North Canterbury llama farmer Judy Webby’s hunt for the real llamas of New Zealand

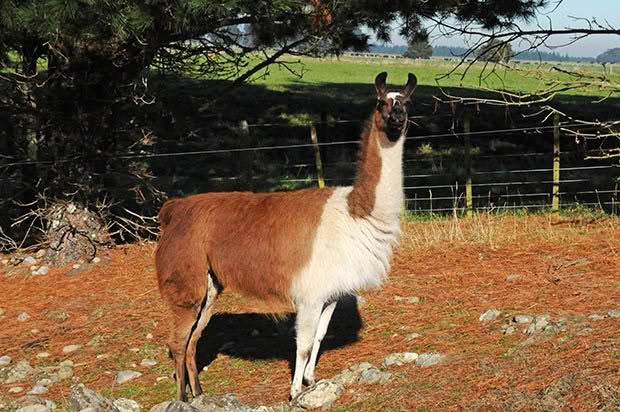

Ricardo De Llanos (Rici to his friends) is one of only 10 verified purebred llamas in NZ. To Judy’s delight, he took out Champion Sire at the 2016 Canterbury Show.

This llama farmer is so dedicated to her quest to find and save the real llamas of New Zealand, she is making a life-changing move to a new home on a new island.

Words: Nadene Hall Photos:Judy Webby

Judy Webby loves her llamas so much, she’s moving islands. She jokes her family has pondered staging an intervention.

“It is very hard to explain and basically you can’t because it’s a passion. I think passion and addiction start to get merged together quite easily.”

The sale of Judy’s suburban home in Manakau will get her a lifestyle block in North Canterbury. “It is a big step, to say ‘no, this is not good for my llamas, I don’t have enough room, I’m worried about facial eczema, we’re all going to go and do something else.’”

Her love for llamas began in the 1980s when the professional photographer was asked to work on a brochure which included alpacas and llamas.

“I was just so impressed with these magnificent creatures, but at that stage there weren’t many of them and they weren’t affordable.”

Judy and Monte.

It was almost 20 years before Judy could take consider camelids. Even then, she did extensive research and kept an open mind on what was the right species for her.

“I had to have the right land and the facilities. I think I joined the Llama Association about 2005 and I gathered information and thought about it.

“When I finally decided I was in a position to buy some camelids, by that stage I’d got a bit confused by llamas and alpacas. I went down and visited a farmer who actually had both for sale. Of course, I took a whole lot of photos. I came home and 70% of my photos were of llamas and only 30% of alpacas. That was telling me something.”

Her first llamas were three geldings that were being rehomed by a zoo.

“I got the three boys and we looked at each other in a fair amount of bemusement for quite a while. Then I thought ‘ok, I’m starting to get the hang of these things, I am going to be able to live with llamas’.

Angelique, a new and potentially exciting find for the llama hunters.

“It’s their personality. (Llamas and alpacas) are both camelids and there’s a degree of similarity. It’s just to me the llama seems to have a more forgiving nature. I used to put my big boy in my van and he would sit down and we would go to the beach and we’d go for a walk, he’d get back in and we’d go home. They’re just easier to handle I think.”

Until April, Judy has been running her small herd of llamas on leased land around the corner from her home. It’s a long, narrow strip that borders the main trunk railway line. But by August, Judy and her troupe will have moved to a new block in North Canterbury to 6.5ha (16 acres). The move means she won’t have the same health issues with parasites as she does on the small area she currently farms, and no issues with facial eczema, which llamas (and other camelids) are particularly prone to. She’ll also be nearer to her friend, long-time experienced llama and guanaco breeder Keith Payne, who shares her passion and quest to find purebred llamas.

The two llama farmers are focusing on a breeding programme to create lines of purebred working stock (known as Ccara llama). For Judy, it was clear during her research phase that there were some odd-looking llamas around and they didn’t look like what you’d find on a mountain in Peru.

Monte has level 2 pack certification.

“In New Zealand, llama are classified as a rare breed, there are only about 1500 of them. As I started to gather my stock, I would go to the Canterbury Show and I’d look at these animals and they were all so different. Some looked like alpaca, some looked like the llamas I’d seen in books. I found that over time, even back in ancient times, there has been a certain amount of cross breeding done, either accidentally or intentionally, to put more fleece on llamas or to put more meat on alpacas. So you end up in most cases with the worst of both sides.”

She met Keith on these travels, and they decided to find out just how much true llama there is in the national herd. If their small pool of findings so far is anything to go by, it’s not much.

