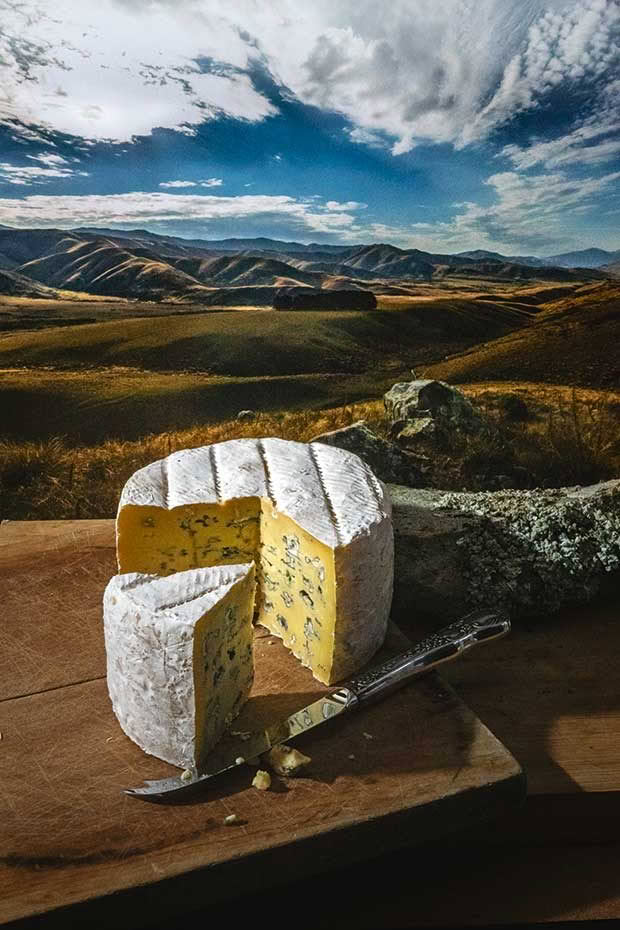

Oamaru’s Berry family are breaking the mould with a special blue cheese

Good things take time say the team behind the winner of this year’s NZ Life & Leisure spirit of New Zealand award.

Words: Lucy Corry Photos: Brian High

Simon Berry eats blue cheese on toast for breakfast. Not every day, of course, but he has to do his bit to support the family business. “I love all our cheeses, but the blue’s the best,” he says. “It depends on the season, because there’s so much scope. I mean, I do love the halloumi. But yeah, I’m definitely a blue cheese guy.”

It’s not as if he doesn’t have a wide variety to choose from. Whitestone Cheese, the company started by his father Bob and mother Sue back in 1987, now produces 25 different cheeses from its Oamaru factory. One of those cheeses — the Vintage Windsor Blue that Simon is so fond of having on his toast of a morning — is now exported to France. It also won a gold medal in the 2019 Outstanding NZ Food Producer Awards, along with Whitestone’s Ferry Road Halloumi (the highest scoring cheese in the awards) and its Vintage Five Forks.

Four other Whitestone cheeses — Lindis Pass Brie, Mt Domett Double Cream Brie, Probiotic Camembert and Windsor Blue received silver medals, and the Shenley Station Blue received a bronze. The Shenley Station Blue cheese and steak pies (available from Whitestone’s Oamaru cheese shop and at the Catalina Farmers’ Market in Auckland) also received a silver medal.

