NZ Lifestyle Block Smart Series Part Four: Architect Julie Villard’s eco home built is with cross-laminated timber — and a French touch

French architect Julie Villard has built a quiet, airy, compact smart home above a noisy port.

Words: Nadene Hall Images: Kirsten Sheppard

Who: French architect Julie Villard & partner Edward

Where: Lyttelton, 12km south-east of Christchurch

What: cross-laminated timber house, 9 Homestar

The elegant, clean roofline of architect Julie Villard’s smart house has a secret. It’s out in plain sight, but a lot of people don’t spot it.

“If you open an architectural book you’ll never see gutters or downpipes,” says Julie. “I wanted a detail for the roof and the wall where you don’t see them.”

Instead, the water falls over the edge of the roof and runs down the side of the steel cladding.

“The building code requires you to collect the water coming from the roof. You can collect it at the bottom of the roof or you can collect it at the bottom of the wall with a surface drain and that’s what we’ve got here. It’s my architectural feature, my French touch.”

It’s one clever little detail of this very smart house. French-born Julie is the eco design advisor for the Christchurch City Council. People get a free, two-hour consultation with Julie, who shows them how to make their new build, renovation or retrofit, warmer, dryer and more efficient. She is appalled at how New Zealand homes, even new ones, are cold and inefficient. That was a problem when she and partner Edward wanted to buy a house.

“We couldn’t find anything we liked to my European standards regarding energy efficiency and comfort. We went, ‘ok, we have to build’. Halfway through the process, I started my new role at the council… and I decided to use the house as a tool to show people you can achieve a good and efficient home.

Julie and Edward’s smart home is two-bedrooms and 117m². Look out for a full profile of the smart features of their home in an upcoming issue.

“By building a house following the (eco design) principles, I’m walking the walk, and at the same time showing people you don’t necessarily need a big house.

“It’s about needs versus wants. It’s about conscious choices. I prefer to build a two-bedroom house with a mezzanine – people can sleep there if we have guests – instead of having a third bedroom that we’re never going to use.”

The couple used the money they didn’t spend on size to pay for smarter options. For example, the underfloor central heating system heats the whole house and doesn’t cost a lot to run. The system was sized to the house with a room-by-room thermal analysis. Total cost: $13,000.

“We had quite high expectations of being warm. Ideally, reducing the size of the house allowed us to achieve the outcome we wanted.”

THE HOUSE

Size: 2-bedroom with mezzanine, 117m²

Design: Julie Villard, then working for Bob Burnett Architecture

Builder: Pomeroy Builders

Engineers: DO Davis Ogilvie

Walls: cross-laminated timber panels (CLT)| Hasslacher Norica Timber & Welstruct NZ

Weathertight membrane: Extrasana | Pro Clima

Insulation: wood fibre rigid external insulation | Gutex

Cladding/roof: shiplap cedar | BBS Timbers

Hiland Tray | Stratco

Windows: recessed, thermally-broken window frames with high-performance glazing | Hagley Windows

Underfloor heating: hydronic underfloor central heating system | H2Flow Plumbingand Heating

Ventilation: Lunos & Nexxt decentralised ventilation | The Heating Company

COSTS

Original budget: $500,000

Final cost: $542,000 (extra for retaining walls and foundations)

THE BRIEF

The CLT panels are not painted as Julie prefers the natural timber look. The cupboards in the kitchen form a privacy wall, so people walking past can’t see inside.

The site Edward and Julie bought is just 10.5m wide by 50m long, meaning the house had to be small and narrow.

“I grew up in France, with a family of four in 130m²,” says Julie. “I knew I didn’t need a lot of square metres for a comfortable-feeling home. It was a different story for my partner. Eddy comes from a bigger family, living in larger houses. At the beginning, he was triggered by the size of the house, only 53m² per level and 4.5m wide. He realises now, it’s actually not a small house… the walls on the first floor are 3m high and balance the long, narrow volume.”

Julie wanted to use cross laminated timber (CLT), a natural wood product, as the structure of the house. It meant she could design a warm, energy-efficient building because she could create a continuous thermal envelope, with no thermal bridges.

“In Europe that’s standard,” says Julie. “We insulate houses from the outside and CLT helped me to do that.”

Another important aspect was using products that didn’t require finishing.

“(CLT) is a natural, finished product, and we like the timber look. The concrete floor is also natural, no aggregate visible, so it looks like the concrete floor in a warehouse. “It’s just the materials, no cheating, no hiding, this is what they are naturally.”

The bottom level floor is concrete, insulated underneath and around the sides, and has underfloor heating. The first level is timber supporting a second, 70mm-thick concrete floor which also incorporates pipes for the heating system, and provides extra thermal mass. The special glass in the windows reduces the noise outside by up 36db, making it very quiet inside, despite being only 350m from a busy port.

WHAT IS CLT?

