Maintaining the land on Blue Duck Station

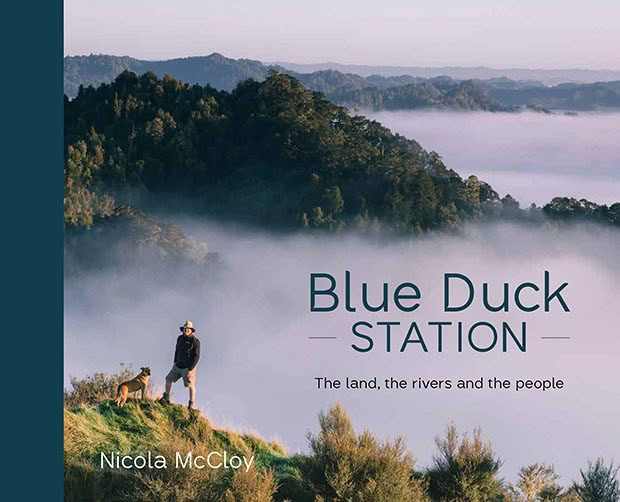

Nicola McCloy’s new book examines daily life on one of the country’s most environmentally significant stations.

Words: Extracted from Blue Duck Station by Nicola McCloy

While Blue Duck Station is renowned for its restaurant, lodges, hunting expeditions, bush safaris, jetboat tours, horse treks, café and hospitality, it’s important to remember that it’s also a very diverse working farm that’s home to a bunch of dedicated people who are so passionate about the place where they live that they’re happy to share it with visitors.

As well as running Blue Duck Station, Dan, Sandy and the team also manage Retaruke Station, and together the properties total about 2800 hectares. On that Dan has 800 beef cattle — Angus cows with some Hereford bulls — and around 6000 sheep. While the bulk of the sheep are Perendale–Romney crosses, Dan’s also experimenting with what’s called an Ultimate sheep.

‘They’ve got a good fleece on them, and we’re trying to grow them so that they don’t develop any dags. They also require minimal drenching. There are also short-tailed ones that don’t need docking, so they’re an animal that’s very light on human intervention.’

Lambing on the station starts in mid-August, which Dan accepts isn’t ideal. ‘We split lambing to spread weather risk. It also means we don’t have to hunt the whole station at once to keep the wild pigs under control. We have a bit of a lack of fences so keeping things apart can be a bit of a challenge here and there!’

Shearing used to happen twice a year, but it’s currently being done on an annual cycle due to the low price of wool. ‘We’re losing money with wool, but I’ll just stick in there a little bit and hope that there’s a little bit of light at the end of the tunnel with the wool prices. It’s a bit of the tradition of the place. It doesn’t provide any income at the moment; in fact, it’s a cost.

‘It might sound impressive to hear that wool prices doubled quite quickly a while back, but that just meant that it went from a dollar a kilo to two dollars! There’s talk of it getting back up to five dollars because there are folks out there paying that for it — places like Big Save Furniture, who are sourcing New Zealand crossbred wool for one of their sofa ranges and offer a guaranteed minimum price, and there’s carpet places buying direct now too. Bremworth have gone back to using 100 per cent New Zealand wool in their carpets. I reckon it’s great to see Kiwi firms like that putting their money where their mouths are and backing Kiwi farmers.

‘Quite a few places are selling wool at a premium because they can tell its story. They’re selling it direct to customers rather than selling it at auction and they get a guaranteed price. I reckon we’ve got a pretty good story so that’s the kind of deal I need! They’re a nice type of sheep — a Romney–Perendale cross — it’s not fine-clothing wool but for socks and things like that, it’s ideal.’

FENCING

Due to the mobile nature of the papa beneath the properties’ pastures, fencing is an ongoing mission — both replacing old fences and putting new ones in. Dan says he’s always analysing whether it’s worth doing fences up ‘because we know they’re going to have to be done up again next year or whether we should just bite the bullet and put in a new fence. It’s a real balancing act.’

There’s been so much flood damage on the place, fencing is ‘like painting the Forth Bridge in Scotland. You get to one end of it and you’ve got to turn around and start again.’

