What NZ gardeners and farmers can learn from Japanese Farmer and philosopher Masanobu Fukuoka

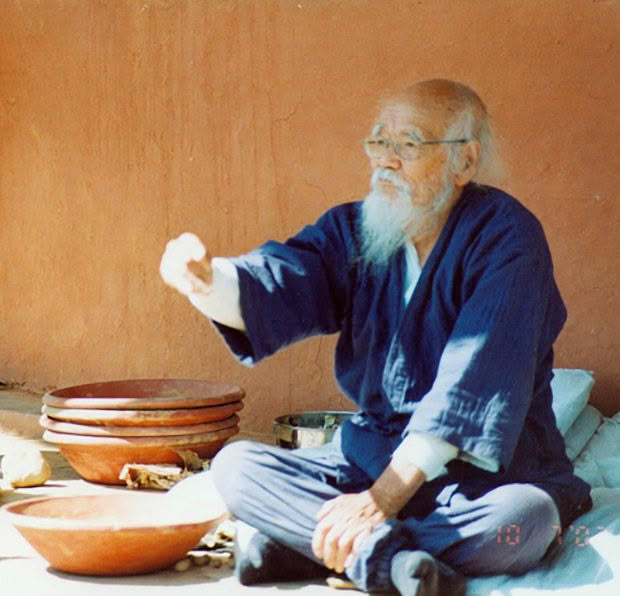

Japanese farmer and philosopher Masanobu Fukuoka. Photo: By naturalfarming.org , via Wikimedia Commons

A revolutionary way of farming that has no plowing, no fertiliser, no weeding and no pesticides isn’t as easy as it sounds.

Source: http://fukuokafarmingol.info/

The story of this revolution in farming begins in Japan in 1939 when a young man working as an agricultural customs inspector became sick with pneumonia. Very sick; in fact, he almost died.

For the student – Masanobu Fukuoka – his survival was a life-changing event. For years he had helped his family work their land but after his illness he had an epiphany; human knowledge was meaningless, and in this world there is nothing at all. Fukuoka-san came to believe that humankind’s attempts to control or even understand life was futile and self-destructive.

“Following my eventual recovery, I spent many sleepless nights wandering the streets. The morning after one such episode—when it seemed as though everything were about to explode in my brain—a flash of insight came to me. I suddenly felt that all human existence is meaningless and of no intrinsic value. Humanity knows nothing of real worth at all, I decided, and every action we take is just a futile, empty effort. I also saw that nature is ideally arranged and abundant just as it is . . . therefore, I was sure that we should work in cooperation with the natural processes, rather than try to “improve” on them by conquest.”

Mother Earth News interview, 1982

You may be wondering, what all this philosophy has to do with farming? As a farmer Fukuoka–san decided he would live his life and raise crops by this philosophy. That meant restoring the family farm land to a condition where nature’s harmony would prevail, providing a perfect place to grow crops without the need to plow, spray, fertilise or interfere with pest control.

Fukuoka began with what he had, an orchard of mandarin trees on his father’s farm. The first year he decided to let nature takes its course and didn’t spray, prune or fertilise. In fact he didn’t do anything at all and the orchard was destroyed by insects and disease.

He learned after that first year that there is difference between practicing natural agriculture and lazy agriculture.

“Those young trees had been domesticated, planted, pruned, and tended by human beings. The trees had been made slaves to humans, so they couldn’t survive when the artificial support provided by farmers was suddenly removed.”

Mother Earth News interview, 1982

Fukuoka’s methods aren’t “do nothing at all, ever” and he wrote they don’t involve throwing away all the scientific knowledge about horticulture. Instead, he says it is people working out what the unaltered state of their land is, so that they can work out the most natural way to get the best out of it. This may not be what we, as humans and as farmers want, ie if you want to grow bananas but you live on a snowy mountain.

“Many people think that, when we practice agriculture, nature is helping us in our efforts to grow food. That is an exclusively human-centered viewpoint . . . we should, instead, realize that we are receiving that which nature decides to give us.