Cross laminated timber (CLT) panels are similar to plywood. The thick layers are solid-sawn lumber, glued together, pressed and cured. Each layer lies at right angles to the one under it, giving the finished panel structural rigidity in both directions. Panels can be custom-made to fit a project, and vary in size and thickness to give the required strength. CLT is a solid structural timber, but the panels can also serve as the finished interior surface (as in Julie’s home), with no need for linings, plastering or painting.

THE DESIGN

The hardest thing for an architect is to make a layout functional and simple. Julie’s inspiration was Lyttelton’s new Te Ana marina, and the local boat sheds. The home steps down a hill. The living area is at street level; bedrooms and a bathroom are down a flight of stairs, hidden behind the kitchen bench.

“Each level is only 53m², and because of the roof pitch and high walls, the house feels way bigger; and the simple layout helps quite a bit.” The main structure is cross laminated timber panels (walls, roof, floors), and steel portal frames.

THE BUILD

One of the things Julie likes about using cross laminated timber is that much of the house could be prefabricated.

“My background is in Europe and the way we build is prefab; having a product that was prefab was a big thing. The shape of the house was built in a week: on Monday, we had nothing; by Friday, we had a floor, a roof, walls – no windows, but the shape was done.”

Julie says building a house this way is different, but has big benefits.

“In general, the cost of materials is more expensive at the beginning, but the time to put all the panels on site is usually really short. In our case it was four days. For a house with a standard timber (stick) frame, the cost of materials is really cheap but you’re going to spend five weeks with labour to put it all together.

“At the end the cost should be even, if you leave it unfinished. If people start to plaster a simple CLT wall, you’re adding material, and the cost that goes with it, and this comparison won’t be legitimate anymore.”

Julie followed the higher building standards in the UK (for insulation) and France (for airtightness), rather than the minimums set out in the NZ Building Code. That’s why her house is the first in NZ to use wood fibre external insulation. The thick timber boards are screwed to the outside of the CLT and covered with a weathertight membrane.

“When I was working as an architect in Switzerland, this product used to be my standard. When we decided to build our house, I didn’t take a lot of risk because I knew the product.”

Unlike common insulation batts, wood fibre insulation is self-supporting and doesn’t need to sit inside a timber structure. Insulation that sits in walls and roofs can leave around a third of a house uninsulated due to gaps and light fittings. A gap the size of a finger can reduce the efficiency of 1m² of insulation by 30 percent (Source: Beacon Pathway).

THE WINDOWS

The double glazed windows have thermally broken aluminium frames that open upwards or are casement windows that open sideways for better air flow. The three-stacker sliding doors open both ways, a new, untried idea for the supplier. The windows are also sound-proof, important for this house which is just 350m from the busy Port Lyttelton.

“The port is really noisy, especially when they’ve got boats unloading scrap metal. The windows are designed to have a decrease of 36db from the inside to the outside so it’s very quiet inside.”

VENTILATION

Julie had to import her kitchen’s feature window, measuring 3.2m long, from a commercial window supplier in China.

When you have a highly-insulated, airtight house, it needs a good ventilation system to remove moist air, bring fresh air in, and maintain comfortable humidity levels. The windows play an important passive role. The upward-opening ones allow hot air out. The casement ones are perpendicular to the prevailing wind, allowing the couple to direct the outside breeze through the house.

“If it’s windy and we want to open a window, you’re not having a tornado going through the house.”

Two roof windows create a chimney effect, sucking hot air out on warm days. But this smart house also has a decentralised, balanced ventilation system. There’s no roof space for big ducting pipes used in common, positive pressure systems. Instead, small units in the bedrooms and a big one for the upstairs area, ventilate the air and recover heat at the same time.

“Each one has a little fan with a ceramic disc,” says Julie. “You’re warming the air in the room; the fan is extracting this air out for 90 seconds; the heat is stored in the ceramic disc. The fan stops and reverses and takes fresh air from the outside; the air goes through the ceramic disc, it pre-warms it, and it goes back into the house.”

Julie loves its simplicity and the figures.

“You’re recovering up to 86 percent of the heat. You get fresh air, but you’re not losing the heat, so that’s a major advantage. And it costs us $13 a year to run (3 cents per day), so it’s really cost effective.”

The bonus is Julie and Edward can enjoy the port view without smelling it.

“I can tell you this morning, we had two boats refuelling and it was smelling like petrol outside. This ventilation system has filters, so you don’t have the pollution coming in.”

The stairs are hidden behind the kitchen bench.

THE RESULT

When Julie is coaching people in her eco design advisor role, she uses her own house to show them what is achieveable.

“People might think you can’t do concrete on a first floor, and I’m like, that’s not true. They might think underfloor heating is really expensive, and I can say it’s not true, I’ve done it and this is how you could do it. “I really want to show people that you can do things differently. That’s why I’m happy to share what we’ve done.”

In 2018, the couple took part in the Superhome tour of Christchurch which showcased innovative houses built to very high standards, using smart design and products.