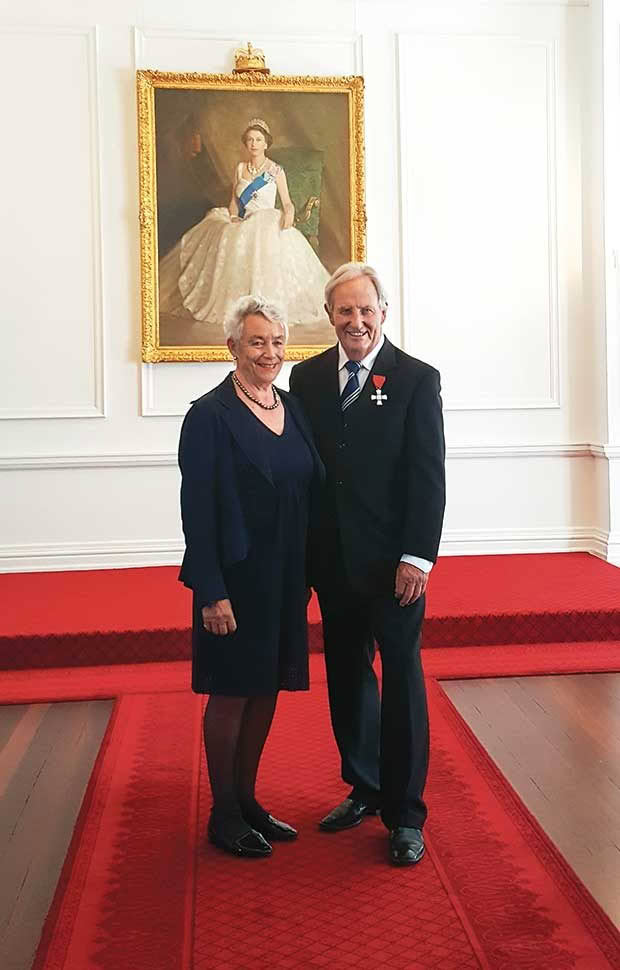

Simon Berry with wife Annabel: “When we win awards, it means something to everyone at Whitestone, whether they’re making the cheese or cleaning the floors.”

Whitestone’s long history of continuous innovation and improvement, often in the face of not-inconsiderable adversity, also saw them scoop up the Spirit of New Zealand Award, sponsored by NZ Life & Leisure. Editor Kate Coughlan called the company “a shining light” and praised the Berry family’s doggedness and determination.

“We’re an honest company, and we have a culture of understanding our wider community,” managing director Simon says. “We’ve built things slowly and steadily.”

Bob Berry wasn’t compelled to start the business by any romantic notions about cheesemaking; he just wanted his north Otago farm to stay afloat. In an environment churned up by Rogernomics and the end of subsidies, the catch-cry was “diversify or die”.

“Rural communities had been kneecapped and, on paper, 90 per cent of farmers were broke,” he says. “It was a huge adjustment.”

Bob pulled all the levers he could at the time, getting rid of most of his capital stock, switching much of his land over to cropping, and becoming a livestock trader. That kept the property viable, but he knew there was more to do. “I wanted to be a price-maker, not a price-taker,” he says “The wine industry was getting underway in Central Otago and what goes with wine? Cheese.”

Bob and Sue were inspired by hobby cheesemaker Colleen Dennison, who made cheese from the family’s house cow. They got some people together, built a small factory in a converted garage in Oamaru and hired a German chef to make cheese using milk from local farms.

The developing company’s first cheese, made to Colleen Dennison’s recipe, was rustically named Farmhouse. It developed a white/green natural rind and was not the most attractive thing for young Simon to have in his lunchbox.

“You had to have balls to try the thing because it was so ugly,” he laughs. “I was at primary school, and I remember everyone saying, ‘Eww, you have mouldy cheese.’”

Simon’s classmates weren’t the only ones to be wary. Bob took some to a deli in Christchurch, and the tasting went well until he told the deli manager the cheese was covered in natural mould. “She spat it out into her hand on the spot,” he sighs.

Nevertheless, the Berrys and their small team kept going. When Bob discovered he could import white mould from France, things started to take off. “All of a sudden we had a pretty-looking cheese and we were away,” Simon says.

Still, there were so many other things to get the hang of (like sales, distribution and pricing) that the actual cheesemaking sometimes looked like the easy bit. “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread,” Bob says. “It took us 10 years to make any money. But we would go to wine and food festivals, and there would be people standing three or four deep around our stall all day. We knew we were onto something.”

Whitestone Cheese founders Bob and Sue Berry. When Bob became a Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to the cheese industry in 2016, he insisted the honour also belonged to his wife, son Simon and the wider Whitestone team.

During that start-up period, Bob kept running the farm and outsourced the rest. He also realized the importance of embracing technology to help Whitestone stay connected to the big smoke. Bob was an early adopter of the “brick” cellphone, using it to stay in touch with cheese buyers in Auckland while he drafted sheep in the yards at home. “Dad always said it was ‘keep up or die’,” Simon says.

By the late 1990s, Whitestone Cheese was doing well enough to purchase the local Foodstuffs warehouse, move out of the garage and build a specialist cheese factory within the building. A significant export deal with a United States retailer meant they could expand further. Or so they thought. When the company’s category buyer changed, so did Whitestone’s fortunes.

“All of a sudden we were out,” Bob says. “Things were outside our control, and we realized that having all your eggs in one basket made you vulnerable.” They put their heads down and got through it, shifting production around to keep the factory running and the business intact. A young man called Chris Moran joined them straight out of school in 2000, Simon returned from a long OE to work at the company in 2003 and Bob sold the farm to concentrate on the exciting cheese business.

