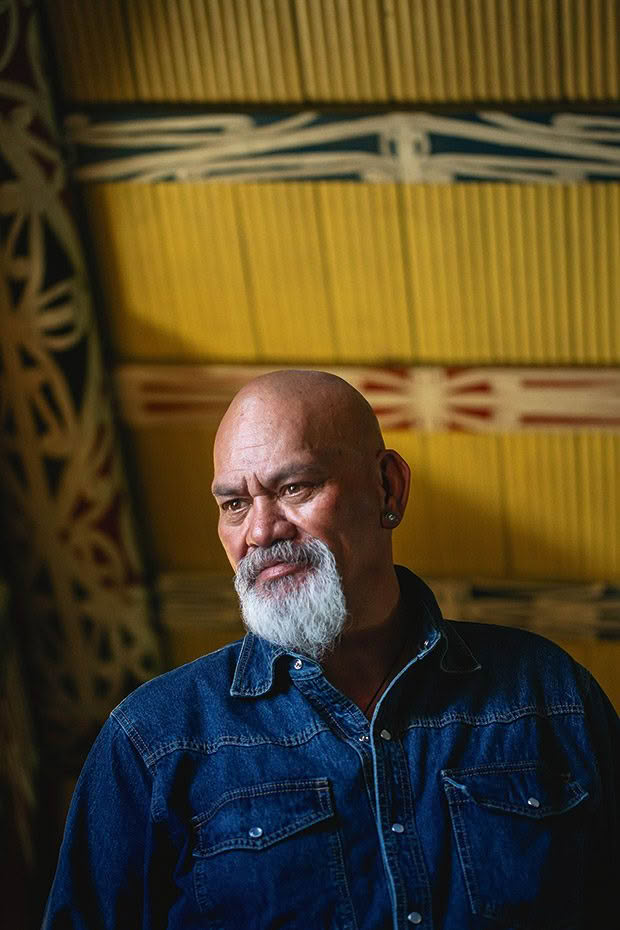

Ngāi Te Rangi chief executive Paora Stanley on a unified, sustainable and thriving future within and beyond Tauranga Moana

Helping a tribe navigate a Treaty of Waitangi settlement can be long and tumultuous, says the chief executive for Tauranga iwi Ngāi Te Rangi, Paora Stanley.

Words: Amokura Panoho Photos: Tessa Chrisp

PEPEHA

Ko Mauao Te Maunga,

Ko Ngāi Te Rangi te iwi,

Ko Tuwhiwhia me Ngāti Tapu ngā hapū.

I am the progeny of our elders from Ngāi Te Rangi and the sub-tribes Tuwhiwhia and Ngāti Tapu.

Paora trained in munitions with the New Zealand Navy, and has worked as a prison officer, health researcher, lecturer and social worker in New Zealand and California. He has also held senior roles as general manager of Te Whānau o Waipareira Trust and executive director for the Listuguj Mi’gmaq Government in Quebec.

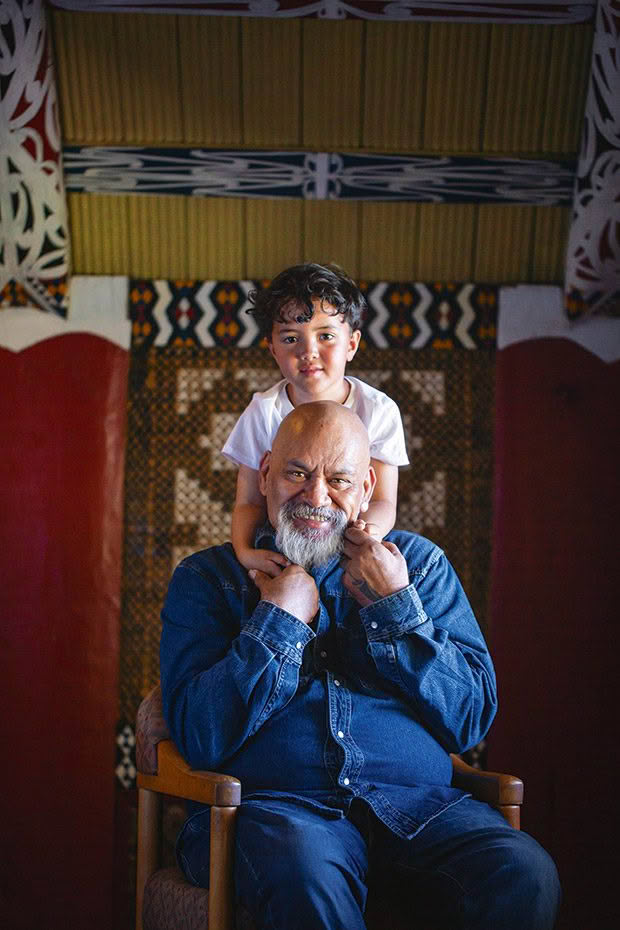

He is a father of five, grandfather of four and married to Laverna from Miawpukek First Nation of Newfoundland.

