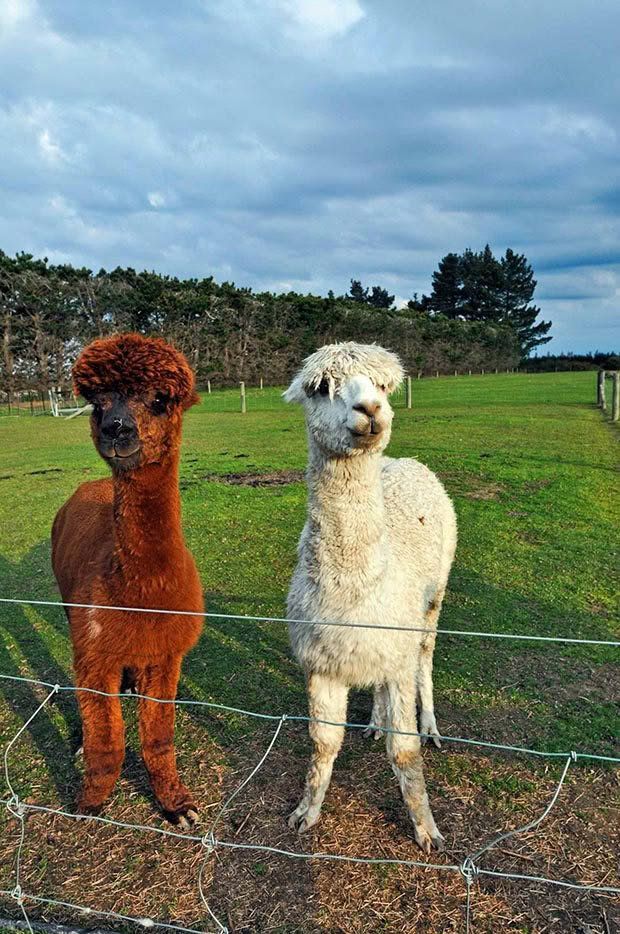

Learn the basics: alpaca farming in New Zealand

Sharpen up your alpaca knowledge with some tips from alpaca farmer, David Bridson.

Words: David Bridson

Who: David & Heather Bridson, Elysian Alpacas

Where: Katikati, 25km north of Tauranga

Land 7ha

Livestock: huacaya alpaca, beef cattle, red turkeys, hens, geese, ducks

We got into farming alpaca because my wife Heather loves alpaca fibre. To the Incas, it was known as the ‘fibre of the gods’ and when you feel it, you can tell why: it is softer than wool, hypoallergenic (it can be worn next to the skin, even by babies, without irritation), is finer than most cross-bred wool and on a par with merino for fineness, and the hollow fibre traps air, giving it excellent insulation properties. It’s why we called our farm Elysian Alpacas, after the heavenly destiny of the heroic and the virtuous in Greek mythology.

The colour range of natural alpaca fibre is extensive too. The New Zealand Alpaca Association’s colour chart has 16 different colours of alpaca fibre, from white through fawn, to brown, black and grey. Thirty percent of the alpaca in New Zealand are white and 31% light fawn or fawn. Light colours are easily dyed. While we started farming alpaca for the fibre, we have grown to admire alpaca as a farm animal in their own right. They produce heavenly fibre and pelts, but their meat is also tender and delicious, a realhealth food .

All animals have their pluses and their minuses but if I were to rank alpaca against beefcattle, sheep and goats for ease of farming (I cannot include deer because I have never farmed them), I would place beefies first, then alpaca, goats, sheep.

Alpaca are light on their feet and don’t cause soil compaction or erosion, they are easy to work with because they are intelligent animals, and they are relatively low maintenance. For example, their strong herd instinct works for the farmer. We find that if we treat them quietly and gently they will act quietly and gently. Much of the time, if we open a gate and say, “through the gate”, they will see what to do and go through the gate. What sheep or calf will do that?

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT ALPACA

There are two kinds of alpaca. Huacaya are the woolly ones that look like sheep with long necks. Suri have fibre hanging in long ‘dreadlocks’. Huacaya fibre is spun, carded, dyed and either woven, knitted into woollen garments or felted, and Heather turns our second-grade fibre into beautiful quilts. Suri fibre is generally woven and made into fine cloth for the fashion industry. About 85% of the alpaca in New Zealand are huacaya.

