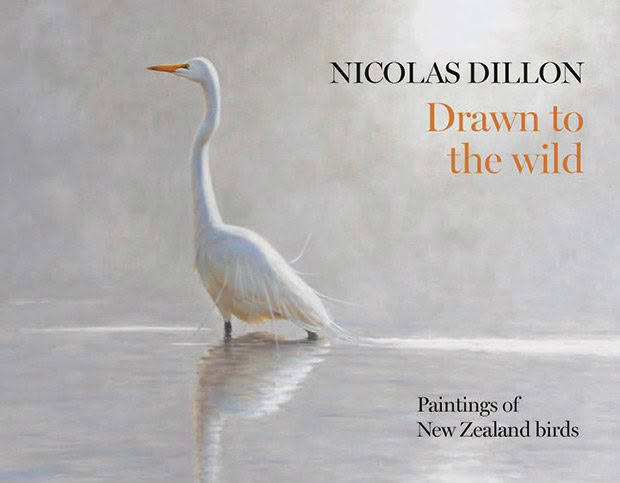

Q&A: Wildlife artist Nicolas Dillon on patience, painting in the wild and which NZ bird is the weirdest

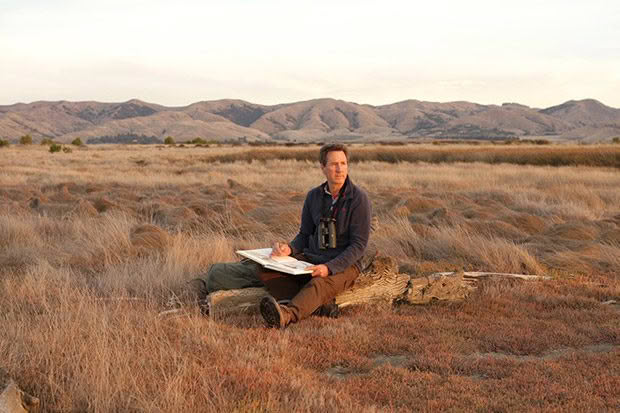

Marlborough-based artist Nicolas Dillon’s new coffee-table book of drawings and paintings of New Zealand birds represents his lifetime love affair with the natural world. He shares his thoughts on drawing in the wild, why he loves birds and what he’s learned from them.

Q: What is it that drew you to draw and paint birds?

Nicolas Dillon: My first memory in life is of a bird that flew into our window. It was a shining cuckoo (pīpīwharauroa) and I was mesmerised. As I held it in my hands, this iridescent, glittering jewel fired something deep inside. Perhaps that moment was the catalyst for my life-long desire to make images of birds. By the age of five or six I was drawing the natural world. Birds, in particular, have absorbed me ever since.

Shining cuckoo. Watercolour sketch, 2014.

Q: Why does the natural world call to you?

ND: I feel closest to my true self in the natural world. I experience a feeling of total happiness and freedom. Maybe it is just a form of escapism. Somewhere deep inside all humans is a latent connection to the natural world stemming from prehistoric times when we were a more integrated part of it. Michael McCarthy touches on this in his wonderful book The Moth Snowstorm. For me the natural world is endlessly fascinating.

Q: How do you think your life has been informed by the many long hours you have spent out in the wild observing the creatures of nature?

ND: I have always been happy to sit and look. The long, slow observation of things and birds in particular has instilled a certain patience. I think this has become without even trying a form of meditation. It’s a little trendy these days, to seek to attain this state called mindfulness. It is something we could all do with a little more of. If we took time to sit and look maybe we would be a little more in-tune with our environment.

Q: How long do you spend, typically, studying a bird, with your telescope and drawing gear, out in the wild?

ND: These moments can be as short as a couple of minutes or in some instances I can spend a whole day filling a sketchbook with pages of drawings and watercolour sketches. Even a fleeting encounter can leave an indelible memory. It is a bit like driving, when you see something out the car window as you speed by, that split-second moment can etch itself on the retina. Sometimes brief moments can be the strongest. If a bird is resting or quietly feeding, I often make quite detailed watercolour sketches in the space of 15 to 20 minutes. That is a relatively typical amount of time for one study.

I love the days where I lose all sense of time. If a bird is hanging out in one area, I can stay with it for many hours and become very familiar with its personality and the little details that define its character and individuality.

Q: What have you learned from 30 years of drawing birds?

ND: The more I’ve learned, the less I feel I know. More than anything I’ve come to trust my eyes and experience in the moment of observation. That it is only me who is seeing this and it it is important to capture that in my painting or sketch. It will be my vision, my interpretation and not coloured by any preconceived ideas.

Q: What is the most surprising thing you have ever seen?

ND: I was living in north Norfolk in England, when an elderly lady came knocking at my door one morning. She was in a dressing gown and slippers and lived in the house next door. In a high state of excitement she said I must at once come to her bedroom. I think I was more alarmed than she was. An eagle had flown through her window and was apparently perched next to her bed and I was the first person she thought of. I was now even more alarmed as eagles were not a part of the north Norfolk avifauna and, as far as I was aware, didn’t make a habit of flying through windows anywhere in the world. Sure enough, there was a gaping hole in the window and glass everywhere, but no eagle. It had gone. She looked under her bed and out shot a tiny partridge but no eagle.