WHAT GOALS DO YOU HAVE FOR YOUR PEOPLE?

To bed in our tribal plan so that during the next 20 years, our iwi can determine its future as unified, sustainable, thriving, innovative and culturally successful within and beyond Tauranga Moana.

We have signed an agreement in principle but are still some way off from a final settlement, which has been delayed for various reasons, including Covid-19. I continue to travel to many hui (meetings) with our kaumatua (elders), and they often say to me, “We are used to battling away.”

The challenge is to filter those who have a solution for us at a price to those who are genuinely committed to the development and wellbeing of our people — people who want to be part of moving forward to create pride in our identity as Ngāi Te Rangi.

WHAT LIFE LESSONS HAVE YOU LEARNED ALONG THE WAY?

My parents Puti Palmer and Stanley Tutata Kaweroa (from Ngāti Mahuta, Ngāti Korokī Kahukura) were constantly ill during my childhood — my mother with heart problems and my father with tuberculosis.

At times, we ended up living with my mother’s family in Tauranga — where their household would swell to 12 in a two-bedroom house.

Then we moved to West Auckland, where I had a milk run at 11 years old, and became the family’s main breadwinner. Despite our circumstances, I learnt the value of family, the importance of hard work. Being from the school of hard knocks gave me determination and stubbornness to keep going. At 15, I went into the navy, traveled the world and have been on a journey of learning and discovery ever since.

WHAT DID YOU LEARN FROM YOUR EXPERIENCE IN CANADA?

In 2014, my wife Laverna and I were living and working in Beijing when she submitted an application for me to work for her peoples’ nation of Listuguj Mi’gmaq in Quebec as their executive director. (His was the first external appointment in the history of North American First Nations.).

They have significant issues similar to Māori, and my role was to stabilize their businesses valued at CAD$120 million (about NZ$136 million) and increase their effectiveness as a tribal authority.

Paora, with four year-old moko Potahi Stanley Kaweroa inside the meeting house Tapukino at Waikare Marae.

Several times a week, I was in their sweat lodges, where the rocks, called grandfathers, were heated and placed inside an oval hut covered with blankets and skins. The heat is unbearable and requires you to focus on your body and meditate. I learned ceremonial practices; how to build the sweat lodge, how to run it and pour water. And like us the Listuguj Mi’gmaq chant and sing a lot of karakia (traditional prayers).

In Māori culture, a water ceremony relates to whakanoa (to remove tapu/constraints). For me, the lodge experience was like this cleansing ceremony and enabled me to visualize my return to working with my people.

Before I left in 2016, the Listuguj Mi’gmaq gifted me a pipe not generally given to non-natives during their own ceremonies, so I could continue the practices of the sweat lodge when I returned to Aotearoa. This experience taught me patience and focus and still has a significant impact on the way I work today.

WHO HAVE BEEN THE KEY INFLUENCES IN YOUR LIFE?

My mother was a quiet-yet-stubborn influence. Dr Sir Pita Sharples, whom I met when I just left the navy in the early 1980s, had a significant impact on my life. He had started his PhD in anthropology, and I was in awe of him, wishing I could be that brainy. He gave me the hope and aspiration to get educated.

I met John Tamihere in 1991, when I had just finished a teaching degree, and we worked on community projects. From him, I learnt the power and belief in what’s right and what’s important.

From Tukuroirangi Morgan, with whom I dealt in Māori primary healthcare, I learned about staying committed to your people and loyalty.

Syd Jackson, through his union roles, introduced me to another level of exceptional leadership — the courage to lead the fight but also the tenacity to negotiate a resolution.

POST-SETTLEMENT, WHAT ARE THE CHALLENGES AHEAD?

With the impact of Covid-19, the challenge will be how and where we (iwi) invest our money. At this time, 90 per cent of iwi invest within 60 kilometres of their epi-centre. In the Tauranga Moana region, $2 billion a year is generated through Māori horticulture.

Our businesses outperform non-Māori businesses — we are economic legends in our own country, and no one really knows. The real challenge is to corral that economic buying power and make it work structurally for us.

However, we are still servants of our people, and everything we do must be structured as what is relevant as best for them. It can’t just be about making a profit. Trends and data, articulated into bite-sized chunks of information, allows us to plan and keep our people engaged. The knowledge accompanying matakite (vision/foresight more than intuition) is a gift from our tupuna (ancestors) we should value.

The settlement quantum negotiated for Ngāti Te Rangi is $26.5 million, plus interest.

Ngāti Te Rangi are also signatories to the deed entered between the Crown and the Tauranga Moana Iwi Collective in 2015 to receive cultural and commercial redress and enabling legislation.

Paora plans to do his PhD at Helsinki University on native models of negotiation.

MORE HERE

How Jeremy Tātere MacLeod went from a second-language learner to te reo Māori champion

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.