Lynda Hallinan’s green-fingered journey began with a few discounted roses and some English lavender

Lynda cuts an heirloom variety dahlia called ‘Preference’ in her cottage garden.

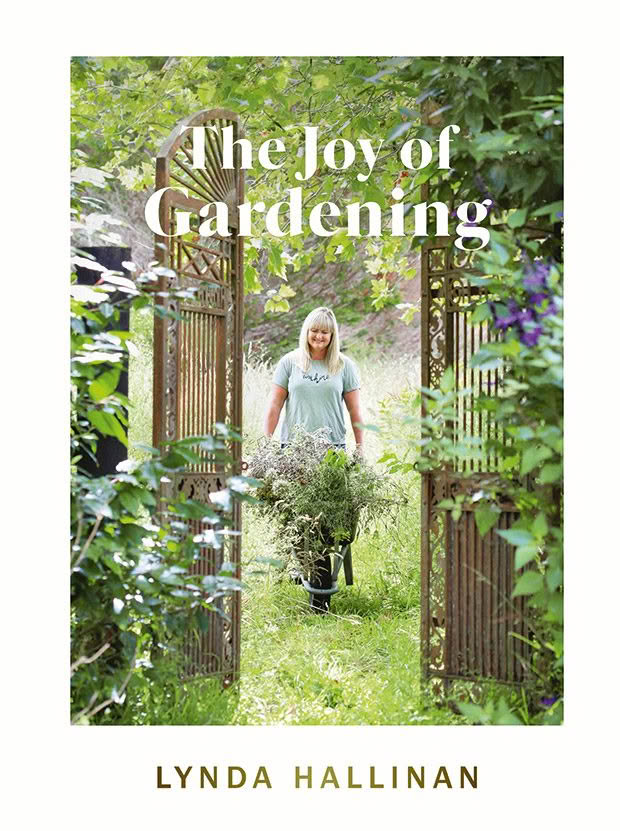

In her new book, The Joy of Gardening, Lynda Hallinan recalls how it nearly didn’t happen to her — the joy of gardening, that is.

Words: Lynda Hallinan Photos: Sally Tagg

At the end of 2020, I gave my garden a thoroughly good soak, shoveled out a truckload of mulch, dead-headed the dahlias and rabbit-fenced my new rose garden. Then I locked the front gate behind me and took my family to the beach for a month.

For the first time in many years, I had decided not to open my country garden at Foggydale Farm, in the foothills of the Hunua Ranges southeast of Auckland, for any summer events or garden festivals. There was no need to stay at home, lugging the hose around parched plants and panicking over page-long to-do lists. Instead, I packed my two sons and our two dogs into the car and set off for the Coromandel Peninsula, where we stayed for most of the school holidays.

Sitting with a group of friends on Ocean Beach at Tairua one afternoon, nattering about nothing in particular, one of them — a psychologist who runs mindfulness clinics for corporates and carers — asked me what I like about gardening. “Can you sum it up in a single sentence?” she asked.

I’m rarely lost for words, but her casual question caught me on the hop. What is it about gardening that appeals to me? Why have I spent two-thirds of my life sowing, growing, mowing, pruning, raking, staking, and creating gardens when I could have whiled away my leisure time writing angsty poetry?

The current darling of the dinnerplate dahlia scene, ‘Café au Lait’ has enormous blooms much loved for summer bridal bouquets. Lynda displays their huge heads in old preserving jars and bottles.

I could have played a sport, learnt the guitar, stitched a quilt or read every word of Marcel Proust’s wordy tome À la Recherche du Temps Perdu (Remembrance of Things Past), having first gained fluency in French, or indeed any second language other than botanical Latin.

The best answer I could muster on the fly was this: there isn’t a single thing I don’t like about gardening, aside from wretched hay fever, which forces me to knock back antihistamines from spring until autumn.