Alpaca can live up to 20 years. They have a gestation period of eleven and a half months so have one baby (cria) every year up to about the age of 10. After that, we will give them a break for six months and then get them pregnant so they can still continue to give birth if they are fit and strong enough up to the age of 15. This year, we had two 14-year-olds give birth.

MATING

Alpaca and other camelids are induced ovulators. Females do not have a regular oestrous cycle but ovulate after mating with a male. Mating in alpaca is very entertaining as it’s usually done sitting down –quite often, non-pregnant females sit down in readiness when a stud male (called a macho) is nearby. Males have commendable ‘staying power’ and it is not uncommon for a mating to take 30-40 minutes. While this is happening the male sings to the female (known as ‘ogling’) and she will turn her neck and look lovingly up at him.

If a female becomes pregnant and the male is reintroduced to her, she will spit at him which is how we can tell the female is pregnant.

Paddock matings are more convenient provided that we put an unrelated male with a small group of females, but we tend to mate the maidens in the yards so we can check everything is ok.

BIRTHING

Females are remarkably sensible about giving birth, known as unpacking. It mostly occurs during the daytime and on a reasonable day. Females can defer labour up to a certain point – in other words, they can switch it off. We have found that reduced rations around the time of unpacking seem to help because unborn cria and their mothers are not overweight.

SOME THINGS THAT CAN GO WRONG AND WHAT TO DO ABOUT THEM

FACIAL ECZEMA

The risk period for facial eczema (FE) is from November until April. It is caused by a fungus called Pithomyces chartarum which grows in the decaying vegetable matter in the bottom third of the pasture. The fungus produces a toxin called sporidesmin.

The name ‘facial eczema’ is misleading; alpaca rarely develop facial lesions. The most potent effect is that the toxin causes liver damage which is potentially fatal so often the first sign that it is prevalent is a dead animal out in the paddock. It is best to prevent FE as you can’t treat it. We often have high humidity in summer so we prevent facial eczema by not overstocking which means stock are eating longer pasture, away from soil level where the spores are present, and feed zinc alpaca pellets (zinc stops sporidesmin’s ability to create the toxic byproducts that damage the liver).

We feed the alpaca pellets in long, towable plastic troughs so that as many animals as possible can get around the trough. If it is raining then we try to feed out in covered feeders to keep the pellets dry.

RYEGRASS STAGGERS

This is caused by a fungus or endophyte that releases a toxin that causes head nodding, staggering and unsteady walking in affected (usually young) animals. It is best prevented by having a broad range of grass species in the pasture rather than predominantly ryegrass, and not overstocking so animals are feeding on longer (older) pasture.

If animals are affected, get them out of the pasture into an area free of it and feed them alpaca nuts or Lucerne hay.

POISONOUS PLANTS

Watch out for nearby shrubs or weeds that may be poisonous. We haven’t found this to be a big issue but you do need to check what plants are within reach.

This is a good list of plants toxic to alpaca: www.thealpacaplace.co.nz/articles/farm management/poisonous-plants/

DAVID’S 7 LAWS OF ALPACA FARMING

1. Less becomes more: you think that buying 10 alpaca is a fairly small number. Before you know it you have 20 or 30 of the animals, and surprisingly quickly!

2. Little ones become big ones: even the scrawniest of cria will in time grow up to be a big mother or father.

3. If you really want girls, you will have boys. There is a corollary to this law – if you really want boys, you will have girls.

4. Everything takes at least twice as long as you think it will: always be realistic about what you can achieve in a day.

5. Go with the flow: if they don’t want to go through a gate at the top of the paddock, take them through the gate at the bottom of the paddock.

6. Where you have live ones you will have dead ones: Rates of death and disease in alpaca are actually very low, but they do happen. Alpaca are very stoic and can disguise that they are unwell until you find them dead out in the paddock. With small numbers of animals, you feel these losses a lot more. With a larger number you can absorb the occasional losses more easily.

7. Good things take time: You have more time than you think (thank you Mainland Cheese), so don’t rush things.

WHY WE’RE EXCITED ABOUT ALPACA FARMING

We believe that we could already be at a point of inflection in an exponential growth pattern which could see as many as 600,000 alpaca in New Zealand by 2030.

For the alpaca industry in the future we need markets for fibre, live animals, pelts and meat. This has to be the focus of our efforts but already there are people with vision who are leading the way.