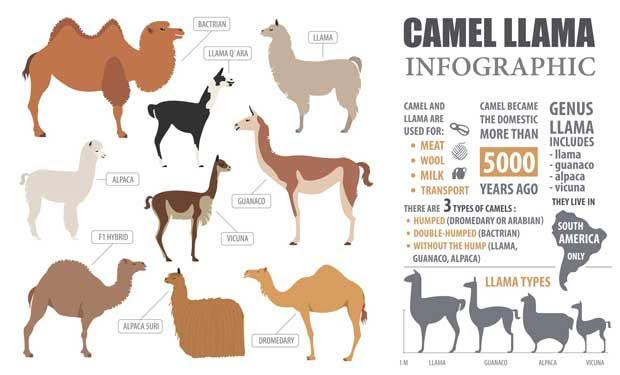

Llamas were first domesticated from wild guanaco about 5000 years ago. They were carefully, selectively bred by humans to be extremely well-tempered pack animals that you could rely on when teetering around the mountainsides of South America moving food and supplies.

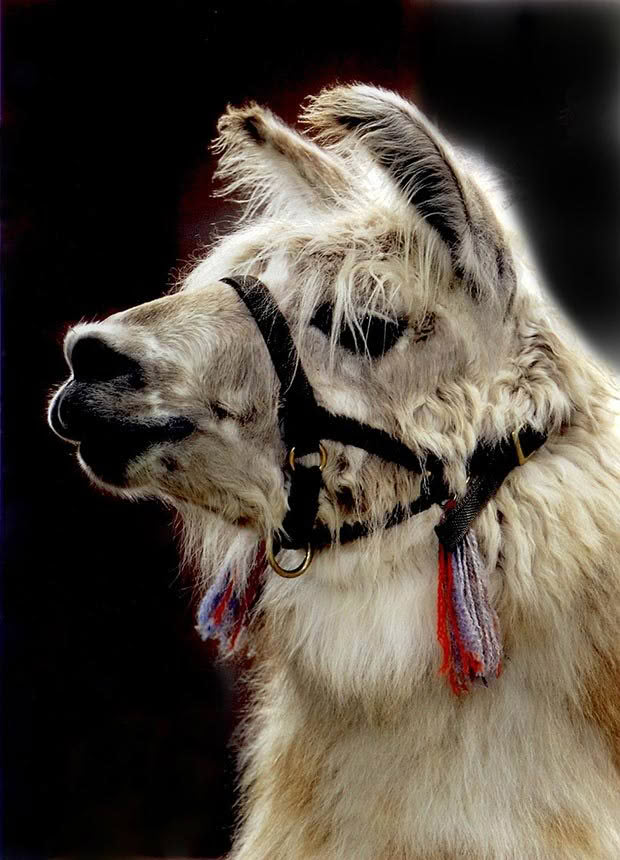

An adult llama is naturally tall (130cm to the shoulder, up to 180cm to the top of the head) and weighs from 130-200kg. Alpaca were domesticated from the wild vicuna for their meat and fine, soft fibre. They’re smaller, standing around 80-90cm at the shoulder, weighing just 70-80kg, and have a very different body shape to the trained eye. Judy has a spiel on the differences that she can now rattle off by heart.

“Alpacas have the pointy ears and llamas have the banana ears. Alpaca have a rounded back, llamas have a straight back. But where you get the hint on your hybridisation is on your hind legs, because the llama still has the hindquarters that can drive it up a hill, whereas the alpaca just ambles around a paddock and hasn’t had to retain that same strength of body.”

DNA testing has meant they now have a better idea of just how much llama is in their llamas.

One of Judy’s female llama.

It’s a very expensive process. They’ve had to carefully pick and choose which animals to test, first by looking at an animal and making a considered judgement on whether its conformation is correct for the llama, especially in its hindquarters and fleece coverage.

“You say to yourself, yes, this looks like a llama, I’m sure it’s a llama, I’m going to spend $1000 to find out if it’s a llama,” says Judy. “Of the ones that were tested, only 25% of them were pure llama. We’ve got 10 that are verified by DNA and there’s another eight that we are waiting for results on.”

The DNA test is limited in what it can do and oddly, it doesn’t test for llama DNA. A blood sample is taken by a vet, then processed in NZ so it can be safely and legally exported to an international lab for genome testing. The llama and its wild counterpart, the guanaco, have the same DNA, while the alpaca was bred from the vicuna. The lab tests for vicuna DNA. A positive result means even if it looks like a llama and climbs a mountain like a llama, if it tests positive for vicuna DNA, it’s not a purebred llama.

‘“The hunt is always there and we have a standing invitation, if anyone thinks they’ve got a purebred llama, they can send photos, if they’re prepared to spend the money on DNA testing all the better. But definitely by looking at the basic images you’ll know whether an animal is worth testing or not.”

It’s important for the breed that they keep their fundamental attributes.

