Into the woods: An architect puts her lessons to practice with a hut overlooking the Whanganui River

Catherine and boyfriend Cass Goodwin enjoy views of the Whanganui River from the west-facing deck. The loading-dock door covers a glass slider when the hut is not in use.

An architecture graduate put the theories learned in the classroom into practice and built her own tiny hut in the woods.

Words: Polly Greeks Photos: David Whorwood

Originally published in the Jan/Feb 2011 issue of NZ Life & Leisure.

It’s been called a chapel for its quiet serenity and likened to a Scandinavian sauna for its clean wooden lines but Catherine McEntee views the hut she’s built overlooking the Whanganui River as a teacher.

While the School of Hard Knocks doesn’t usually equate to the hammering of nails into wood, that’s what Catherine’s extramural education has involved as she’s spent her spare hours planning and building her structure.

Recently graduated from the University of Auckland’s School of Architecture, the 28-year-old began work on her place three years ago when lectures on house design proved too inspiring to simply sit back and listen.

“The course is primarily theoretical and I’m a practical person. I was itching to put the theories into practice.”

The hut is an idyllic retreat which Catherine plans to share with friends.

Teaming up with a now-ex-boyfriend, Catherine drew the blueprint for the 18-square-metre building and picked a pine-covered spur on her parents’ land near Taumarunui for the construction. A steep learning curve followed as she picked up the building vernacular and came to know her struts from her studs.

“I’ve learnt a lot but I’ve been very fortunate with the local community. Initially everyone thought I was bonkers but now they all love it. People have been so supportive. I’m going to put on a big party this summer for everyone who has helped.”

Catherine’s family bought the Taumarunui property in 2005 and, along with friends, use it to indulge passions for fly-fishing and snow sports. The surrounding land looks like chocolate-box country, with Mounts Ruapehu, Tongariro, Ngauruhoe and Taranaki all visible from the main house.

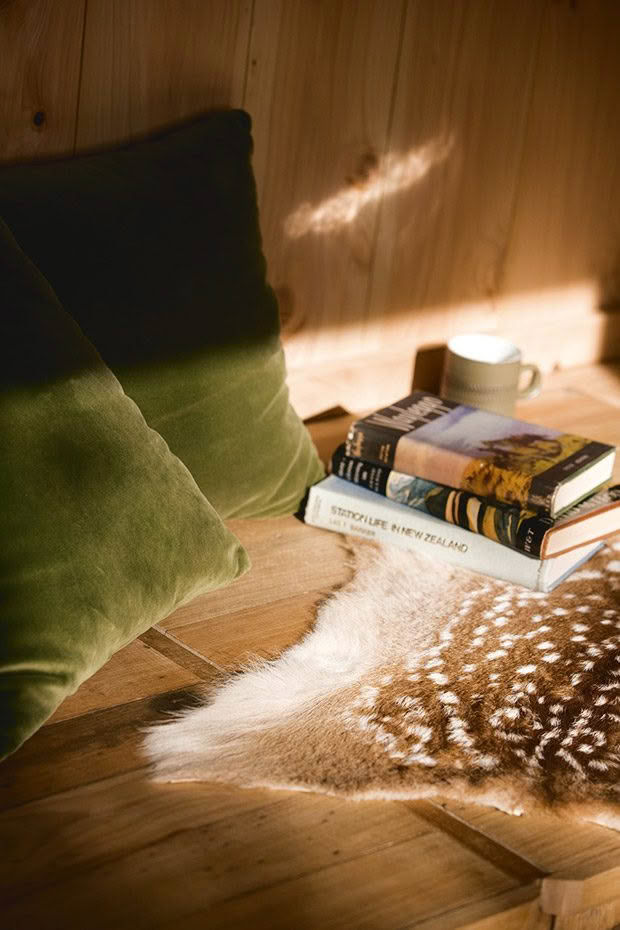

Her nearest neighbours are curious deer which frequently gather at the fence line to see what she’s up to.

“It’s a magical spot,” Catherine says of the almost-five hectares. “We have converted some of it into an orchard. Mum and Dad love growing things and Dad wants to be able to eat his breakfast straight off the trees.”

While the house has electricity, Catherine’s building site and the resultant hut do not, which is something she’s come to value.

“I enjoy not having power. There’s an element of peace to it. It’s allowed me to observe the rhythm of things in nature. Plus, next door’s deer might not visit if the TV was on.”

Nor does the hut have drive-on access. Instead, visitors must descend the steep ridge from the house or stroll the more genteel way around the hill.

Although it has just been finished, the hut looks as if it has sat in its clearing forever. Its unobtrusiveness is partly thanks to the cladding of old corrugated iron nailed to the macrocarpa walls.