Fast-forward a few years and Simon is now the managing director. Bob remains a director (“Simon trots me out now and then, so I’m still very much involved”) and Chris Moran is head cheesemaker. Whitestone wins awards at every cheese contest going and has 50 staff working at the Oamaru factory, which also boasts a cheese shop/deli and hosts factory tours. They’ve recently opened premises at Hobsonville Point in Auckland, where an “affineur” (or ageing) facility allows them to experiment with maturing cheese and add value to their premium products.

A 2017 trip to France brought huge inspiration — and an unexpected export deal. Simon and Chris had taken a wheel of Whitestone’s much-awarded Vintage Windsor Blue with them on a reconnaissance trip into the global home of cheese, and they were gratified and delighted when their French counterparts were impressed.

“We had gone over to look at equipment, but we thought we’d take some cheese with us to show them that we knew what we were doing,” Simon explains. “The reception to it was incredible. So we thought, ‘Maybe we should try getting some cheese over here?’”

The first shipment — a not-inconsiderable 250-kilogramme pallet of cheese — was sent to France in late December 2018, with more planned this year.

“It is humbling to think we stack up with all those Old World cheeses that have been made for hundreds of years,” Simon says. “We’re operating at the same level, even though we initially made our facility with a bit of a number-eight-wire mentality. I think it’s just what Kiwis do. It’s like rugby or sailing — we’re always thinking about things a little bit differently and tilting to get that advantage.”

Looking further ahead, Whitestone wants to become better rather than bigger. “In five years, we want to have our Vintage Windsor Blue in all the world’s leading delis, and we want to produce world-class cheese for the New Zealand market,” Simon says.

“But we don’t want to be mass-supplying it. We want to provide a great cheese experience and lead the way in flavours. We think there’s growth in educating people about specialty cheeses.”

To that end, Whitestone operates an online cheese club, where members can sign up for a monthly or bimonthly delivery of cheeses, condiments, tasting notes and recipes. The company is also talking with Otago Polytechnic about qualifications in specialty cheeses. “We always have new ideas kicking around. Cheese is still an inspiring space to be in.”

See more on this year’s award winners here.

MILKING IT

The North Otago town of Oamaru is best-known in New Zealand for its built heritage. The town is blessed with an abundance of ornately decorated Victorian buildings constructed from locally quarried limestone.

That limestone, a sedimentary rock laid down millions of years ago when much of New Zealand was still underwater, also plays a part in creating Whitestone’s award-winning blocks of another kind.

Simon says the limestone soils in the area help promote flourishing sweet pastures, which in turn makes for great milk.

“Our location means we have a fantastic water supply, which runs directly from the glaciers of Mount Cook to our mineral-rich soil. We have a great raw product on our doorstep. That’s our point

of difference.”

BREAKING THE MOULD

French philosopher Diderot called roquefort — a tangy, creamy, crumbly unpasteurized sheep’s milk cheese marbled with blue mould — “the king of cheeses”.

Legend has it that the first roquefort was inadvertently invented about 1200AD by a shepherd who left his bread and cheese in a cave while he was chasing after a beautiful woman. When he returned (presumably without the woman or his sheep), he found the cheese was not only covered in mould but outrageously delicious. In the 15th century, the caves near the French village of Roquefort were given royal protection for their cheese-enhancing properties.

The mould there is named Penicillium roqueforti, and by the 1920s, roquefort produced in the area was given special status.

About 90 years later, Oamaru cheesemaker Chris Moran and Whitestone founder Bob Berry were idly chatting about roquefort and its flavours. For Chris, the penny suddenly dropped. “I thought, ‘Hang on a minute, there are plenty of limestone caves around here. Why don’t we go looking?’”

The pair then started a kind of boys’ own adventure, visiting caves all over the district and swabbing them in the hope of finding some magic mould. It eventually turned up in 2017 in a rather more prosaic place — a biodynamic beef farm in Fairlie. Farmer Rit Fisher was concerned when he spotted strange-looking mould on a bale of oat straw, so he sent it off to Plant Diagnostics in Christchurch to make sure it was safe for his stock to eat. When the lab discovered it to be a blue-mould strain similar to the famous French one, it called Whitestone.

Many tests later, the new mould was named 45° South Blue; the resulting cheese, Shenley Station Blue, was named after Fisher’s farm.

Last year, Shenley Station Blue was awarded 97/100 points at the world’s biggest cheese competition in Wisconsin. It was also highly commended in the 2018 Outstanding NZ Food Producer Awards.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.