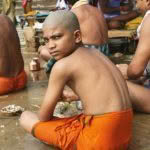

Lessons learnt in silent meditation in India

Rickshaws (pulled, pedalled or motorized) are many a poor man’s livelihood.

A long ride on a spine-cracking rickshaw and ten days of excruciating, immobile silence lead to a place of slow-and-surprising recognition.

Words and Photos: Chris Van Ryn

It begins with a rickshaw ride on an exasperated whingeing vehicle which belches and farts blue-grey soot and smells like a lawnmower. The driver is hunched over, thrashing the unresponsive throttle, steering this limping three-wheeler through pounding heat along dry, compacted-dirt paths, away from the frenetic city of cajoling, beckoning hands and wheedling “Please, sirs”.

He wears a loose shirt open to the waist, revealing form-fitting brown skin that profiles each rib. His unkempt midnight hair, glistening with oil, flops over a beaded brow and he reeks of that universal equaliser – body odour – that springs from sweaty armpits, regardless of age or elegance, race or religion, wretchedness or wealth.

Early this morning I hailed his rickshaw. I met his eyes: two fathomless black holes drilled into startling white ellipses. His battered charge with its cracked black-vinyl seat stood alongside a dozen others, competing for my coin, each three-wheeler and owner equally deflated, melancholic and forlorn.

But this is his Rolls Royce. His cash cow. His life-sustaining engine. His name is Lucky.

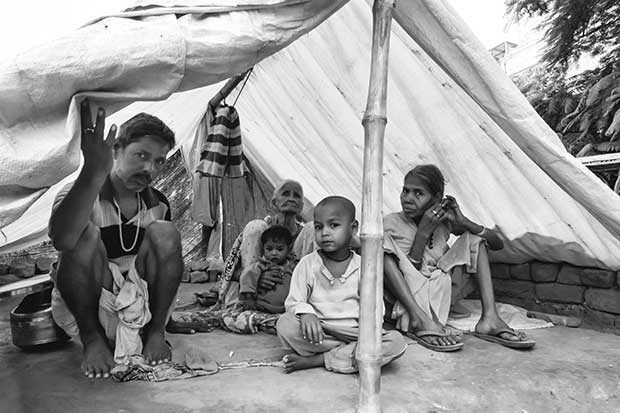

In Varanasi, the homeless share the streets with wandering goats.

We are two gut-jarring hours out of Varanasi, that ancient city of India where every nook and cranny has religious salvation, incense, a goat and desperate, unremitting poverty squeezed into it.

The rickshaw proceeds with a high-pitched recalcitrant whine, weaving around potholes. We come to a ramshackle village, its spirit obviously broken. Everything is wretched. Homes are haphazard impotent assemblages, some at perverse angles. A clutch of scrawny chickens peck dementedly at lifeless mud.

A pant-less girl plays, gunk oozing from one nostril. She is wide-eyed with mouth agape as we pass. Dogs with pointy snouts and protruding ribs watch with languid disinterest. A man slumbers on the ground.

His thick, calloused feet have chipped toenails and soles fractured with a network of fissures: a map of his life. To get a feel for this place, taste the dust that catches in your throat and thickens your tongue, and smell the shit that hovers around the edges.

Lucky pushes on. On the other side of the village, in striking juxtaposition, is a surreal panorama as the road bisects a waving choreography of luscious lime green: field upon field of rice, rolling into the heavy mid-morning heat-haze.

