wishing to remain with tangata whenua in Aotearoa.

The bank was formed when Kereopa performed a karakia, which prevented Kupe from capturing him.

VISITING THE BOULDER BANK

Walking the length of Boulder Bank from its land connection in Glenduan takes three to four hours (or up to eight hours return) and requires suitable footwear. Great care should be taken with nesting birds.

The Haulashore Ferry takes people to the Boulder Bank, and Abel Tasman Sailing Adventures offers a harbour cruise, which features a visit to the lighthouse.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.