Sourced locally, the materials cost Catherine $20 and a box of beer. The matai front door was found at the back of the upper-house woodpile and required 15 hours of elbow grease and three metres of 40-gauge sandpaper to rid it of its seven paint layers.

The old woolshed floorboards used inside needed stripping of lanolin and nails, while 50 hours went into the chequer-board kitchen bench-top, made from painstakingly laminating together jackstud offcuts left over from the hut’s subfloor construction.

Recycling as much as she could, Catherine found an ingenious use for old horse-shoes as a coat rack.

Despite woolsheds being a good source of materials, Catherine says high-country mustering huts have been of more inspiration to her.

“Architecturally they’re not particularly evolved but their integrity, the way they’ve been put together, is worth looking at.”

To complete a final university paper she recently spent time in the South Island’s high country researching its mustering huts. She returned filled with stories from retired shepherds, some now in their 80s, many of whom had helped construct the huts in order to escape accommodation in old bell tents.

Cupboards surround the hut’s kitchen sink and bench along the southern wall. Catherine found the light fittings in a garage sale and turned them upside down to hold tea-light candles.

However much Catherine’s hut resembles something from the backblocks externally, indoors it is obvious an architect’s hand has been involved. Filled with light, the small, clean space flows easily from the kitchen to the living area where a wood-burning Studio oven provides heating.

“I use it for baking fish and bread. It was the last thing to come in and it was like the heart going in.”

A tawa seat running the length of the lounge is the width of a single bed and provides storage beneath, while overhead the mezzanine floor has been built of slats, “like a shearing-shed floor”, to allow heat and light to filter through.

The cantilevered ladder leading up to the mezzanine was co-designed with Catherine’s current boyfriend to prevent it from being a visual and spatial interruption, Catherine says, while the upstairs bed has been countersunk into the floor to allow more head room. A trapdoor in the south-west corner of the kitchen floor reveals a laundry tub suspended between the floor joists and cunningly used as a fridge.

“It’s the coldest spot. Ice took 36 hours to melt last winter.”

- Bread and fish are baked using the wood oven which warms the whole hut. The cantilevered ladder leads to the slat-floored sleeping area.

While the dictum for new houses is seemingly “bigger is better”, Catherine says she loves small spaces.

“There’s an energy about them. I live in a very small apartment in Auckland (36 square metres) so I’ve come to be very aware of the efficiency required in small spaces.

What I’ve found with this project is that things I would never have dreamed of on paper have become the most beautiful details of the building. When you have to problem-solve on site with the materials in your hands, the more practical and often more elegant solutions have become obvious.”

The cantilevered ladder leads to the slat-floored sleeping area.

Now that the hut is complete, Catherine is uncertain what her next undertaking will be. Currently converting an attic into office space for a client, the fledgling architect is compiling her CV and hunting for other jobs.

She is also a soprano opera singer with six years of voice training under her denim dungaree straps and feels it’s time she overcame her shyness of singing in public.

Pondering aloud on her future, her glance falls on the old woolshed at the bottom of her parents’ land and a thoughtful gleam enters her eye. “That might be the next project. I’d like to convert it into a brewery.”

As the people around Catherine have learned, if she sets her mind to it, not only will they be drinking her beer before long but it will have been produced in a work of art.

CABIN IN THE WOODS

Total cost: $20,000.

Overall dimensions: 6m x 3m with a monopitch roof. Rear wall (east) stud height 3m, front wall (west) height 4m.

Construction style/type: Timber frame construction with recycled corrugated iron cladding. The cladding is branded Newport, Great Britain, and is believed to date back to before 1930 when New Zealand began rolling its own iron sheets. It’s often been called pre-rusticated iron with an emphasis on the rust. However, these older irons are a lot thicker than today’s stuff and should have a good few years’ wear left in them.

Power and water: The Studio oven allows cooking and stove-top water heating. The converted 1970s light fittings safely house tea-light candles, the moon provides night-time ambience and rainwater is collected from the roof (new long-run corrugated iron to avoid lead poisoning).

A rainwater tank stores the hut’s water supply. Slightly built Catherine found certain building tasks required manpower from Cass and neighbours to shift heavy timber into place but says the main hurdle in building the hut was the issue of continuity, with university demands keeping her Auckland-bound for lengthy periods.

Eco aspects: Built by hand using no treated timbers or toxic/synthetic materials. The structural timber is untreated macrocarpa as is the interior lining. The concrete piles, beams, flooring, doors, ladder components and joinery were salvaged from demolition, and most have been restored by hand. The insulation is EcoWool®. The Studio is a highly efficient wood-burner: up to 14kW/h. Orientated to take advantage of the afternoon/evening sun. Catches own water (as above). Site planting in an effort to regenerate native bush.

Originally published in the Jan/Feb 2011 issue of NZ Life & Leisure.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.