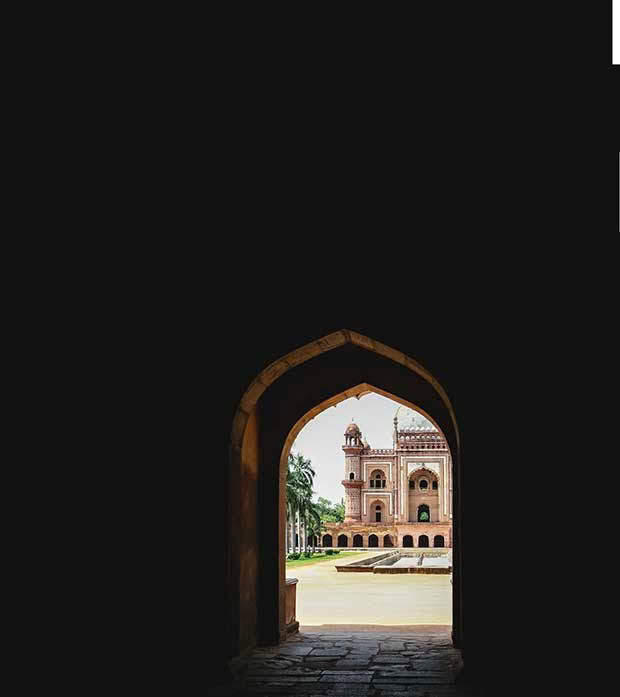

India is a constellation of a million contradictions. Food and festivals flood the senses while beggars’ bellies go empty; temples of sublime beauty, richly adorned, back up against slums of shocking ugliness; opulent gold amulets swing on wrists while eyes are snagged by unfettered poverty; women in face-to-foot burqas walk past erotic ornamentations and priapic carvings; elders’ feet are touched while untouchables are not … and on and on.

Families ask for money near the sacred Ganges river.

Over the last two months I’ve criss-crossed India. When I reached Varanasi, that holiest of holy cities, watching the Ganges sun salutations one grey-toned dawn, I thought: this spiritual centre has 3,000 years of Hindu and Buddhist wisdom – what better place for an epiphany?

And yet, against a backdrop of Varanasi’s human detritus, this seemed a wisdom studded with absurdities: an elephant god with four arms and a swollen tummy (Ganesha) alongside a one-legged, empty-bellied beggar. Lucky is taking me to 10 days of silence, my destination an ashram somewhere in these fields of green.

Places of worship, such as the Shri Kashi Kamkoteshwar Mandir temple, are adorned with statues of the gods.

Through a meditation called Vipassanā, I seek… transcendence, a way to usurp the vicissitudes of life, a journey of self-discovery, where the secret workings of sustainable happiness might be revealed. I dream of turning around and seeing my life with new eyes.

We pass a woman carrying a huge load of branches balanced on her head.

Her face, a piece of well-worn leather, has the countenance of a life of toil. Squatting women with layers of sari bunched between their knees tend the fields using small trowels, shuffling back and forth.

Temples of sublime beauty and exquisite craftsmanship can be seen throughout India; they are a stark contrast to the slum houses where many reside.

In the absence of a motorised plough it’s the small trowel that keeps them employed.

They work until they turn into silhouettes and finally dissolve into shadow.

The ashram comes into view, a bland, utilitarian construction in a post-war communist style of architecture, softened only by the gentle ballet of green surrounding it. The challenge ahead dawns on me. What was I thinking? Not speaking or moving for ten days! I seek lasting happiness but now

The faces and lives of the people are shaped by poverty, culture, religion and the environment.

I panic because it seems I’m on the threshold of pain. When we finally reach the ashram, I haggle with Lucky about payment. I’m being ripped off and now I’ve entered pissed-off mode, my jaw is clenched and things are getting heated.

Lucky’s voice is raised. He paces back and forth, his broad, bare feet kicking up puffs of dust. His stomach tenses inwards, like a greyhound’s, and then… all of a sudden his shoulders slump. He snatches the crumpled notes from my hand and begins his long whine back, in the searing mid-afternoon.

Later, in my room, I feel bad. For Lucky it’s an exhausting six-hour rickshaw ride. For me it’s a few extra rupees. My room is small and austere, made of concrete, with bars on an unglazed window.

Despite living in dire conditions, street kids can be filled with laughter.

Jammed up against one wall is a metal bed with a thin blue vinyl mattress surrounded by a mosquito net. An even smaller adjacent room has a hole for squatting and a plastic bucket for washing. No embellishments, no distractions.

