Inside Paloma Gardens: Meet the couple who spent 45 years planting their tropical garden in Fordell

She has the brains; he has the vision. Together, this couple has developed an extraordinary and surprising garden.

Words: Lucy Corry Photos: Tracey Grant

When Nicki Higgie wants to tease her husband, Clive, she reminds him of the advice her mother-in-law gave her many years ago. “She told me that if there were a plant in the garden that Clive liked and I didn’t, I could just wander out and pour boiling water over it,” Nicki says. “She obviously knew that Clive was going to be a plantsman.”

- Knowing that steps deterred visitors from exploring further, Clive used leftover paint to transform the dull grey concrete of the stairway leading to a Steuart Welch sculpture.

It says much about the Higgies’ long partnership in love, life and gardening that Nicki’s never stormed out of the house, steaming kettle in hand. Because, as they will both attest, Clive Higgie is not a man moved by fleeting garden fashions.

He cares little for trends and delights in being contrary, even if that sometimes means choosing plants his wife doesn’t particularly like. Nicki, who Clive describes as “the brains” of the operation, is no shrinking violet either. Together, this remarkable couple presides over Paloma Gardens at Fordell, 20 kilometres from Whanganui.

The Desert House is home to the Higgies’ accumulated collection of cacti and succulents, such as the towering Aloidendron dichotomum or quiver tree, indigenous to South Africa.

Paloma, their very own Eden, is less a garden and more a kind of living gallery devoted to exotic and curious flora. The Higgies have created 10 distinct zones, each with a carefully curated selection of plants and trees.

It’s a structured wilderness, mixing plant life with sculpture and other built design elements to remarkable effect – and one of New Zealand’s Gardens of National Significance. It’s a place in which to be awed and inspired, especially considering that neither of the Higgies knew much about gardening when they started.

- Notocactus magnifica.

- The distinctive Macrozamia macdonnellii, a cycad endemic to Australia’s Northern Territory.

- Morawetzia sericata.

- Alluaudia procera.

“A lot of people say, ‘Oh, you’re so lucky, you’ve inherited somebody else’s work,’” Nicki says. “We say, ‘There’s no luck involved, and we started from scratch.’” “It’s taken 45 years to get to this stage,” Clive adds. “My problem is, I keep having ideas, and it’s hard to tone them down.”

The first clue that Paloma is different from any other garden is writ large across an expanse of black fence at the entrance. Here, aphorisms and quotes in multiple languages are daubed in white paint. “That’s my favourite,” Clive grins: ‘Happy wife, happy life.’”

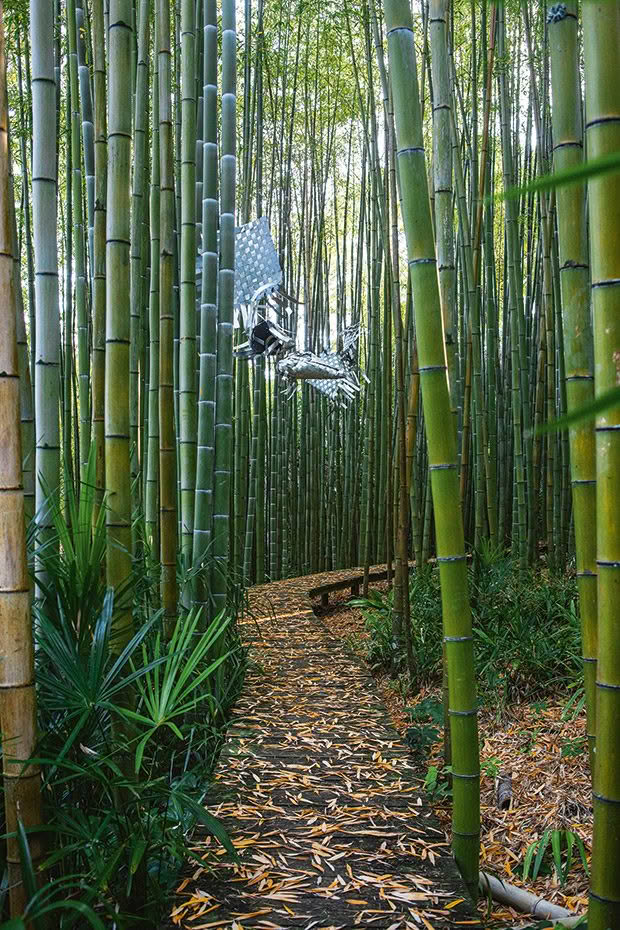

Paloma Gardens’ bamboo forest was grown from seeds the Higgies planted in 1990. The floating woven aluminium sculptures are the work of an artist unknown to the Higgies.

From here, the garden leads in multiple directions. There’s formal (the neatly manicured Wedding Lawn), lush (the Palm Garden), dry (the cacti and succulent-filled Desert House) and wry (the mock-macabre Garden of Death).

Somehow, it all flows together. Nicki says this is Clive’s doing. “He has a good sense of what a plant needs, where it will look good, and how to make the whole thing work. He does a lot of reading and research, but more than that he just gets out there and does it,” she says. “I can also go forward 25 years and imagine how things will look,” Clive says. “On the whole, I try to respect the future.”

