Kurow lavender farm’s sweet smell of success

- Sam’s thumbs are now permanently stained green with a hint of purple.

- The lavender field is made up of grosso and super varieties.

- Sam gathers lavender bunches in preparation for drying.

- Betty the caravan is a recent addition and although Sam admits she cost a little too much, she couldn’t resist her charms.

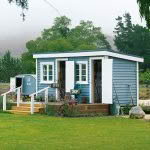

- Purchasing the cute building for the shop didn’t hurt the wallet too much – it was a steal at $100.

- Sam’s beautifully-crafted lavender soaps.

- Sam’s recently renovated kitchen doubles as a lab.

- Daisy helps her mum brew, bottle and brand the products.

- Luke’s home “office” has good indoor/outdoor flow and views that would rival the best city skyscraper.

- The hallway is one of the girls’ favourite places to play.

- Jazz the dog takes a rest in the field.

- Sam hhas two miniature horses and two highland cattle.

- Ludo is one of a duo of portly pigs.

A picture-perfect lavender farm, is just one of a bunch of businesses nourished by a Kurow dairy farm.

Words: Cheree Morrison Photos: Jane Ussher

From the boundary rider’s hut little has changed in the past 150 years. To the left, Kurow has spread, steady and strong.

The Waitaki River still flows, a lifeline for farms such as this, and the hills glow gold in the afternoon light – the boundary riders who once patrolled the valleys would recognise them as their own. From the hut, all is as it was, and as it always will be.

On closer inspection, there’s a three-legged cat, a deaf border collie with one black ear and one white one, two small blonde girls in pink gumboots, a bunch of international workers, tourists snapping pictures of lavender fields, a woman writing a book about poo and an enormous cow called Handbag.

Westmere Farm is home, business and playground to the Laugesen-Campbell household – Sam Laugesen and husband Luke Campbell, daughters Daisy (five) and Sylvie (four). Three years ago they moved from a mid-Canterbury farm, to a 1100-hectare one in Kurow (pop.312), nestled in the Waitaki Valley.

Sam uses her lavender to make soaps, balms and fudge.

It wasn’t a tough decision; Luke could see that dairy farming in Kurow provided a lot more bang for their buck (the couple are in partnership with Sam’s uncle Andrew, who runs the Canterbury farm) and the water supply was more certain than in Canterbury or the Waikato, where he began his farming career.

His 1300 jersey and friesian cows graze happily on the lush grass, filling their bellies, and udders. Unlike delicately-nostriled townies, Luke loves a good whiff of manure; it smells like happy cows and money.

They’re a well-matched pair, Luke and Sam.

Both have pure milk running through their veins; Sam’s a fifth-generation dairy farmer and while they first met in their early teens (Sam’s uncle was dating Luke’s mum at the time), love didn’t bloom until they locked eyes in the milking shed of another uncle’s farm a decade later.

The added responsibility of children, and also having staff, means they no longer have to rise before the rooster to milk, but would leap from their beds at 4am every morning given the choice – it is in all honesty, hand on heart, their favourite time of day.

Sam’s an animal person. Despite the family legacy, she fell into dairy farming after packing in a computer job in New Plymouth and shifting south to a family dairy farm to consider her next step. “I wasn’t told farming was a career option for women.

It was never mentioned at school so I had no idea how much it offers. You need brains, you need business skills, and you need to be good with people. I once dreamt of being a vet but farming has parts of that – I was able to look after and help animals every day without putting down old cats.”

The girls are now her priority, but Sam’s still a vital part of the farm, especially during the calving season when it again becomes a full-time job.

Last year she raised 850 calves, and like all years before, she cried herself to sleep when the bobbies left the gates. It’s part of the job, but never gets easier. “We care. We adore our cows, our staff adore our cows, they are the reason we are here. I love, love, love it.” Luke can still point out Sam’s pets in the hundreds-strong, near-identical herd – and not only because they come up for a cuddle during his visits to the paddock.

Their girls are never far away (cries of “Where are you, Mum?” are always answered by “Where my voice is” – the same reply her own mother gave) but as they have found their feet (or pink gumboots), Sam has found herself looking for

new ways to occupy her once farm-filled time.

One of two highland cattle.

She’s not one to sit still, or to see an idea flitter and pass her by and as a result her business card could read “full-time gardener, creator and maker of lavender products, petting-zoo wrangler, published author and proprietor of the smallest store in New Zealand”.

The lavender was planted before they purchased Westmere and was being tended by a kind local, but Sam saw potential – particularly as her driveway was often full of tourists hoping to visit the lavender fields. So she pruned, clipped, shovelled and tended until her back ached.

She purchased a ramshackle railway hut for $100 off TradeMe and sanded, painted, restored and decorated its rimu and matai walls, then she Googled and YouTubed how-to videos to learn how to create products to fill her tiny shop. Westmere Lavender opened the summer of 2014. “The shop is my girl cave,” she says.