I love gardening, but I’m no hippy-dippy plant whisperer. I wasn’t born with green thumbs, and I don’t believe that anyone else is either. If you think that some are genetically blessed with an ability to commune with nature, then you must also acknowledge the flipside: some people must be gardening’s Grim Reapers, unable to keep anything alive.

This is patently untrue, as on any given day, you’ll find me successfully nurturing some plants while killing others, sometimes wilfully but more often through neglect or misguided optimism about the survival rates of rare species.

The back wall of Lynda’s outdoor potting nook — and houseplant rejuvenation station — gets an annual makeover with washable vinyl wallpaper. “It only takes a single roll to give it a new look,” she says.

I grew up in the thick of the countryside, surrounded by wild landscapes and tame cows. My parents were dairy farmers in Onewhero, a small rural settlement near Port Waikato, and my sister Brenda and I spent our childhood outdoors. We were always building huts in the bush, damming culverts and roaming the roadside in a bid to keep our distance from

Mum and Dad, lest we be given a job grubbing thistles or hosing down the cowshed.

When I left school, I studied journalism in Auckland. To pay my fees, I’d return to the farm each summer to milk the cows with Brenda while our parents were out on the briny. During one break, a local plant nursery had a clearance sale, and for reasons I’ll never fully fathom — was it boredom or fate? — I popped in and bought a few roses and some English lavender.

I dug over a corner of our front lawn and bedded them in as a surprise for my mother, but when they bloomed, so did my desire to plant more. In the months that followed, I rapidly amassed a hodgepodge collection of potted plants and gardening encyclopaedias. Every Friday night while my university mates went nightclubbing with fake IDs, I’d stay home to watch Maggie’s Garden Show and pore over the latest Martha Stewart Living magazine (from the library, as my student allowance didn’t stretch to air-freighted periodicals).

After graduation, I landed a job as a regional radio journalist in Gisborne, where the temperate climate and sandy loam was to my liking, even if the transition to adult life wasn’t. “I go to work, come home, go to bed, get up, go to work,” I complained in a letter to my grandmother in 1996. “But there’s one positive thing: I have managed to grow really big capsicums here.”

In spring, there is no skill to arranging flowers, says Lynda. Just bung what you grow in vintage jugs. Her vintage Tēmuka Pottery jugs are crammed with gladiolus ‘Mon Amour’, scabiosa, verbena, cosmos, foxgloves, Orlaya grandiflora, Ammi majus and the miniature roses ‘Apricot Twist’, ‘Waterlily’ and ‘Lucky Charm’.

My reporting career later took me back to Auckland, to the Independent Radio News network, where I worked 4am to midday or 4pm to midnight shifts in the newsroom, leaving my mornings or afternoons gleefully free to potter in the flower beds I magicked up outside my poky bedsit.

I didn’t recognize it at the time, but the bright yellow ‘Friesia’ roses, heartsease pansies and ‘Sweet 100’ cherry tomatoes I nurtured at my doorstep were an antidote to the treadmill of trauma I was exposed to at work.

Radio journalism relies on a diet of crime, natural disasters and human tragedy; rarely does anything joyful follow the pips at the top of each hour. Our newsroom mantra when putting together bulletins? “If it bleeds, it leads.”

I really wasn’t cut out for the worst aspects of this job, from cold-calling the grieving to bearing witness to the depths of criminal depravity — the senseless bashings, beatings, stabbings and sexual violence — that I reported on from the High Court media bench. My childhood fear of the dark returned, only this time, the monsters in my nightmares had names, faces and rap sheets. I couldn’t go to sleep without double-checking that I had locked all the doors and windows.

The view from the window at Lynda’s writing desk. “Knowing that I’d be seeing a lot of this garden while writing my book, I stocked it with my favourite things: parsley and new potatoes, rocket and green beans, purple echinaceas and pink zinnias, sweet william and scented sweet peas, and a row of blonde bombshell ‘Café au Lait’ dahlias with dinnerplate blooms of faded beige.”

