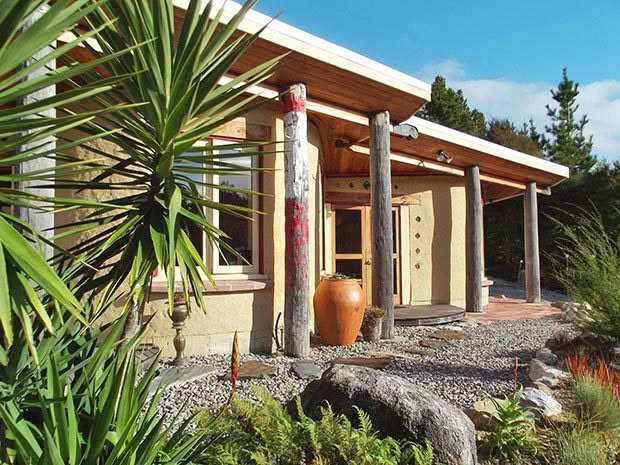

‘Lessons we learned building a cob house’

Buying a bush block, building a cob house, and starting a natural soap business takes huge amounts of energy, enthusiasm and commitment, but this family are thriving on the challenge of being as clean and green as possible in everything they do.

Words and Photos: Fiona Cameron

Kerryn Easterbrook and Phill Thomas love a challenge, and they certainly created quite a few for themselves when they moved to a bush and pine-covered block in Golden Bay 12 years ago.

Their goal was to build their own home in as environmentally-friendly a manner as they could, tackling most of the work themselves.

The result is their very special, eco-friendly, four bedroom cob home, but it has been a huge learning curve.

“We never envisaged it turning out quite like this, it took on a life of its own,” says Kerryn.

“When one of us was feeling overwhelmed by it all, the other was usually feeling positive so we kept each other going.”

They make a good team, an essential element when deciding to build a house together. They drew up the plans, prepared the site and moved into a converted house truck on the property.

The house is carefully sited to get maximum benefit from the sun.

Then came time for extensive research into how they could gain the maximum benefit from passive solar energy. Phill attended a week-long earth building course with local civil engineer Richard Walker. They studied sun charts, but also sun path diagrams which accurately showed the angle of the sun at any given time of the day in the year. From there, they could then work out that 6m was the maximum depth for a room to receive sunshine right to the back wall in winter.

“We made a model of the house using cardboard, complete with cut-out windows, and used a light bulb to work out the sun’s path in winter and summer,” says Kerryn.

The results were then used to design a home that is split level with full depth of eaves, no hallways, and every room facing north to benefit from the winter sun.

Placement of windows was also important because the couple had a different perspective to most other homeowners.

“We put a higher priority on facing the sun rather than the views.”

They chose cob for the building’s structure, something that is still an unusual choice in NZ.

“The earth walls are fundamentally thermal mass, like oven bricks,” says Phill. “They soak up the sun during winter days and release it at night, rather like a night storage heater. Yet on a hot day in summer they keep the house cool.”

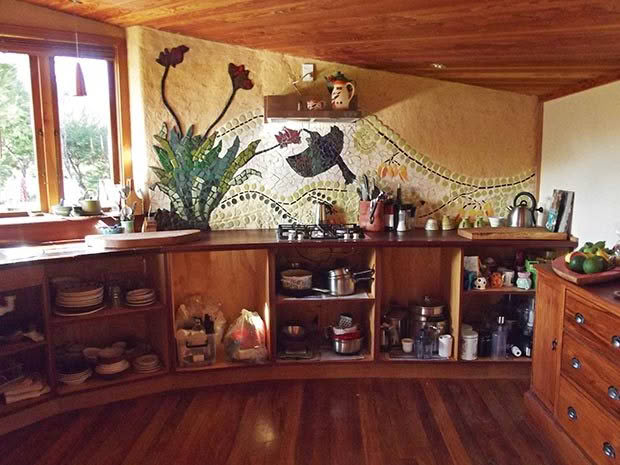

Kerryn in the kitchen.