“People should relate to nature as birds do. Birds don’t run around carefully preparing fields, planting seeds, and harvesting food. They don’t create anything . . . they just receive what is there for them with a humble and grateful heart.”

Mother Earth News interview, 1982

According to Japanese Farmer and philosopher Masanobu Fukuoka there’s no need to weed around your fruit trees. Photo: Dreamstime

THE 4 BASICS OF FUKUIKA FARMING PHILOSOPHY

1. No tilling

No turning or plowing of the earth, with soil left to “cultivate itself” using plant roots and the digging activity of earthworms, small animals and micro-organisms. For example, to plant a vegetable patch, Fukuoka cuts down the plants in the chosen area to form a natural mulch, (usually in and around the trees in his citrus orchard. Hethen mixes seeds of burdock, cabbage, tomatoes, carrots, mustard, beans, turnips and other herbs and vegetables, before hand-broadcasting it over the chosen area and covering them with the mulch. Anyway weeds that start to come back are cut down to allow the seedlings to grow. Grown this way says Fukuoka, vegetables are much stronger than people think. It does rely on you knowing what the life cycle of your particular weeds are, so you can plant out at the best time, and plant vegetables that will be able to compete with them.

2. No chemical fertiliser or prepared compost

The orderly cycle of plant and animal life will sustain itself eventually says Fukuoka, but don’t expect it to do this quickly. In first year of farming and growing in this manner, Fukuoka got a paddock that was 70% weeds and 30% productive. Over the next several years the paddock slowly got itself in balance as he continued his methods, and Fukuoka ended up with one of highest producing properties (per acre of crop) in Japan.

3. No weeding

Part of his success in increasing the fertility of his soil has been his use of weeds. This is an important part of the “do nothing” philosophy. Fukuoka believes weeds play a vital part in building soil fertility and helping soil biology, so he controlled their growth but didn’t eliminate the weeds in his fields. He also used white clover interplanted between crops, to keep other weeds under control.

4. No pesticides

By interplanting many different species, the pest damage was low in Fukuoka’s experience, because the biodiversity of the planting didn’t allow any one insect or pest to get out of control.

SUCCESS OR FAILURE?

When Fukuoka planted his first large-scale crops (alternating rice and barley), his low production rate (20-30%) was, to him, a success.

“I figured that if a small percentage of the field did produce, I could eventually make the rest of the acreage do just as well. My neighbors would never have been satisfied with a field like that . . . but I just viewed the “mistake” as a hint or a lesson. One of the most important discoveries I made in those early years was that to succeed at natural farming, you have to get rid of your expectations. Such “products” of the mind are often incorrect or unrealistic . . . and can lead you to think you’ve made a mistake if they’re not met.”

Mother Earth News interview, 1982

Another aspect of “do nothing” farming that Fukuoka stresses is the lack of dramatic changes. His crop’s output rose steadily over time, eventually meaning he could successfully grow rice all through summer without the need for ploughing or flooding his fields.

SO WHY ISN’T THE WHOLE WORLD GROWING CROPS THIS WAY?

While small groups of people around the world follow Fukuoka’s methods, he believes it hasn’t caught on large-scale for several reasons.

Firstly, he says it is because “do nothing” farming is incredibly challenging, because a farmer must grow his crops differently every year, depending on the weather, insect populations, the soil condition of the soil and other natural aspects. Because conditions change all the time, the farmer can’t use pre-conceived plans or formulas. It requires being in the “present” all the time, something that is very difficult for most people.

The other problem is that this all takes time and it is very hard financially and otherwise to wait for soil condition to improve. It is much easier to throw a lot of chemicals at it and get instant “results”.

Fukuoka died in 2008 at the age of 95.

The One-Straw Revolution

By Masanobu Fukuoka (1978)

This book is now considered a classic sustainable farming, outlining Fukuoka’s philosophy rather than step-by-step methods on what to do. It is inspiring, thought-provoking and a real gem for anyone interested in permaculture, even decades after it was written. His other books include The Natural Way of Farming and The Road Back to Nature.