Dan says he’s been really lucky to get New Zealand fencing legend Wayne Newdick, who has won the Silver Spade multiple times at the Golden Pliers fencing championships, down to train his team. ‘He’s a bit of a legend. He makes all his own tools and he understands every aspect of the business. He’s one of the best fencers this country’s ever had and I’ve always got people with a range of skills on the place, and they’re always proud to be able to add fencing to their repertoire of skills. They know that fences they put in aren’t going to move.’

The bulk of the fencing being done involves putting in nine-wire post and batten fences and adding electric wires where they’re needed to keep the cattle back. Solar units have been trialled but they weren’t that successful, ‘but we’re going to get some bigger solar units and run them off mains power where we can as well. Because we’re so big and spread out, there’s a lot of parts of the place where electric just isn’t an option, but a good fence in the right place with a bit of power through it to keep the stock in and the pigs out should last 50 years.’

DIVERSIFICATION

As the soldier settlers found out to their detriment, farming in this hard, rainforest country involves constant battles — against scrub, against erosion, against fences falling, against hillsides washing down and against the natural make-up of the soil — all of which cost money. According to Dan, ‘It’s all throwing good money after bad when the land just wants to be in bush. It’s up to us to work out ways of it being productive while letting it do what it wants. Farming and conservation don’t have to be at loggerheads.’

Returning the land to native bush isn’t as simple as propagating a few seedlings and planting them. The bush has to self-propagate and grow back naturally, but with the right grazing systems and doing a few things naturally, the scrub just bounces back. Luckily, mānuka is one of the first plants that flourishes as the bush begins to regenerate, so the honey allows the Steeles to regenerate the bush ‘and it means we don’t have to intensify to make money’. It hasn’t always been that way though. When Dan started Blue Duck, he had beekeepers tell him that they wouldn’t be able to pay him to put their hives on his land. Since then, the contracts — and the honey prices — have continuously improved. He now has profit-sharing arrangements with two companies — Prolife Foods and Manuka Health — to produce both mānuka and bush honey, such as rewarewa, on Blue Duck Station.

The companies each have 750 hives on the property, and over three years, they have averaged 42,000 kilograms of mānuka honey. However, there are never any guarantees when it comes to the honey yield. There are so many variables along the way — the weather, the flowers, the health of the bees — they all play into the equation.

‘The beekeepers poke the hives up valleys and off accessways. They’re never too far from the roads and tracks. There’s 500 hives on the 7 kilometres between the café and the boundary up the top of the Kaiwhakauka Stream. It’s great mānuka country out there. Then we’ve got about 7 kilometres up the track from the homestead on Retaruke Station where there are quite a lot of hives.’

A lot of people don’t realise that mānuka honey from different parts of the country has different flavour profiles.

‘Some people say they don’t like it because it can be a bit bitter, but the stuff from down here just tastes like good bush honey. It’s very sweet and smooth. It tastes different from mānuka honey from other parts of New Zealand.’

Carbon farming has been another game changer when it comes to regenerating bush. At the time of writing, carbon prices were sitting at just under $90 a tonne with predictions that it will be over $100 before long. This has been beneficial for Dan’s diversification plans. ‘

We’ve got about 300 hectares in the Emissions Trading Scheme and it’s just about all native bush. It doesn’t sequester anywhere near as much carbon as Pinus radiata, but the government have been looking into taking pine out of the permanent forest situation.

‘If they did that, it would be an advantage overall to people like us who can be in the ETS sustainably long-term. I’d like it if we could stay here and earn money out of carbon for doing the right thing.’

Letting the land regenerate into native bush has provided opportunities for the Steeles to diversify with honey, the Emissions Trading Scheme, guided hunting and tourism with people wanting to come and see the blue ducks, ride horses and spend time on the place.

According to Dan, this new way of looking at the land has been beneficial both for the land and for the family. ‘You can have a hard bit of land with four expenses and one income, or you can have a hard bit of land going back into bush and you can have four incomes and one expense. Just because it’s what we’ve always done doesn’t mean that it’s the right thing to do. Diversification is, after all, better for New Zealand than intensification.’