The clay on site that would make it difficult to create their (now) thriving organic garden, complete with vegetable beds, soft fruit cage and fruit trees, proved a bonus when they decided to build a cob house. Sand and clay were both sourced on their property and mixed with straw, meaning they didn’t require cement. A tractor with rotary hoe was used to turn the mixture as it was too hard to mix by hand.

The floor had to be concrete to support the building (cob is not permitted as a foundation). In the living room, 40mm-thick adobe tiles sit on top of the concrete.

The couple preferred to avoid chemicals in the building process. This was a challenge, even when you have a pine forest to pick and choose from. However, that clay soil turned out to be an advantage again. Because the trees on their block had been very slow to grow in the poor soil, the resulting wood was a winner. Phill has a letter from the Forest Research Institute verifying that heartwood from their pine is the equivalent to H3.2 durability, which allowed it to be used for some parts of the construction work.

Kerryn’s first attempt at mosaic is now a feature wall in the kitchen.

They spent six months cutting and milling the trees, borrowing a mill from a neighbour, and then stacked it to dry. Three weeks after starting work on the house, they were close to running out.

“You need a massive amount of timber to build a house,” says Phill. “We couldn’t cut, mill and dry it fast enough.”

They also found it needed time to season otherwise it would warp, and the work involved with processing it delayed work on the house.

“You also need someone to ‘read’ the trees, to assess accurately what you will be able to use from them as there is so much wastage. We had big ideals at first to mainly use our own timber, but you need to plan years ahead because it takes a year, or more, for stacked timber to dry.”

The concrete floor in the living room is covered in adobe tiles.

But their building consent and therefore their time limit had already been granted. They were forced to purchase milled timber from elsewhere, but the couple were determined to keep it as local and low impact as possible. Douglas fir was sourced from Nelson and used on the ceilings with copper nails. Recycled rimu was bought from an old house that was being demolished and used for some of the finishings. Second-hand jarrah posts originally used as power poles were sourced from Blenheim and make perfect roof supports.

It helped that Kerryn’s father is a builder and would occasionally help out; the only other assistance came from tradesmen who did the plumbing and electrical work.

Kerryn and Phill did everything else themselves. Phill had basic school-learned woodworking skills, but discovered he enjoyed working with wood. He worked out how to do all the joinery for the windows, doors and finishings, and built the cedar windows and the macrocarpa frames they sit in. He learned most of it as he went along but says he did ask for help or advice when he was unsure.

Phill, a self-taught joiner, made all the windows and doors.

Kerryn helped with all aspects of the preparation and building work too. She then turned her crafting skills to the walls, completing her first mosaic in the kitchen, a beautiful design that runs the length of one wall, something she says was a lot of fun.

The back walls of the house are cut into a hillside which allows for the ground to act as a form of insulation. Their huge pantry is built against this back wall making it just like a cellar, perfect for storing food and preserves.

“Even without heating, the house is a constant 15°C in winter,” says Phill. “You don’t get those day/night time temperature fluctuations common in other houses.”

The home is 6m deep, the optimal width that still allows sun to reach the back wall in winter.

Five years after they started, they moved in. The kitchen, living room, bathroom and composting toilet were all done, leaving the upper level bedrooms unfinished. They stuck firmly to their plan to only move in once the lower level was completely finished, and now they’re in a race to have the bedrooms ready for this summer’s guests.

Living so close to Te Waikoropupu Springs – one of the biggest attractions for tourists to Golden Bay is just minutes from their home – is certainly a bonus. They have called their accommodation Sanctuary Springs, and it definitely is.

WHAT IS COB?