It begins.

Each day at 4am.

With feet wedged under me, I remain statue-still, silent, eyes closed, a self-imposed isolation, with two 15-minute refreshment breaks, resuming the position until 9pm, during which time I’m hijacked by small irritations, swelling with each passing tick: a wrinkle in my sock, at first a caress of cloth, later a branding iron; an itch above my right eye that laughs, then throbs and rants and raves, and another, under my foot which tests my resolve, my mind, my commitment; a drop of moisture, delightful, delicate and translucent, then pregnant-heavy that, freed from its pore, creeps slug-like down my neck, another down my forehead, coming to rest on a hair follicle; stiff knees and backache and tiredness and hunger – an ever-increasing, inescapable malady of tortures exacerbated by observation.

This disabled man with brilliant ingenuity moves his family around in a hand-powered bicycle.

And all the while words reverberate ad nauseam inside my skull: Why am I here? Because. Yes, but ten days? Breathe. You might as well. Do this. Stop thinking. Breathe. Don’t say stop. Say nothing. Just breathe. Don’t say breathe, just breathe. Stupid narcissism. Shit, ten days here. TEN DAYS. Breathe. Let go. Nothing is easy.

I want to be released, to find the world beneath the words. Breathing is my portal to this world. A Möbius strip of breathing.

A makeshift home on the banks of the Ganges.

I begin a slow, silent intake, then a lingering audible exhale, a sigh – white noise upon which I clip my mind to still the monologue, narrowing my awareness to the tendrils of air passing in and out of the nostrils, elated at the discovery of rose perfume that – oh my – reaches me from a garden 20 metres away.

Other scents unfold, hitherto unnoticed; and the element of time and pain drops from consciousness; and the air traverses the trachea, expanding lungs, exiting blood-warm, each outgoing breath an exhalation of mind so that it empties – of noise, of ego, of future and past narratives – so empty that where once there was an identity, now exists a formlessness.

Locals get a wet shave by expert roadside vendors who use old-fashioned honed steel.

And in that void, a new, borderless, hypersensitive being is born, a new mindfulness, a living in and acceptance of the moment, and entering this new-found reality, this buffer against life’s headwinds, this amelioration of suffering, this pathway to happiness, springs Lucky.

Shit. God-damn those bloody rupees. I’ve messed up. Confused the dance steps. The epiphany is a soap bubble. The world beneath the words collides with the world outside. What about Lucky? And the other rickshaw drivers? Or the girl with the snotty nose, or the beggars with amputated limbs who, like a human balustrade, line the colonnade that leads to the Haji Ali Dargah mosque, chanting paisa, paisa, paisa – money, money money?

Present-moment living? Acceptance? Perhaps this is my epiphany.

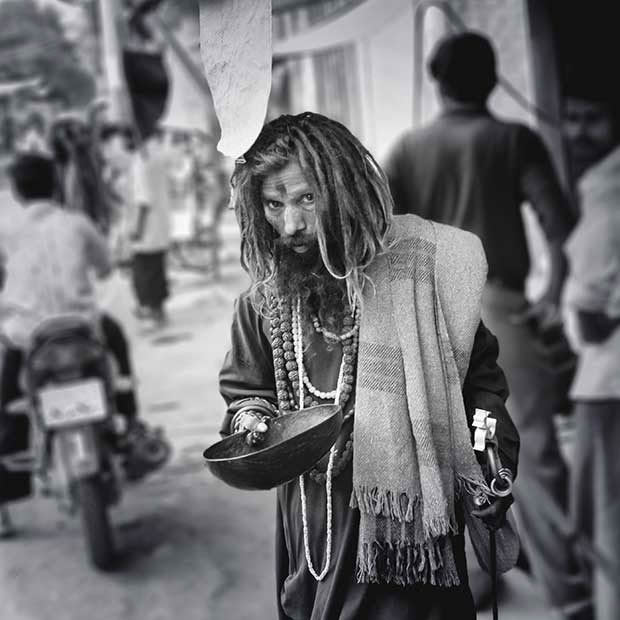

A religious guru will promise salvation for a few rupees.

