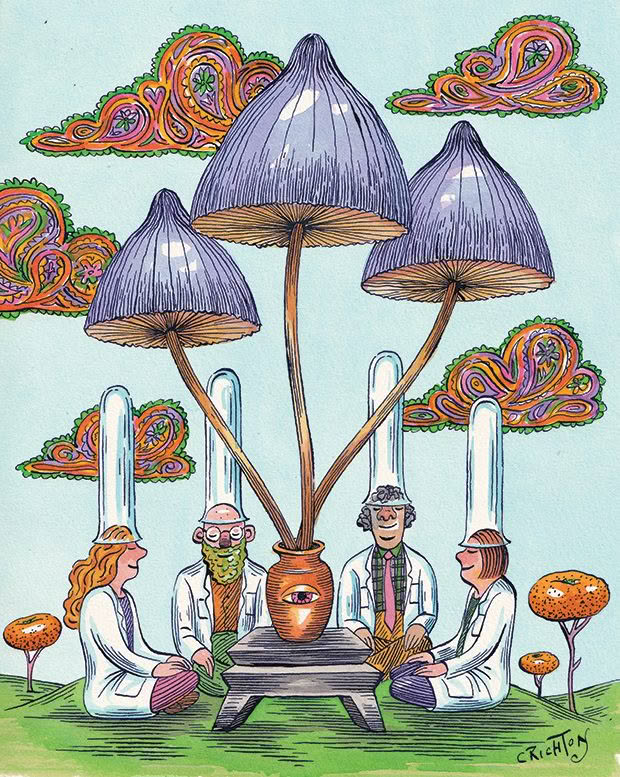

Lucy in the sky with mushrooms: The science behind the benefits of psychedelics

A favourable spotlight is being shone on psychedelic substances after decades of suppression. Why?

Words: Dr Roderick Mulgan

Read more from Dr Mulgan and learn about supporting your health with LifeGuard supplements on the website.

Picture yourself in a boat on a river with tangerine trees and marmalade skies. You might do so if you have a vivid imagination. You might also do so if you had some chemical help, which John Lennon undoubtedly did writing that anthem of acid-drenched dreams in the 1960s when artificial hallucinations were de rigour for creative, free-thinking people.

Then the 1970s happened, the hippies got mortgages and Vietnam draft papers, and psychedelics like lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and psilocybin (the one in magic mushrooms) were banned. It was an unexpected move, which closed down promising lines of research, and is still blamed by some commentators as official overreaction to the threat of counterculture, not any true potential for harm.

Contrary to common assumptions, credible authorities do not lump psychedelics in with harmful recreational drugs. David Nutt is a professor of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London and a leading commentator on drug laws, and he likes to point out that mushrooms and LSD cause no physical harm and are not addictive. He advised the British government on drug policy until he was sacked for pointing out that ecstasy kills fewer people than horseriding. In his view, psychedelics are “among the safest drugs we know of”.

A major review of LSD studies done over the past 25 years, albeit with a relatively small number of people, concluded that “in medical settings, no complications…. were observed”. It is a theme with deep implications. There is no solid reason to explain why tobacco and alcohol are legal, and marijuana is not. The legal status of psychedelics likewise seems to have more to do with moral outrage than a graduated approach to risk. Against this background, perhaps another look is called for, and many are sharpening their focus.

Exhibit A is therapeutics. The authorities may not be moved by people who enjoy an afternoon watching the sunlight turn chartreuse and the carpet billow like the sea, but they have to pay attention when disease is in play. Depression is the planet’s biggest psychiatric condition, and numerous drugs have been created to alleviate it, most of which work modestly well at best.

So psilocybin and LSD are back in the laboratory, and numerous trials demonstrate they not only lift the blues, they work on some of the most difficult resistant cases and have the remarkable property of giving sustained relief with just one or two doses. Nothing conventional comes close.

A small front in the pushback has been opened up in the United States by religious freedom arguments, coupled with the modern mindset of recognising indigenous rights and winding back the levelling hand of the dominant culture.

In 2006, the United States Supreme Court ruled a spiritual sect that uses a hallucinogenic tea called ayahuasca could triumph over drug restriction laws; likewise, Native Americans can legally consume hallucinogenic mescaline from the peyote cactus, as their forebears, who considered it a sacrament, did back to prehistory.

The field is not large, but devotees claiming their experiences are spiritual and therefore protected are likely to continue challenging the system and widening the field of lawful consumption.

Why it works is not clear. Psychedelics appear to stimulate neurotransmitters in the brain, which are the chemicals nerves use to talk to each other. Brain scans show affected brains turning chaotic, with different regions talking to each other more than usual. Nor is it clear why plants provide such wonder in the first place. The leading theory is that they are trying to make browsing insects hallucinate and desist from eating them. Human bliss is just a happy byproduct.

So should we take bliss when plants so kindly hold it out? Recreation is the true battleground between libertarian and authoritarian perspectives, and the libertarians are getting some runs on the board. The review of LSD referred to above concluded that “LSD mainly induced a blissful state”. It caused increased feelings of wellbeing, happiness, closeness to others, openness and trust. It increased the emotional response to music, changed perceptions and induced “positively experienced derealisation and depersonalisation”.

Whether we should be turning our backs on such life-enhancing options is becoming a legitimate question. Serious modern authors are writing about the happier, richer lives that might open up to us if regulated access to these experiences became possible.

Sometimes the trip can be profound, particularly when it involves an audience with a higher being, an “ultimate reality”, an entity that is “conscious, benevolent, intelligent, sacred, eternal and

all-knowing”, according to one study. God, in other words.

We, who haven’t been there, say meeting God is a drug-induced hallucination, but the people who have done it say they felt something as real as the ground and the wind and the trees. The ground and wind and trees, as we experience them day to day, are also products of chemicals pinging off each other in our brains, so the distinction between the real and the hallucinogenic is not as clear as we might like. Who can say which set of chemicals is more authentic? Deep philosophical rabbit holes open up.

Which is not to say mind-bending experiences are there for the taking. Enthusiasts seeking their high from mushrooms can easily consume the wrong type and the wrong amount. Even when the dose is professionally pronounced to be safe, thinking you can fly out the window might not be, and laboratory settings, where our information comes from, are always supervised.

Then there is the law. For all that can be said in their favour, and the ongoing march of decriminalisation in various places overseas, these substances remain illegal here. Until that changes, you cannot meet the girl with kaleidoscope eyes and keep your career prospects and overseas travel rights. But maybe change is coming. Moral outrage is not as certain as it used to be.

REFERENCES

1. theguardian.com/books/2023/jun/15/psychedelics-by-david-nutt-review-hope-or-hype.

2. Nutt, David J, Drugs — Without the hot air: minimising the harms of legal and illegal drugs. Cambridge: UIT, 2012.

3. Liechti, M (2017). Modern Clinical Research on LSD. Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(11), 2114-2127.

4. Madras, B (2022). Psilocybin in Treatment-Resistant Depression, The New England Journal of Medicine, 387(18), 1708-1709.

5. Pollan, M, How to change your mind. Penguin Press, 4 June 2019, p28.

6. Liechti, M (2017). Modern Clinical Research on LSD, Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(11), 2114-2127.

7. Pollan, M, How to change your mind. Penguin Press, 4 June 2019. 8 Griffiths R, Hurwitz E, Davis A, Johnson M, Jesse R, Survey of subjective “God encounter experiences”: Comparisons among naturally occurring experiences and those occasioned by the classic psychedelics psilocybin, LSD, ayahuasca, or DMT. PLoS One (2019) Apr 23;14(4):e0214377.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.