“For me, it was important to be open. We had 1500 people come through the house over three weekends.

“In my heart, I don’t want people to copy this house. I want them to grab something they like and use it in their own design.”

The languages of smart homes

THERMAL ENVELOPES

The walls, windows, doors, floors and ceilings of a structure all form the thermal envelope. A good ‘envelope’ wraps around a house to help prevent warmth getting out, and cold getting in.

THERMAL BREAKS

Some materials are poor insulators. For example, commonly-used aluminium window frames will stay cold and suck warmth out of a room, even if you have a heater blazing away inside. The cold aluminium meeting the warm air also creates condensation, leading to mould. A thermal break (or thermal barrier) is an insulation material placed inside or around a product or structure, to reduce or stop heat getting out, and cold getting in. Thermally-broken aluminium windows are made up of separate frames (one inside, one outside), with a layer of thermally-resistant plastic between them (the ‘break’), which insulates the frame. Timber, uPVC and fibreglass window frames are highly insulated.

THERMAL BRIDGES

Some products, like insulation, are thermally resistant. They slowly transfer heat which helps to keep a room warm for long periods. Standard 90mm timber framing doesn’t have good insulation properties. It’s a ‘thermal bridge’ because it transfers heat out of a structure at a fast rate. The more complex the design of a house, the more ‘bridges’ you’ll have. The more ‘bridges’, the higher the loss of heat, and the more it will cost to keep the house warm. Julie’s house doesn’t have the ‘bridges’ found in standard NZ builds, thanks to her use of CLT panels and wood fibre insulation.

SMART WINDOWS

Glazing is far more expensive to buy than building an insulated wall. Walls also have an R-value 800 percent better than a standard, double-glazed, aluminium window.

Smart homes typically have:

• less windows, especially on the southern side

• windows that are carefully oriented to allow gentle air flow, but not wind

• highly-insulated or thermally-broken window frames

• double or triple glazing

• high-quality glass, eg low-emissivity glass (low-E) which allows light and heat in, but helps to prevent heat from escaping

• laminated glass, to reduce outside noise

The windows in Julie’s home are thermally broken, double glazed, low-E, argon-filled, and reduce noise coming in by 36db.

THE R-VALUE OF WINDOW FRAMES

Frame & glass combination: R-value*

*window R-values based on a standardised size for testing

Standard aluminium frame with clear double glazing (minimum Building Code standard): 0.26

Thermally broken aluminium with clear double glazing: 0.31

Timber or uPVC with clear double glazing: 0.36

Thermally broken aluminium with low-E, argon-filled double glazing: 0.65

Timber or uPVC with low-E, argon-filled double glazing: 0.8

Standard insulated wall construction (minimum North Island Building Code standard, excluding Central Plateau): 1.9

Source: Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment

THE STAR HOMES OF NZ

Julie and Edward’s house has just been awarded a 9 Homestar rating (out of 10), the second in NZ to achieve this score.

Julie and Edward’s home has a 9 Homestar rating, only the second in NZ to achieve this world-class level of quality. Homestar is a comprehensive, independent, national rating tool that measures the health, warmth, and efficiency of NZ houses. It’s overseen by the New Zealand Green Building Council (NZGBC).

Most existing NZ homes would only achieve a 2-3 Homestar rating. Most new homes, which are built to the minimum standards of the Building Code, would achieve a 3-4. The best homes are rated on a 6-10 scale. A 6 Homestar (or higher) house will be warmer, drier, healthier, and have power bills approximately half those of the typical new build (3-4 Homestar). A 10 Homestar rating is a world-leading house in terms of warmth, efficiency, with minimal waste and environmental impact.

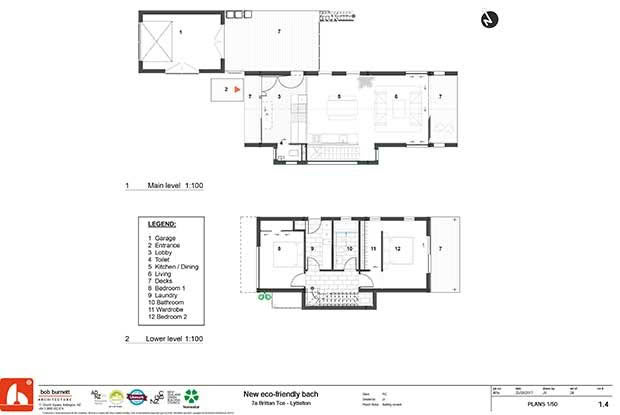

THE LAYOUT

1.Garage

2. Entrance

3. Lobby

4. Toilet

5. Kitchen/Dining

6. Living

7. Decks

8. Bedroom 1

9. Laundry

10. Bathroom

11. Wardrobe

12. Bedroom 2

Love this story? Subscribe now!

MORE FROM THE SMART BUILD SERIES

How New Zealanders can build smarter and more efficient homes

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.