When I arrive back in Varanasi, I dump my bag on the hotel bed under the whirring fan and, after a salted lassi on the rooftop overlooking the tea-coloured Ganges, that shit-floating carpet for corpses where Brahman bathers anoint their souls with rituals of purification, and where in the distance, following the gentle arc of the waterfront ghats, tendrils of undulating smoke from a cremation drift skywards, I exit the hotel and head past the brightly garbed guru sitting cross-legged with snaking waist-length dreadlocks and turmeric-smeared forehead offering blessings and salvation for a rupee, past the bleating goat complaining about its droppings, past the bleating beggar tapping a tin bowl while others pontificate over his previous life perversions, past the street-barber stropping his steel, giving a once-a-week wet shave – which I’d like after ten days but can’t in case I receive an HIV cut – to the Assi ghat, where the long line of rickshaws wait for rides.

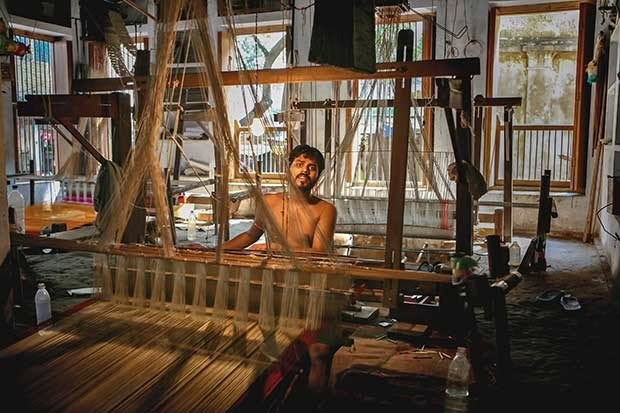

The city has a rich history in textile design; particularly brocade.

I see Lucky, hands behind his head, black holes staring at life’s margins, but before I reach him, other drivers galvanise, ready to hustle a gora for a rupee-ride. I don’t want them to see what I’m doing, so I lean in close.

Lucky lifts his flipper-feet off the handlebars, and I slip him a clutch of cash. “Here,” I say, “take this.” He looks startled. Then shy. Then he smiles, with surprising softness.

He thinks I did it for him. I know I did it for me. I walk away and stand on the ghat and turn around slowly, a full 360 degrees, the sun playing across my face. I see my life through new eyes. Lucky’s eyes. Transcendence.

NOTEBOOK

In a city that is deeply religious, at dawn, or in the evenings, holy festivals are held on the river bank. For the visiting traveler, these are theatrical and empowering sights.

Info on the course:

Vipassana meditation in Varanasi can be booked online with both short and long courses. A ten-day course is recommended but it’s not for the faint-hearted. There is no speaking or looking at others the entire time, so it’s an intense period of isolation, and you sign a contract to state you will stay to the end. There is no charge for the course but a koha is anticipated. Contact the Sarnatah Vipassana Centre.

How to get there:

Singapore and Malaysian Airlines fly between Auckland and Delhi. From Delhi connect to a local airline (IndiGo, Air India or Jet Airways) for a 1.5 hour flight to Varanasi (about $100 and $200 a ticket). Once there, DON’T take a rickshaw. Trust me. Take a taxi or hire a driver instead. Ask Praveen (see below) how to go about it.

Where to stay:

I stayed at Palace on the Ganges, a heritage hotel with a rooftop restaurant that affords a view across to the Ganges. Try the lassis; they are truly divine.

If you need help to find suitable accommodation, I can recommend Praveen Pathak, a fabulous young man who can act as a travel guide, recommend accommodation and find the best restaurant. Mention my name. His WhatsApp number is +91 05321 0764. You’ll need to pay him but he’s well worth it.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.