Polly Greeks’ Blog: A lesson from the children

All it takes is a different point of view to see wild pigs and whole grains from a new perspective

Sometimes when I’m blankly surveying the pantry for meal ideas, a flash of inspiration leads me to the buckwheat. It’s always the same. In my vision lie bowls of the toasted grain topped in a verdant homemade pesto.

In reality, there are never pine-nuts or parmesan, let alone enough fresh basil so I go on a scavenger hunt, popping in dandelions, kale, a fist of sunflower seeds here, a dollop of cider vinegar there, congratulating myself at the nutritious slurry whizzing up in the blender.Sometimes three-year-old Zen actually weeps when he sees what’s for dinner.

“I really hate you,” he sobs as he inspects the servings of beige and greying sludge on the table.

Last night Vita surveyed her dinner bowl in silence before asking for a piece of paper.

Earlier, we’d had a conversation about emotional maturity and how slamming doors/throwing objects and screaming were not constructive ways to express rage or frustration.

“Maybe I could draw how I’m feeling,” my six-year-old daughter had enthused.Seated at the dinner table, she scribbled furiously on a page.

“That’s not my hair,” she advised, stabbing a halo of red lightning jolts at a face. “That’s anger coming out hard.”

And so buckwheat with a serving of oxidized gloop falls to the back of the menu list, slowly shuffling its way forward again over the next few months until I’m gripped once more by a flash of inspiration for the reviled meal, accompanied by a firm conviction that this time, I’ll get it right.

I’m hoping the children will laugh fondly about such experiences as they reminisce in their dotage.

I’m almost at the stage where I can raise a chuckle at my mother’s culinary adventures.

Ahead of her time in the 80s, she belonged to an organic co-op and used to buy in sacks of wheat that Dad would grind into flour as a precursor to baking bread so grainily wholesome, I couldn’t even give away my lunchbox sandwiches.

Then came the announcement we were going to have a sugar-free, dairy-free, wheat-free year.

While other kids got to roll jaffas and snifters down movie-theatre aisles, I rustled a cellophane bag of dried pineapple pieces. At Easter, we hunted gloomily for carob eggs. Breakfasts were buckwheat. Spaghetti was made from corn.

I don’t remember the health benefits that allegedly rained upon us from our new diet. Instead, there’s the rather humiliating memory of pretending to be a poodle and begging with whines and panting for other kids’ chocolate biscuits at morning tea.

But history does indeed repeat itself. I now understand my mother’s motives weren’t about cruel deprivation. We are what we eat; organic beings not numbers. Much to Vita’s dismay I bake loaves of wholemeal sourdough instead of buying in bread; lentils, quinoa and chickpeas are menu staples. While I don’t inflict everything on the children, this year I’ve again gone sugar/dairy and wheat-free. As someone who used to wake up sneezing each day, the health benefits really are worth it.

Even though Vita would trade her wiggly front tooth for a loaf of fluffy whiteness, she’s become embarrassingly sanctimonious in supermarket queues at the check-out.

‘Look what they’re going to eat!’ she stage-whispers, followed by an open-mouthed dramatization of scandalized disbelief, as she critiques the trolleys around us.

She’s not so cocky back home in the bush.

In fact, ever since January when we were stampeded by a wild bush pig while walking through our forest, the children have been very reluctant to venture off the lawn. It’s as if the large black beast that shot towards us has left a porcine shadow hanging over the children’s psyches.

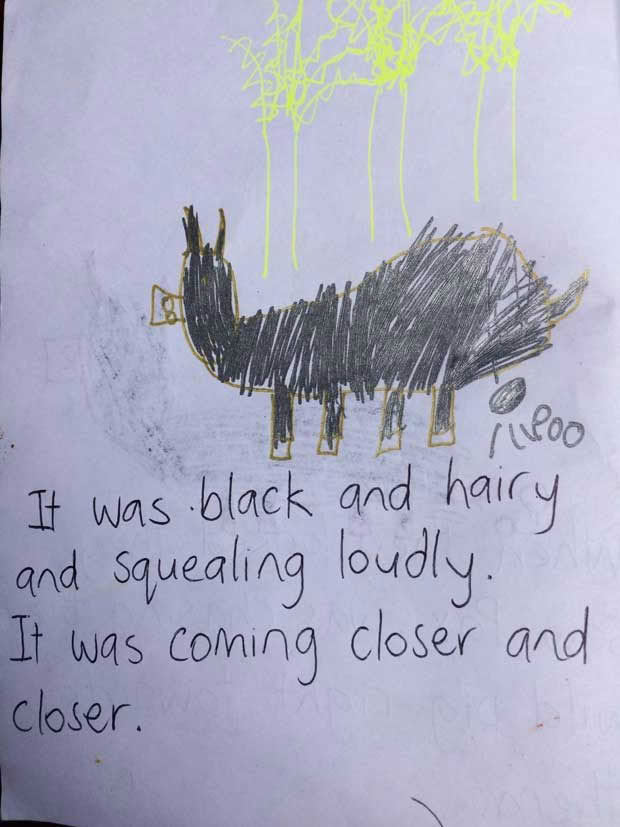

Proving that what makes an impression seeks expression, the kids have played ‘pig games’ for weeks on end, re-enacting events with much shrieking and heroic spearing. We’ve written stories about it and drawn thousands of pictures, while two months later, Zen is still building elaborate ‘weapons’ that will maim and shred a boar in several vigorous thrusts.

“We’re lucky, our bush is one of the safest in the world,” I’ve repeated like a mantra as I’ve ushered the kids through the forest on therapeutic walks since the event, but they’ve clung stubbornly both to my arms and their conviction that aggressive wild pigs lurk in every hollow.

Last week I tried a different tack. We’d gone on a hike up the stream, before clambering through dense bush to a ridge. Signs of pigs were everywhere and the children stuck to my sides like Velcro as we sat down for a snack.

“We’re so lucky we got to see a wild boar that day,” I bleated for the millionth time and then stopped.

In the silence that followed, I looked at my two wary children and thought about their perspectives.

Clearly, they didn’t consider themselves at all lucky or safe.

“Okay,” I said. “If a wild pig came at us right now, what would you do?”

An escape plan was hatched. There were trees we could climb. Zen, growing bold, found a stick to poke out its eyes.

It was like a key turning. By no longer insisting that everything was fine, I’d stopped invalidating their feelings. Acknowledging the realness of their fear had empowered the children.

Heading for home, we walked in single file, instead of lumbering awkwardly as a six-legged creature.

Zen found a kauri snail shell; Vita pocketed a strange lump of wood, but my treasure was inside me; a glinting reminder that children can have a whole other perception of the world that needs to be heard if we wish to understand their actions.