Q: Do you have a favourite bird?

ND: I find it hard to single-out a particular bird species as a favourite. I used to say the karearea (New Zealand falcon). But tara iti, the New Zealand fairy tern, our rarest bird is definitely a favourite. Last year I had an incredible four days working very closely with them. They are so small and delicate but have an extraordinary tenacity. Every ounce of which they need if they are going to survive.

“Tara iti – Reflections.” Fairy tern. Oil on linen. 950 x 1200mm. Private collection, 2020.

Q: Your 21st birthday was special thanks to a peregrine falcon?

ND: I was sitting out in big rolling moorland, in Scotland in the mid August and the light was hazy, almost smoky in appearance. I had been sketching red grouse and northern wheatears when suddenly the birds fell silent and cowered amongst the heather. Out of nowhere a stunning male peregrine pitched onto a rock right next to me. It was utterly dazzling and in near perfect plumage. It seemed to evoke the very essence of wildness and I felt as though it had been sent to me that day. I was numbed by its presence.

Q: Is a royal spoonbill the weirdest looking of NZ’s birds?

ND: It is another of my favourites. Its huge spatulate bill, which is like a carved tribal artefact, looks oversize. Their red eyes are set-off by bright cadmium yellow eyebrows and right in the middle of the forehead is a patch of red skin which can be quite prominent in the breeding season. All this is topped-off in spring with beautiful white head plumes which hang and drift this way and that in the breeze. They look weird and beautiful all at the same time and appear to me to be descendants of a very ancient tribe.

“Spring Evening.” Royal spoonbills. Oil on linen. 800 x 1200mm. Private collection, 2018.

Q: What is your most memorable moment as an artist?

ND: The most memorable moment in recent years was early one morning on the Mangawhai Sandspit when I witnessed 18 juvenile bar-tailed godwits touching down after nine days flight direct from the shores of Alaska. These birds were only a few months old and unaccompanied by adults, they had navigated their way across the vast belly of the Pacific, airborne all the way. It seems beyond belief and I looked through my telescope into their dark confiding eyes and sensed something of that indomitable spirit.

Q: Most of your paintings seem to be of settled birds, feeding or wading, rather than on the wing — is there a reason for this?

ND: Flying birds are difficult. However, that is not answering the question correctly. Apart from the fact that resting birds make great models, there is also something about the meditative, reflective state. Maybe as much as it is about the birds, it might be about myself, and my own presence in nature in those moments. The seeking of tranquility and equilibrium perhaps.

Q: Do you paint in both oil and watercolour?

ND: Yes, I use both mediums. Watercolour is perfect for the quick sketch in the field, to spontaneously capture light and atmosphere. It is easy to cart around in my back pack. I use it for more finished paintings in the studio too and it is a wonderfully subtle medium very suited to rendering birds and plumage.

“Alone in the wilderness.” Takahe. Watercolour. 560 x 760mm. Collection of the artist, 2016.

I work in oils mostly for the larger paintings and when there are technical aspects that I can’t achieve in watercolour. Oils suit the longer game and also paintings where I may wish to change and play with the composition as the painting evolves. I love both mediums and it’s usually an equal split these days in terms of numbers of paintings in the two mediums.

Q: Have you observed differences in climate and environment in your 30 years of painting birds?

ND: The biggest thing I have noticed is the dwindling in numbers of migratory shorebirds such as – one of my favourites – the curlew sandpiper for example. We have to ask why this is and it is probably climatic and environmental. Environmental for these species in the sense that man has physically altered their habitat in certain parts of their migratory pathways. The reclamation and development of key wetlands and tidal margins where they feed.

Q: Is there a technical term for your style of painting?

ND: There are many ‘ isms ‘ in the world of art but realism and naturalism would apply to my work I suspect.

Q: Have you always been a self-supporting artist?

ND: I had my first exhibition when I was 18 and have painted fulltime ever since. Surviving as an artist financially is always a tough one. I was fortunate to have very supportive parents and that certainly helped me in the early part of my career. I feel lucky to have had that support which has allowed me to get to where I am today. It meant that I could do a lot more painting than I otherwise would if I’d been running a second job.

Winter hare. Watercolour. 560 x 760mm. Collection of the artist, 2012.

Q: You are largely self-taught other than teenage drawing lessons (shared with your grandmother) and close studying of many, many artists over the years.

ND: I didn’t go to art school and have had only a handful of brief lessons. I think in my case I was very singular in what I wanted to do. I knew right from the beginning that it was birds and the natural world which moved me most and inspired me to paint. I caught the bug early on and little has changed. It’s the constant looking and learning that I love. Trying to decipher techniques used by the great artists through studying their work in the flesh where possible. That has been one of the great joys. The quiet unearthing of techniques and wondering how I might be able to apply them to my own work.

Q: Do you have advice for any budding artists?

ND: To paint what they feel for most, what is really them. I see too many artists who just want to be an artist but don’t really know what they want to paint. They try everything that is trendy but can never settle for anything. You need to look inside, traverse the internal typography, plumb the depths of the soul and find out who you are.

Drawn to the Wild: Paintings of New Zealand Birds By Nicolas Dillon. Potton & Burton, RRP: $59.95, in stores now.