Cob is a mix of straw, a sandy soil and often small gravel. The stiff mixture is formed into cob (an old English word for ‘lumps’, eg cobbles, cobblestone) which is then thrown onto the wall and stamped (by foot) or worked into the previous layer to form a wall of almost any shape. It is then usually rendered to give it a smooth surface.

Phill working on one of the bedrooms.

Source: www.earthbuilding.org.nz

Working from home is the ultimate dream for many people but setting up a business can seem so daunting and risky that it remains a fantasy.

Kerryn and Phill both work part-time off-block, but when a friend told them about the soap-making business she was selling, they could see a great opportunity and felt it was a good home business that they could expand while they built their house.

Kerryn has always enjoyed craft making, and she was wondering what she could turn into a business when the opportunity arose. While her knowledge of soap-making was limited, she had already studied essential oils through a correspondence course which proved useful for what has turned out to be Clean Earth Soap.

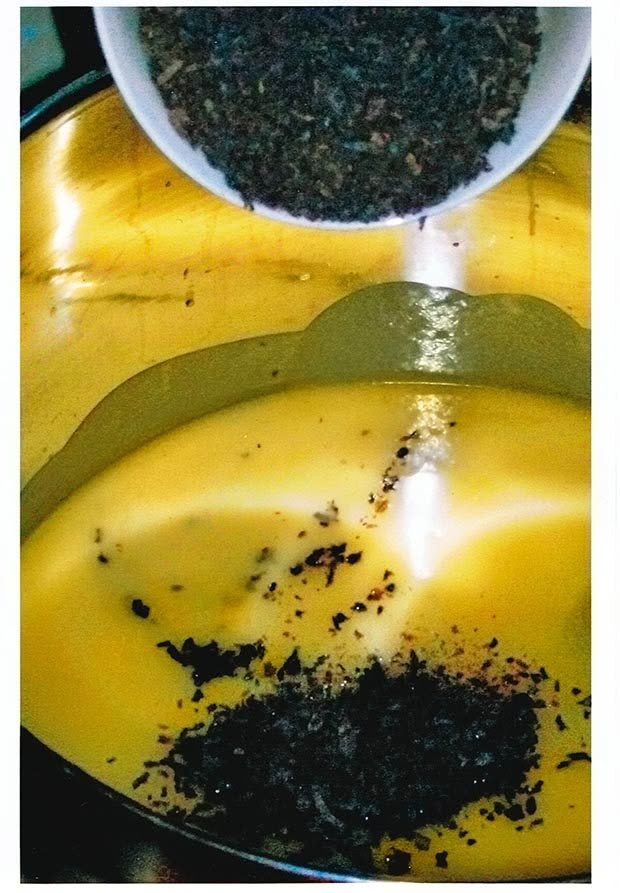

Oils are often solid in soap-making so must be melted and mixed together.

Golden Bay is not an easy place to make a living. Its isolation and small population means that people have to be innovative and creative at earning those precious dollars. The internet has helped enormously where business owners previously struggled to reach distant markets.

Kerryn liked the idea of selling an environmentally friendly product with well-sourced ingredients. Her soap is 50% olive oil which she finds hard to source in New Zealand, but she feels this will improve as more olives are grown. Soap-making doesn’t require table grade olive oil as a second pressing of lower grade oil works well.

The other ingredients are certified organic coconut oil from the Philippines and certified organic palm oil from Columbia. Kerryn stresses that this type of palm oil is from a sustainable, well-managed source, completely different from the palm oil that receives bad press when indigenous forests are felled for plantations. Buying from an organic source encourages sustainable management and helps promote organic growing.