Her soaps, balms, oils, fudge and dried bunches disappear quickly, scenting the tourists on their journey home (an average summer weekend can bring in $300 per day). Yet the sweet-smelling flower has to compete for attention with a bunch of eccentric animals.

They’re a photogenic bunch – there’s Handbag, a giant hand-raised cow who comes running when called, and Wilbur the kunekune who is currently on an expensive course of dog arthritis medication and his mate Ludo who sits for food.

The highland cattle come with a warning sign about their enormous horns – they tend to forget about their head accessories when greeting their fans. All of the petting-zoo gang know visitors equal food and go doe-eyed and sweet at the first sign of a campervan. Sam’s not one to play favourites, but Sylvie and Daisy aren’t as fair – they both love Maggie the miniature pony.

While Luke and Sam hope that perhaps one day the mini-Campbells might swap their little pink gumboots for full-sized Red Bands and join the farm, the girls have other ideas.

Daisy has been watching mum carefully and is taking notes for when she opens her own lavender farm and shop one day, while Sylvie wants to be a mummy, just like her own. High praise indeed. Seeds of future plans are being sowed, this is not a family to sit still for long. Yet they don’t travel too far from home when the opportunity arises – after all, why leave what Sam knows is the best place in the world?

Sam’s lavender products are popular with tourists.

THE SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS

Sam’s thumbs are now a permanent shade of green (with a purple tinge) thanks to endless hours in her 1800-plant lavender patch. There are 10 varieties to tend to, but the field itself is made up of grosso and super. Armed with a hedge trimmer, it takes Sam around a month to prune the plants, with regular breaks to ease her aching back.

The Campbell family are used to the sweet scent of lavender, especially on the days when Sam sets herself up in the kitchen with melting pots, mixing bowls and wine bottles filled with her locally distilled lavender oil. She’s currently working through the 2014 vintage, a strong, hearty brew thanks to the 12 wool sacks stuffed full of lavender carted over to Waimate where it was distilled. No two batches are the same; formulas are overrated.

It’s all about the smell for Sam – if it’s not potent enough, keep on pouring more oil. But this is also a family affair; Luke’s the guinea pig, he has nice lavender-soft feet hiding in those gumboots.

Daisy applies the labels with intense concentration and Sam’s learnt to accept that if some are lopsided, it makes it all the more authentic.

Once brewed and bottled, Sylvie and Daisy carefully stack the bottles and pottles in the little store.

Local teenagers are on hand during the summer to help with sales to the never-ending stream of campers, cars and cyclists.

Sam quickly learnt that it’s not easy to drop everything and run the several hundred metres down to the store whenever she spots (through the kitchen window) a car pulling in, especially with two youngsters and a hearing-impaired canine shadow.

The girls take a moment to read their mum’s book.

A BOOK ABOUT POO

“Luke the Pook came about when Skellerup released the Junior Red Bands a few years back.

“The kindy had a line of these teeny-tiny gumboots snaking out the door – farmers absolutely loved them. Like a lot of my ideas, it came to me in the shower.

I was thinking that someone needed to write a book or do something about them, and then thought, why shouldn’t it be me? I jumped out and wrote my first draft in an hour.

“The story was simple – the farm is covered in poo and kids tend to jump in it.

“I shelved it for a couple of years when the girls were young, but when they were a little older I dusted it off and sent it to a script assessor, who gave me great feedback. I considered submitting to a publisher but was wary, as I had heard that some stories are never read or are overlooked and I wanted to avoid rejection.

“I knew I had something good, so found an illustrator and had it published locally in Oamaru.

“I tested the waters on a local Facebook page and had 300 orders overnight, then the first 1000 printed sold out in a week, then a second 1000 sold out as well and now we are on the third print run.

“In total, the book has sold about 4700 copies. I’m working on the second book now.”

Westmere dairy farm

THE LOW-DOWN ON DAIRY

* At 1100ha, the Laugesen-Campbells’ farm is on the larger side and runs from the top of a valley down to the Waitaki River. The irrigated hills have lush green grass that the girls love to roll down – as long as the cows haven’t left too many presents.

* There are about seven staff members (“our farm family”) on the farm and they milk twice a day, for about four hours each time. The farm used to support

one family, now it could support seven to eight families.

* Irrigation pivots and a set grid system were installed during the past two years. Before irrigation, the land was rough, rugged and grass was sparse.

* About 200 litres of water is used per second, with 50ha covered by the river and the rest from the Laugesen-Campbells’ creek.

* The 600 wagyu beef in utero are the latest innovation with export plans. What would Luke do if he wasn’t dairy farming? He has absolutely no idea. It’s never crossed his mind.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.