Being constantly in a state of heightened fear is no way to live, so I’ll be forever grateful to former New Zealand Gardener editor Pamela McGeorge, who quite unexpectedly offered me a job as her assistant in 1998, enabling me to trade hard news for a gentler career as a garden writer.

Over the past 20 years, I’ve edited gardening magazines, authored books, fronted television shows, written hundreds of newspaper columns and answered thousands of radio talkback questions, most of which begin with “How do I kill . . .?”

I could have filled this book with handy hints, expert tips and step-by-step instructions to improve your gardening skills, but no one likes a know-it-all. Pleasure comes from discovery, not knowledge.

Traditionally, gardening books and magazines have focused on work — what needs doing this season and how to do it — rather than play. However, since the first Covid-19 lockdown, I’ve started to wonder why we create so much work for ourselves by trying to impose our will on the natural world when the real joy of a garden comes not from working on it but from simply being in it.

I started gardening when I was 18, and I can honestly say that it has brought me nothing but pleasure, personally and professionally. I love it all, from the dreaming and scheming to the planning, plotting and purchasing. When I’m making a garden, I enjoy the process as much as I do the result, even when it hurts all over, as it increasingly does in middle age.

My garden is a joyous place, but it’s also where I turn when I’m sad, worried, frustrated, hurt or angry. My garden allows me to live in the moment, to embrace seasonal change with anticipation rather than any anxiety. It connects me to people

I love, people I have lost, and people I never knew. It is a sanctuary from the stresses of modern life — from parenting to publishing deadlines — and it nourishes me both physically and spiritually.

I’m a better person for being a gardener, and I reckon that anyone who finds joy in sowing a seed, striking a cutting, planting a tree, or managing to keep a maidenhair fern alive in their bathroom for more than a month is a better person for it, too.

SPARKING JOY

Of all the creative endeavours I’ve had a crack at in my life, from pottery to guitar playing, gardening is the only one that has stuck. I still put off jobs I don’t want to do — pruning vicious roses, weeding paths — but as soon as I get going, it opens the floodgates for a rush of feel-good dopamine. This pattern of mental reward and reinforcement reminds me how much I enjoy working in my garden, making me more likely to do it again.

Hobbies make us feel good on multiple fronts, according to neuroscience professor Ciara McCabe of the University of Reading, because they provide “a sense of purpose, physical activity, a shared interest, a route to belonging” as well as being a useful non-medical intervention for depressive anhedonia — the loss of interest in activities that ordinarily bring pleasure.

“Part of the allure of a garden lies in the truth that we are forever learning, and do not have things all our own way,” wrote 1960s South Island gardening columnist Cicely Wylie, whose monthly Let’s Do Some Gardening dispatches appeared between Graham Kerr’s recipes and the practical patterns in New Zealand Woman magazine. At the age of four, Cicely demanded a garden plot where, according to her biography, “lovingly, she planted an assortment of hen feathers and in vain waited for her first crop — of chickens”.

Sixty years later, in her memoir A Garden at My Door, she described gardening as “compensation for growing older, for as long as we have strength to pull a weed, or sow a seed, there is no need for boredom or loneliness. We are never too old to marvel at the opening of a flower.”

We are never too old — or too young — to marvel at the names of those flowers, either. As a toddler, my elder son Lucas was my constant companion in the garden, shadowing my every movement, often in reverse. (I’d plant a seedling; he’d pull it out.) I taught him so many plant names that, as a preschooler, he was nearly as fluent in botanical Latin as English.

On a family visit to Ōhinetahi, I couldn’t tell who was more impressed — me or Sir Miles Warren’s head gardener — when, at two and a half, Lucas tottered into a border of perennial coneflowers and exclaimed, ‘Echinacea purpurea!’

Learning a new language, reading, meditating, exercising: in a garden, you can do all these brain-building activities at once.

Extracted from The Joy of Gardening by Lynda Hallinan, published by Allen & Unwin, RRP$45. Available from 2 November, 2022.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.