Island Bay’s marine conservation warriors are on a mission

A haven for marine species and a place for schoolchildren to discover sea life runs on the generous time of volunteers and the tireless efforts of a pair of devoted enthusiasts.

Words: Kate Coughlan

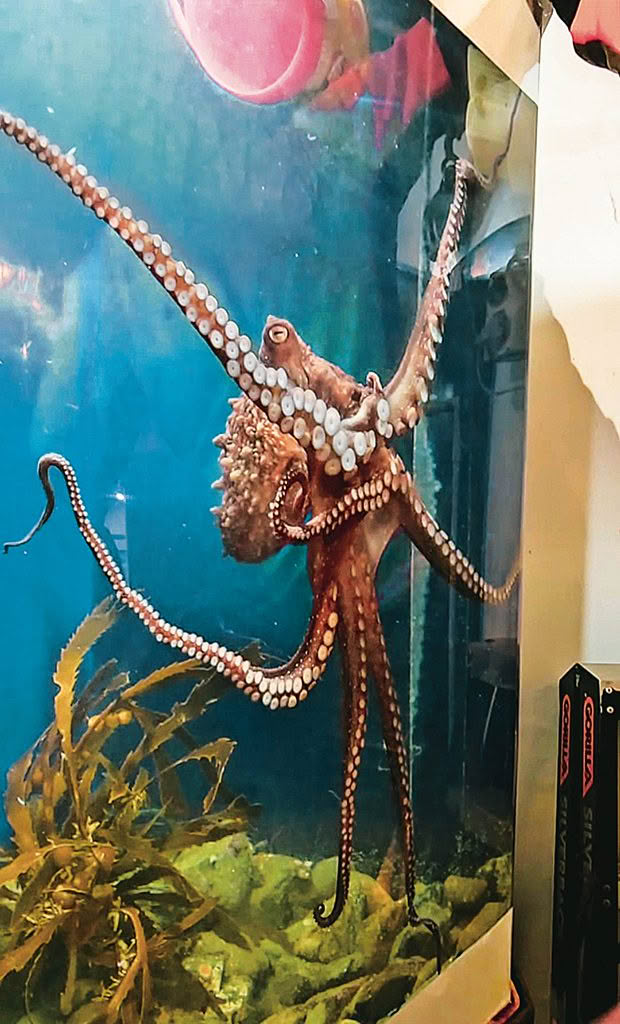

In a shabby old yellow building on the edge of Wellington’s south coast, an octopus named Damian is playing with a brightly coloured toy. He pushes the toy up and down his glass-sided tank, showing off the dexterity of his eight legs, his eyes high on stalks above his head, swivelling as he watches his watchers. They are mesmerised, their eyes glued as tightly to Damian’s display as his legs are to the toy.

Playtime comes after lunch; a paddle crab lowered into the top of his big tank in a bright red kid’s bucket, red being his favourite colour. Damian swarms — all flashing legs — eagerly seizing the bucket and tipping it over, knowing it contains food. He injects the crab with poison from his beak to soften it before swallowing it with a mouth located halfway down his underside.

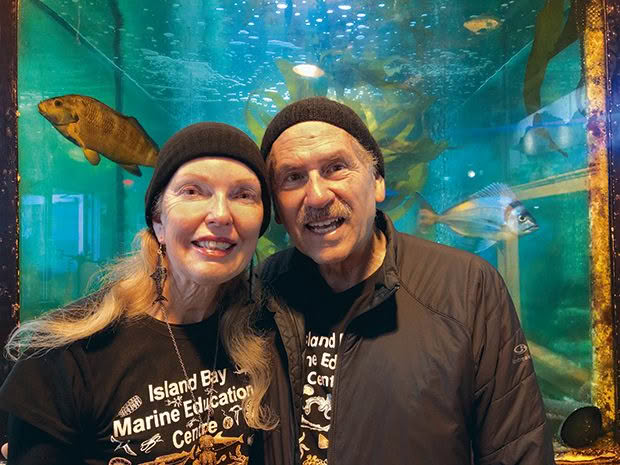

The octopus has been at the Island Bay Marine Education Centre for a few months, brought in for nursing after being found injured by a fisherman. Dr Victor Anderlini and his partner Judy Hutt run the Island Bay Marine Education Centre, homing numerous sea creatures in what used to be the Island Bay fishermen’s bait shed.

“Octopus have a short life,” says Victor, a Californian-born and educated marine biologist who came to the southern hemisphere in 1973 to look for pesticides in Antarctic penguin eggshells. He found the pesticides, sadly, but stayed, delighted by being able to drink fresh water from any lake or river in New Zealand. Not everything since has delighted him as much.

Twenty-eight years ago, he and Judy established their marine centre and began collecting old fish tanks and aquatic species to live in them. Today the duo provides a haven for marine animals in numbers too hard to count, with an open invitation to the region’s school children to come and discover, literally firsthand, what is in the sea surrounding Wellington.

Large petting pools allow little kids to understand how gently they must lift the brittle starfish so their long limbs are not damaged, how they must replace the tiny periwinkles right-side-up after handling them and how soft starfish are to the touch. Many animals in the tanks are permanent residents but not the two octopi.

“We keep an octopus for about four months so their limbs can regrow before we free them in the marine reserve. After all, octopi only live for about five short years, so we must let them get on with mating.”

The five elegant seahorses, batting their delicately fringed eyelashes at the goggled-eyed visitors, also have their reproductive life explained by Victor. Male seahorses carry eggs to hatching. They have a pouch, while the females have a ridge from which they deposit eggs into the male’s pouch.

Judy says her explanation of a seahorse mating ritual — during which the male puffs up his pouch and sways in a seductive dance before the females — always draws guffaws from landlubber blokes, saying they do much the same, but they bloat their pouches with beer before a mating dance.

For 28 years, Judy and Victor have battled to keep the centre open to instil a sense of wonder about the marine environment. They love working with the children who, Judy says, are like little sponges soaking up massive amounts of information.

“They’re the ones who will be responsible for our seas and our marine life in the future, so we try hard to set them on the right track — as early as possible.”

The centre is open to the public every Sunday, and Dr Victor is often so eager to welcome guests and introduce them to the wonders of the underwater world that he forgets to push the clicker to count them. On the day after the end of one Covid-19 lockdown, Wellingtonians poured through — 400 in one day.

Meanwhile, Judy’s daily battle is seeking funding. The aquarium may run on the smell of a salty rag and the kindnesses of volunteers, but without money, it cannot survive.

HOW TO HELP?

The Island Bay Marine Education Centre could not exist without volunteers and donations, especially since the Ministry of Education stopped subsidising schoolchildren’s class visits. The kids still come, of course.

But the centre has had to increase admission fees to $8 for adults and $3 for children (up to 16 years). Donations are sought, as are volunteers (over 14 years). Contact: judyhutt@octopus.org.nz

Open to the public every Sunday from 10am to 3pm. Schools by appointment.

GOAL

“To inspire wise stewardship of New Zealand’s marine ecosystems and resources for present and future generations by providing an opportunity to see and learn through live displays of local marine life and exciting, hands-on, interactive formal and informal educational experiences.” octopus.org.nz

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.