A cycle journey through the Madagascar highlands

Cycling the exotic island of Madagascar provides a lesson in the country’s economy, as well as one in humanity.

Words & photos: Chris Van Ryn

“Bonjour Bonjour. Bonjour.” A group of kids runs after me, thin legs and knobbly knees pumping vigorously. I’m expecting a trip-up, a group implosion. “Bonjour mister,” they shout in chorus. I slow down. They reach me, thrust their cupped hands forward and whoop. “Bonbon mister. Bonbon.” It’s been a hell of a ride. The trail is compacted clay and deeply grooved by rain. I cycle bent at half mast and jump my bike over the indents. My cameras leap and bump from side to side on my back. My shoes and calves are caked in reddish dust. My legs are stiff and my right knee throbs.

I’ve arrived at a remote village in the heart of the Madagascar highlands. The cluster of thatched-roof dwellings are single storey with an ochre-coloured crazed-plaster finish that looks as though it’s been smeared on using the palm of a hand. The air is pungent with wood smoke. Women squat inside dim interiors and cook on small fires of glowing embers. Tendrils of smoke leak from the windows.

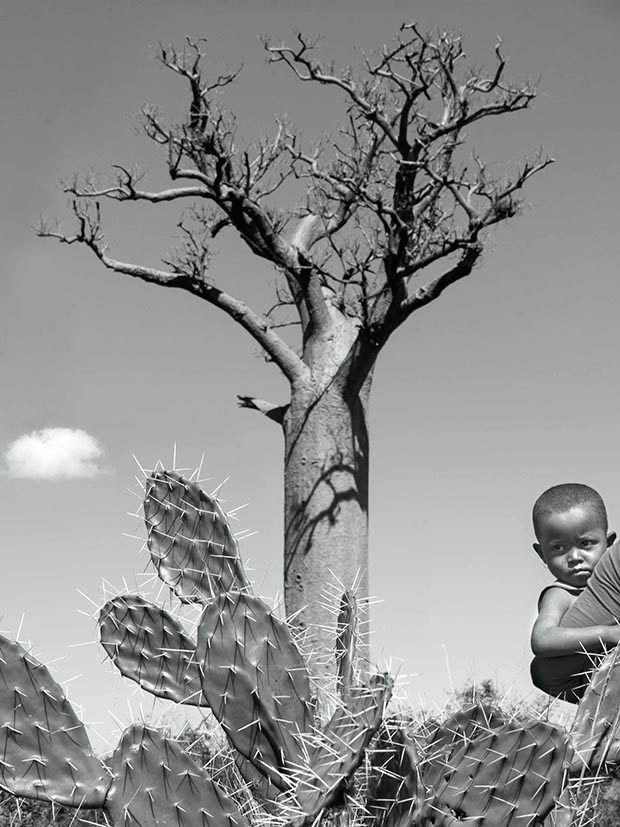

Along the trail I’ve seen rake-thin men, brows oiled with toil, faces dark as worn leather, carrying eucalyptus saplings in loose bundles across their shoulders. This is their fuel – no switch to flick here. The children are no taller than my bicycle saddle. Their eyes are wide and deep and dark and glisten with curiosity. Each nose is snotty, the feet are dusty and their small sausage-like toes with chipped nails are mud-caked. Clothes hang off them the way washing does on a line.

I’m part way through an exhausting 500-kilometre cycle ride, traversing the island from east to west. In the past week I’ve cycled beside sky-scraping granite mountains that made me feel like a rotating speck, alongside wind-sculpted sandstone canyons cross-stitched with layers of time and across expansive plains of waist-high, honey-coloured grass dancing to unseen currents. Ahead of me the hazy horizon is often empty, empty, beyond the occasional arthritic tree reaching out contorted fingers. Cycling alone, these were moments of thrilling isolation. The wheel rotations provided a rhythmic meditation; the grassy plains filtered gently across my mind and produced a Zen-like tabula rasa.

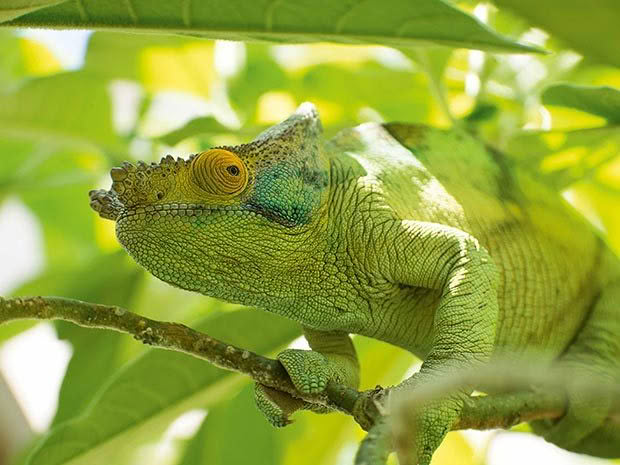

At one stage I’d parked my bicycle beside the trail to watch a chameleon. The bizarre, ancient, colour-changing reptile moved slowly, reaching out, extending its front “fingers” tentatively like a climber testing a cliff face for each handhold before gripping the branch and pulling itself forward. Without haste the motion was repeated with the other leg. And so on. Slow but assured. I got it. Cycling is about the journey. Slow down.

Linger. Breathe… and embrace each new condition. Then the golden canvas vanished. Abruptly. And I’d entered a smouldering landscape drawn in charcoal, eerie and looking like a Hitchcock movie set complete with sooty-coloured crows whining in a disconcerting and remarkably human tone. The villagers, driven by empty stomachs, have slashed and burned trees here to make way for crops.

