The magic of madness at Matakana Sculptureum

Perched on the hillside overlooking Sculptureum, two figures entitled Call Security by Waiheke artist Richard Wedekind are like slim-lined guardians of the property. The Grants love their real-life animals, including german shepards, Zulu (black), Hachiko (white) and Sheba (brown).

Anthony and Sandra Grant’s curious Matakana playground mixes a love of art with a soupcon of insanity for all to enjoy.

Words: Claire McCall Photos: Tessa Chrisp

It’s a squally Saturday afternoon in mid-winter, and Anthony Grant is doing what he loves. As visitors meander through the Matakana sculpture gardens he has single-mindedly created, he watches their expressions and eavesdrops on conversations. He’s looking for a smile, a laugh, a “wow” moment upon which to hold.

Colour is a critical element that encapsulates Anthony’s joyful take on the art scene. Gigantic pink snails by the Cracking Art Group of Milan are guaranteed to make visitors do the garden smile.

Anthony seems like a man in control. He is, after all, a leading barrister in commercial law who arrives at the office between four and five each morning and writes prolifically on intellectual property and trust disputes. But when he’s here at Sculptureum (a word he coined himself), an unfettered childlike side takes over. The world of litigation and mediation melts away to be replaced by gigantic pink snails, fluffy oversized bunny rabbits and crazy orange hornets.

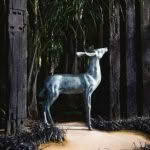

Polar bear by Marti Wong of Rotorua

Anthony and Sandra Grant have spent 12 years developing this 10-hectare property just north of the village. With extensive legal nous underpinning their efforts, the decision to go for it was not rash – but it was a risk. Sandra, also a barrister, got behind her husband’s dream, contributing much of her legal income and co-signing the bank lending to assist them to design and build the gardens and galleries, maintain a small vineyard and incorporate an 80-seater fine dining restaurant. She also provided the encouragement: “I told him he had better get started before he runs out of time,” she says.

A leaping whale by Whanganui artist Jack Marsden Mayer

The couple got together when both their previous marriages had “run their course”. Anthony was a partner at the law firm for which they both worked. She liked his quirkiness. “He drove a burgundy Daimler with cream leather upholstery and pepper-pot alloys and played Thriller on the stereo at high decibels.” He was impressed by her intellect. They moved in together on 21 June 1991 – the winter solstice. Anthony saw it as a significant date, a turnaround point. “He said we had reached the darkest point and from now on things were going to get lighter,” recalls Sandra.

- Japanese-inspired torii tunnel.

- Classical statuary.

- A driftwood elephants.

- The Fishing Boy by Nathan Scott of Canada tries his luck unaware of a lurking crocodile.

- Red meerkats by the Cracking Art Group of Milan.

- A deer (artist unknown) among the mondo grass.

They are a complementary twosome. While Anthony keeps an exemplary wardrobe, colour-coding his shirts, Sandra’s style is more relaxed. When she became step-mum to Anthony’s three boys, it was as confidante rather than disciplinarian. The couple went on to have two boys of their own; both are keen musicians.

“Reuben’s small bedroom is crammed with electronic music gear,” says Sandra. As the olds mull over the day’s events with a glass of their own syrah, band members pop round to join their youngest son in a jazz-fusion jam session.

As a senior commercial and civil litigator, Sandra can match Anthony in the courtroom, but she is also his sartorial sidekick. Today, as he dashes around the gardens handing out almonds to feed the colourful parakeets he sees as avian art, he sports a red hat and clashing pink shirt. Sandra’s garb is the all-black attire of the classic artiste, including a beret. “My great-great-grandfather was French so I’m entitled,” she laughs.

Chico is one of several flemish giant rabbits that live in “Rabbiton” in the Garden of Creative Diversity.

It’s clear that the pair has weathered many storms, including a flood in 2011 when the cottage on the property was inundated by a tide of green mandarins from the neighbouring orchard. Sandra and the teenage boys tried to staunch the watery flow with duvets as Anthony set off into the night to slash down a stand of bamboo that was preventing the deluge from escaping and making the whole situation worse.

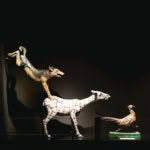

- Mother and baby camel by Dean Patman of Bristol.

- A goat entitled You are what you eat by American Don Charles.

- A sheepdog jumping on a sheep by New Zealander Hannah Kidd.

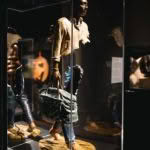

- In the glass case is Antonio by French artist Bruno Catalano known for his sculptures of figures with substantial parts missing.

- The bird on the nest bought from a gallery in Murano, Italy.

- The Grants enjoy the whimsy in the tap with flowing water.