The New Zealand alpaca industry is in a state of transition from being predominantly a breeding industry to a farming one. I predict that in the years to come, more and more farmers will switch to alpaca as a viable farm animal which gives good returns. This is a very exciting time to be in alpaca because we are starting to see people really farming them, rather than just breeding them.

DAVID’S BIG CONFESSION: WHY BEEF CATTLE ARE EASIER THAN ALPACA

My rationale is that beef cattle, once past weaning age, are easier to care for than alpaca.

I could do a similar analysis for sheep and goats too. I put sheep last because they are so silly and there’s twice yearly shearing (depending on breed). Goats require housing or shelter, which sheep don’t, and goats have a tendency to escape poorly-fenced paddocks,

but they are good-natured animals and much more predictable than sheep. Both suffer from footrot, although sheep are prone to flystrike.

Alpaca don’t seem to be, unless they are wounded and then they are fair game, just like any animal. There isn’t a lot in it.

Personally, I like alpaca because you can build up a relationship with them due to their intelligence, but cattle have lower inputs of time.

Beef cattle pros: easy care (low ongoing costs), great with gorse, will eat grass on alpaca poo patches.

Alpaca pros: light on land, have some brains (intelligent), no NAIT responsibilities.

Beef cattle cons: Heavy on land, not high in intelligence, NAIT responsibilities, drench 2x yearly

Alpaca cons: A,D & E injections (twice-yearly), five-in-one (once a year), hooves trimmed, drench 2x yearly, shearing, leave large poo patches of grass which they won’t eat, ongoing costs of time and materials.

WHAT DO ALPACA EAT?

GRASS AND HERBAGE

Alpaca graze on pasture but also love to browse plants like tree lucerne (tagasaste) and other shrubs within reach.

ZINC ALPACA NUTS

These are fed from November to April to prevent facial eczema and ryegrass staggers.

HAY, SILAGE OR BALAGE

This is often fed out during late autumn, winter and early spring, depending on region and climate conditions.

WHAT TO DO WITH ALPACA AND WHEN TO DO IT

Annual:

• Mating

• Unpacking (giving birth)

• Shearing (we shear in November)

• Five-in-one vaccine

Twice-yearly tasks:

• Vitamin A, D, E injections

• Drenching for intestinal parasites

(in spring and autumn)

Two-monthly tasks:

• Check hooves and trim where

necessary

One-offs:

• Brass ear tags for registered animals

3 FACTS ABOUT ALPACA

• Alpaca (Vicugna pacos) are members of the camel family, albeit the South American branch.

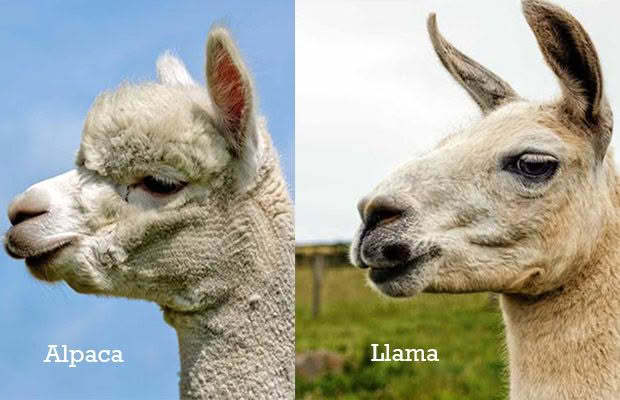

Their South American relatives are guanaco (Lama guanicoe), vicuña (Vicugna vicugna), and llamas (Lama glama) which people commonly confuse with alpacas. If you are one of those people, the basics are:

– alpaca are about half the size (70kg vs 150kg+ for a llama);

– alpaca are shorter (85-90cm at the shoulder, vs 100-115cm for a llama);

– llamas have banana-shaped ears while they’re more spear-shaped in the alpaca;

– llamas have a longer face, almost kangaroo-like, while an alpaca is more that of a teddy-bear toy.

All can interbreed. They’re so closely related to each other that if you cross any two of these species the chances are that the progeny will be fertile, unlike the offspring of horses and donkeys, the sterile mule.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

NZ Alpaca Association- www.alpaca.org.nz

International Alpaca Registry- www.alpaca.org.nz/international-alpaca-registry/

READ MORE

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.