“What we’re doing at the moment is we have DNA-verified males and we are picking the best-looking females, the ones that indicate that they’re pretty close, and putting the purebred males over them. You have to have the verified ones to start with and that’s what been missing.”

Her goal is to breed good llamas and in 2016 her first progeny won best all-round llama at the Canterbury Show. However, it was Monte that first inspired Judy to breed for better animals.

“I noticed he was having trouble with certain obstacles such as walking down hills. That was what started me on the search for information about what makes a llama conformationally correct. Animals that succeed in shows can sometimes be fashionable so I went back to the basics of the guanaco.”

Keith, Judy and other llama enthusiasts have a plan and it’s ambitious in its scope. They want to show people why llamas are a great animal to consider, then sell them the offspring of their purebred animals. They’ll take care of the messy part – the handling of males at breeding time, the pregnancy and birth, and raise the cria (baby) up until weaning – allowing new owners to start with a weaned animal of pure bloodlines.

“We don’t want to wait until they’re worth $20,000. What we want to do is get other people, younger people enthused, make these other animals available to them, and help them as much as we possibly can to increase their own herds. It’s a security (for the breed) as much as anything else.”

Who: Judy Webby

What: Champenoise Llamas

Where: Blythe Valley (6.5ha), 100km north of Christchurch

Web: www.facebook.com/champenoisellamas

A QUICK GUIDE TO CAMELIDS

Vicuna, Vicugna vicugna

Pronounced vie-coo-nah, believed to be the wild parent species of the alpaca.

Alpaca, Vicugna paco

NZ’s most popular camelid, with officially registered animals now numbering over 25,000. They are being bred for their fibre.

Llama, Lama glama

A domesticated pack, fibre and meat animal, rare in NZ and suffering from hybridisation issues from cross-breeding with its near relative, the alpaca. There are two types of llamas, the Ccara (working pack llamas) and Lanudas (fibre llamas).

Guanaco, Lama guanicoe

Pronounced ‘gwah-nar-co’. Native to the mountains of Peru, the wild parent species of the domesticated llama, with only 500 believed to be outside South America, mostly in zoos.

4 REASONS JUDY THINKS LLAMAS ARE BETTER THAN ALPACAS & SHEEP

A mother and cria.

They are respectful

Judy has farmed sheep for almost 30 years, but has found they aren’t respectful of personal space. That can be a problem if you’re a bit more rickety than you used to be.

“Initially I bred sheep but they started to beat me up a bit. If a sheep wants to go to a certain part of a paddock or a yard and you’re in the way, they’ll go through you and it hurts.

“A llama has a natural personal space of about a metre and a half and they will actually go to a great deal of trouble not to invade your personal space. They are just so much safer to have around.”

They have 5000 years of good-tempered breeding behind them

In South America, a good llama is your best friend. A bad llama is dinner.

“If they were nasty and unpleasant then they were into the cooking pot that very night, so the selection for temperament happened with the llama where it didn’t to the same degree with the alpaca. If I get kicked, it’s by one of the alpacas, not the llamas.”

They’re much less work

Llamas (and alpacas) do require injections of vitamins A, D and E because their fibre is so thick, it stops the sun getting to their skin.

But the bonus is a purebred llama is self-shedding, and you can comb out its very fine (on average 18 micron) undercoat and use it for spinning or felting.

There’s also very little hoof trimming needed.

“I have some that I never trim, some I trim once a year, and the odd one or two that need a bit more – generally they’re the ones with white feet.

“I find them quite trainable, I’ve trained mine to pick their feet up. That just makes it easier, you don’t want to battle with a big animal.”

They’re very good converters of feed

An adult llama is approximately 1.8 sheep, but even Monte at 180kg is very light on his feet.

“They reckon the impression of a llama’s hoof on the environment is less than the hiker’s boot because they’ve got those soft toes and they don’t make a mess.”

Where it starts to become a problem is that like goats, they don’t gain immunity to parasites.

“They are evolved to go and have a little bit of this and a little bit of that, the odd twig, a variety, so when we confine them and make them eat around their own manure you have problems and that’s where you have to do lots of drenching.”

A llama has a natural personal space of about a metre and a half.

THE OTHER LLAMA FANS OF NZ

Big Ears Llama Ranch

Keith Payne runs a 20ha property in the Blythe Valley, 100km north of Christchurch. He runs one of only three guanaco studs outside of South America (the others are in the UK).

The guanaco is under CITES protection. It’s an international treaty drawn up in 1973 to protect wildlife against over-exploitation, and it means guanaco are now extremely difficult and expensive to source. Keith has bred carefully, using working type (known as Ccara) llama females and DNA-tested guanaco males to ensure the continuation of purebred llama bloodlines.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.