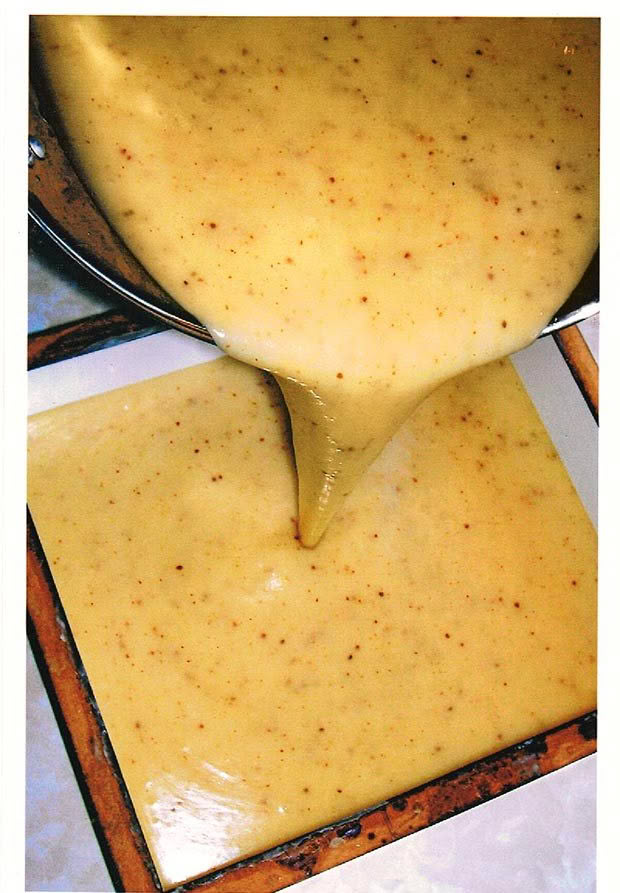

Pouring the hot soap mix into moulds.

To make the soap, Kerryn gently heats and melts the coconut and palm oil to a liquid and adds them to the already liquid olive oil. A lye solution is then used to saponify the oils.

Lye is caustic and tricky to make which is why Kerryn prefers to buy it. The last ingredients to add to the mix are the essential oils which give the soaps their appealing aromas.

The mix is poured into moulds and left for 24 hours before being taken out and cut. Kerryn’s soap cutter comes from Canada where hand-made soap is popular, and every batch she makes is cut into 220 perfectly-even pieces. The soap is then cured – a process which takes six weeks – then the soap is ready to be packaged and sold.

The finished product, cut into individual pieces.

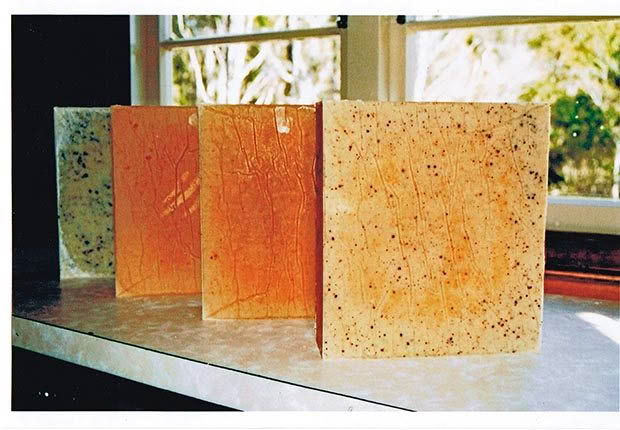

When they bought the business, it was producing four different scented soaps but Kerryn and Phill have now increased it to 10, and they believe there is potential to expand the range further. They have also been pleased with the response to a new dog soap and shampoo, and gift options of scented soaps wrapped in coloured felt.

Kerryn sells the soap on their website, and to shops in the North and South Islands. She has a market stall in Takaka and also travels to other craft markets in the summer months. She says she enjoys the interaction with her regular customers, and there is great local support and a number of repeat internet customers. Unlike selling food products, soap keeps, so there is no wastage, but fortunately there has been good demand for it.

The soap is made in slabs which are then cut to size.

The best part is the satisfaction of selling a product from a cottage industry that is appreciated by customers, and doesn’t harm the environment, says Kerryn.

“We live in such an amazing country. It’s about looking after it.”

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.