The front paddock where those tall stalks grew along the creek is now the aptly named Garden of Creative Diversity. Here, among others, is a life-size driftwood elephant by Whanganui-based artist Jack Marsden-Mayer, a boy-with-dolphin fountain (a replica of Andrea del Verrocchio’s original work in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence), an overtly sentimental bronze sculpture of a little girl, and a gigantic comb-shaped rock from Puhipuhi in Northland.

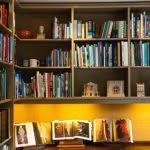

Anthony sports a French gendarme’s hat from his collection. Shelves in the pool room are devoted to glass – his first love – including some by Garry Nash and Australian Tim Shaw.

Anthony abhors the snobbery of the official “art” world. While he loves Chagall, and the collection includes the Belarusian artist’s work (displayed alongside a Matisse and an unsigned Picasso), his curation aims to entertain. He is a sort of Dr Doolittle-meets-Willy Wonka, crafting an experience that is theatrical and mischievous – a mélange of known, unknown, imaginative and real, thoughtful and frivolous. He has written down-to-earth descriptors of the art, brought in flemish giant rabbits to inhabit “Rabbiton” and elegant golden pheasants “because where else would you get to see them?” A lazy river of chocolate might very well be next.

He is an individual who has obviously pondered long and hard about the way we interact with art, but how did this love affair begin? “My father was an insurance manager – and he seemed unhappy,” says Anthony.

Sandra likes to cook when she gets the chance and the kitchen is a generous space for a busy blended family.

“He was into art and bought oils that I thought looked like wallpaper.” Although his mother had some artistic training, she did little to instil this passion in Anthony. “I may have genetically picked up something, but let’s just say I came from a reasonably dysfunctional family.”

Anthony was 16 when his father died and he was sent to live with his mother and her parents in England while he went to study at Bristol University. The day he steeled himself to enter an art shop in Bruton – “I was almost too frightened to go in the door” – and came across some full-scale Rodin works, he was spellbound. “I had never heard of him but I couldn’t believe how wonderfully powerful those sculptures were.”

- Chance, the cat, takes it easy in the master bedroom where an antique gilded corona was cut to the proportions of the bed. The image on the wall is a Chagall Iithograph.

- A Jeff Koons Puppy sits on a chest of drawers flanked by lamps with stands made from balustrades from Bordeaux.

- The couple renovated the open-plan kitchen when they moved in, keeping the oak parquet floors.

- Architectural models of famous buildings (including the entrance to the Victoria & Albert Museum) are on display in the study.

- The couple’s Remuera home has been slightly “emptied” by the sculpture garden project but plenty of artful interest remains. The LED work, on the left of the door to the formal dining room, is by New Zealand artist Gina Jones. It keeps good company with works by Chagall, although Samson (the cat) seems singularly unimpressed.

- A woven basket by Rachel Ravenscroft from England.

- An english bull terrior by Kerry Jameson from England.

- The couple has built up an international collection over the years, including a metal and glass blue-spotted fish by Japanese artist Densaburou Oku.

- The upstairs dining room opens onto a balcony.

- Fountain courtyards which Anthony designed having seen the Islamic gardens in Cordoba, Seville and Grenada.

His own collection started with glass (the living room of the Grants’ Auckland home is bursting with it) and has moved on to embrace, well, pretty much everything in 3D form. “It’s been an organic process,” he says of the way Sculptureum has grown. As lawyers, the pair was pedantic when dotting the “i”s and crossing the “t”s on the paperwork, but such diligence at times dissolved in the face of issues that crop up in design-and-build territory. The restaurant morphed into a far bigger space than envisaged; some works proved unsuitable for outdoor display as colours became cloudy and dull while “treated” metal pieces turned to rust. Many hundreds of palms have been lost to frost and to an unstable root structure.

In singular pursuit, the couple has ploughed a considerable fortune into the venture, going without a proper overseas holiday for 10 years. “It has been a huge financial burden,” says Anthony, almost jovially. “But I wanted to create a place that would inspire people. And I will find a way to make it work.” The $49 entrance fee, he says, is meant to keep the experience uncrowded.

With so many ideas he still wishes to unleash, Anthony sleeps little, works a lot. He appears as a man possessed – a barrister with the soul of a rebel. A series of quotations displayed in the gardens includes one by Banksy who lambasts the art establishment, and several from Steve Jobs, whom Anthony views as something of an unconventional hero. He no doubt relates to the 1997 Apple advert where Jobs said: “The people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world are the ones who do.”

As a commercial endeavour, it remains to be seen whether Sculptureum will soar spectacularly or crash and burn. The venture may not change the world but one thing’s for certain – it has already transformed the lives of its co-creators.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.