“Salama… Salama.” I give the children the Malagasy salutation as I get off my bike. I massage my knee. I take my camera – click – then display the image to them. They squeeze into a scrum, jostling for position. The air is heavy in my nostrils, thick with the smell of unwashed bodies. Then there’s an eruption. Howeee. They scream and hoot and laugh, pointing at the camera. But one little boy bursts into tears. I reach over and tousle his bristly hair. “It’s okay,” I say with my smile. I walk to my bike. They follow.

The chant begins again. “Bonbon. Bonbon.” Soon there are requests for money.

Damn. Bloody hell. For the past five days I’ve been hassled and hustled. Tips. Bribes. Bargaining. Straight out rip-offs. I’m a walking ATM. A bit player in an informal economy that coerces money from the haves for the have-nots. Money is a lubricant that makes things happen – enabling a bypass of the long snaking queues at the airport, ensuring the taxi gets me to my hotel, locates my luggage but always leaves a waiter lingering with a look of expectation.

I move past the pleas for lollies and money and cycle onward. There’s a long uphill ahead leading to a mountain top crater lake. My head is down and I’m sucking in deep lungfuls when I catch something out of the corner of my eye. One of the boys has caught up and is trotting alongside me. “Bonjour. Comment allez-vous?” he pants. His trousers are flapping around his legs. He’s wearing a billowing oversized knitted jumper. The sleeves leak over his hands. Play dumb, I think. Then maybe he’ll drop back and leave me alone. “Je ne comprends pas,” I say. “Which country?” he asks. I shrug. “English?”

He tries again. “Mister. Where are you from, Mister? Which country? I live with my mother and brothers and sisters. I go to a privé school.” I’m in no mood for this. “Italian? Come te la passi, Mister? Vivo con mia madre. Vado a una scuola privata…” “Where did you learn Italian?” “You are English.” His name is Patrick. Pat…rrrr…ick with a long rolling r.

Beads of sweat run down my forehead. “Look, stop trying to keep up with me.” I want to sprint off, free myself from any obligation. Stopping is also an option. Just say: “No. No money. Not interested.” But here “no” is water off a duck’s back. I slow down. “Do you have children?” “Much older than you.” “What did they study?” “Languages. You are good with languages.” Patrick shares a brief autobiography – part fact, part fiction.

It’s not so much that he’s bullshitting. Rather, he’s amplifying his need. “I go to a privé school.” We are getting near the crest of the hill when the moment arrives, the reason he’s kept pace with me all the way up the mountain. “Would you like to buy these precious stones? Very good quality.” I glance down at a couple of egg-shaped stones glistening in his palm. “No, no, thanks.” “Very good quality.” “No, really. No. Maybe later. When I come back down.”

Cycling the rugged landscape of Madagascar is a chance to test your skills and endurance. Riding puts you into the scene. a visceral travel experience.

“No, no,” he says. “There are other children at the top. They will want to sell you something. You can buy from me.” A small girl suddenly appears. Her name is Sandra and she wears a faded blue dress and is half Patrick’s height. She too has stones cupped in her hands (very good quality) and goes to a privé school. “But if I buy from you, I can’t buy from Patrick,” I say to her. “It’s okay. We are partners,” she says.

“Really? Well. Perhaps later,” I say. “Promise?” Sandra says. “Promise?” Patrick says.

He offers me his hand. This catches me by surprise. His palm is moist, his grip light.

“Sure, sure,” I say. I head up the mountain track to the crater. On the way down, Patrick and Sandra trot alongside me. A bunch of kids linger behind, like stray dogs. There are two fossils in Patrick’s hand. “How much?” I ask, suddenly crossing a line.

“50,000 ariary.” “What? No way.” I could walk away but the pull to make the transaction is strong now.

“You can bargain,” Sandra chips in. I shake my head. “It’s okay to bargain,” she says. “10,000. I’ll give you 10,000.” “29,000,” Patrick says, without missing a beat. My eyes widen. “Fine. Okay. Here’s 30,000 (just over $10).” I spread the notes out in his small hand. One miniscule contribution to equalizing the disparity in our global economy. “Do you have change?” “No.” I smile. I glance back as I head up the next long hill.

Patrick and Sandra are in the midst of a throng of children. It’s as if Patrick has just scored a goal in a major football game. I feel admiration for this plucky, perceptive, creative, clever, entrepreneurial, tenacious kid. One last look back and I see Patrick and Sandra trotting back towards their village. Side by side.

NOTEBOOK

✱ Air New Zealand has a direct flight to Perth. From there, fly South African Airlines to Johannesburg and on to Antananarivo, the capital of Madagascar.

✱ For currency take euros. Although it’s widely stated that United States dollars can be used, this is far from accurate. Make sure you exchange plenty of euros at the airport for lots of small ariary change. You’ll be parting with plenty of it in the form of tips and bribes. It’s a way of life – best get used to it.

✱ French is the most widely spoken language. A smattering of English can be used in some parts and sign language goes a long way.

✱ Immunisations – there are plenty of jabs you can get (I did) although nothing in particular is required. Travel doctors will consult their guidebooks, which show that Madagascar is a high-risk area for malaria. I barely saw a mosquito but I did take tablets.

✱ Drink only bottled water. Food at restaurants is fairly safe. Risk a case of food poisoning if you eat at roadside stalls.

✱ Try a cycle trip with Crooked Compass (crooked-compass.com), which specializes in off-the-beaten-track travel, well run by local guides. Allow several months of training, including some off-road cycle practice. There are some quite technical aspects on the ride. The longest day covers 95 kilometres at one go. The total distance is 516 kilometres, with approximately 60 kilometres of hikes. The trail, from east to west, ends in the coastal township of Toliara. Accommodation and food are all arranged as part of the tour. Crooked Compass takes care of everything – including bikes. Some people, however, prefer to take their own saddle.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.