That ethos has stood Clive in good stead ever since he met Nicki, who was a friend of his sister’s at Victoria University, in the 1970s. Clive wasn’t much of a gardener back then. He had grown up near where Paloma Gardens now stands, the fourth generation in his family to run the now-600-hectare sheep, beef and forestry property. Clive’s life revolved around the farm and riding his beloved motorbikes, but he was dazzled by his sister’s glamorous, sophisticated friend.

Clive’s first great love — “before I met my darling wife”, he says wisely — was a motorbike. This handsome 1971 Norton Commando Fastback LR is the same model he adored as a younger man.

“I was a country bumpkin. Back then, pizza was topped with Wattie’s spaghetti, and I had never tasted an olive. Nicki had lived all over the world because her father was a diplomat, and I thought she was quite classy.”

Love bloomed quickly and the pair married in 1974. City-slicker Nicki settled happily into life on the farm, and the couple started planting a tree every year or so. “Just ornamental or shelter trees, nothing special,” Nicki says. “In 1980, when I was pregnant with our eldest son, we bought seeds for the washingtonia palms – and they all grew. If they hadn’t germinated, we might not have continued. But it was very successful.”

When looking at the towering washingtonia palms (or fan palms), now nearly 40 years old, that seems like an understatement. The trees look as if they belong on a film set, with their vast, smooth trunks and lofty crowns. Washingtonias also form the grand avenues of The Wedding Lawn, and they’re the grand pillars of Paloma’s Palm Garden, which has 130 palm species, along with bamboos, alocasias, ferns, orchids, and cycads.

About the same time, the Higgies bought a few more subtropical plants from a Northland nursery, tucking them into the back of the ute on their way back from a holiday. They came home, planted them, and they thrived in the temperate, almost frost-free climate. Little by little, Paloma Gardens sprang into life. Nicki and Clive would sit by the fire on long, winter evenings and thumb through plant catalogues, making plans. “Initially, and even now, we were planting for the plant, not the flower,” Clive says. “Most people do the opposite.”

- Fuchsia boliviana.

- Puya venusta.

- Lilium ‘Black Out’.

- Brugmansia ‘Deep Gold’.

- Aloe polyphylla.

Clive is an innate collector, Nicki says. “Once he got started, he just kept going.” Their plant collections (“Clive’s the plantsman, I’m the supporter”) have enlarged along with their knowledge and hands-on experience. “In the early days I would buy one of everything, then the emphasis changed to making it look good,” Clive says. “I remember when I first learned about succulents and wondered what the difference was between a yucca and an aloe. Now I can pick it at 200 yards.”

The Higgies’ collection tends to favour the exotic rather than local, but they successfully blend the two. In the Palm Garden, fragile orchids bloom out of almost-sculptural ponga logs, showing how well plants from different places can co-exist. “Clive doesn’t discriminate against any plant on political or geographic grounds,” Nicki says. “A good plant is a good plant.”

“People get so hung up on where a plant comes from, but there’s no point,” Clive says. “The Norfolk Island flora is closer to ours than that of Australia but, politically, the island is Australian.”

In any case, the birds don’t seem to be worried, Nicki says. “People tell us that we have more flowers in the garden in the middle of winter than any other garden they know, largely because we have a lot of southern African plants that flower then. We have tūīs, waxeyes and bellbirds all year round. They don’t discriminate either.”

The couple opened the gardens to the public about 30 years ago, and have hosted countless visitors since, often for weddings and other celebrations. Some even stay longer, using the Higgies’ B&B properties or camping on the lawn.

As the gardens have grown, so has the Higgies’ reputation among gardeners – and their circle of like-minded friends. Whanganui artist Michael Capenerhurst gifted the couple his vast collection of cacti and succulents, which now occupy the Desert House. Other contacts have given them cuttings or seedlings, which have flourished as Paloma Gardens has created its own micro-climate.

It’s certainly a very different eco-system to when Clive’s father ran the farm, and young Clive spent weeks every year cutting down “a hell of a lot” of macrocarpas and shelter trees that his grandfather had planted decades before. “My father went through his whole life, and he never planted a single tree,” Clive says. “He knew a lot about trees, and he loved the patches of bush that were left. But he was a green desert man and trees were in the way.”

Clive and Nicki have hosted many weddings and celebrations on the aptly-named Wedding Lawn, which is defined by an avenue of washingtonia palms.

Luckily, the Higgies’ three children have all inherited their parents’ love of plants. Oldest son Marc is an arborist, middle daughter Simone has a PhD in evolutionary biology, and youngest son Guy is now in charge of the farm. “Guy’s not particularly sympathetic to trees unless they’re planted in strategic places for the good of his stock,” Clive says. “But, luckily, the farm’s big enough for both of us to have our respective areas.”

One of the couple’s most ambitious projects has been the creation of two arboreta at Paloma. The Norton and Matchless arboreta, which Clive started planting in the 1970s and 1990s respectively, have rare trees from around the globe. The most special (asking Clive and Nicki to name their favourite tree is akin to asking a child to pick a favourite sweet) are gathered near Longway, the earth labyrinth that Clive dug by hand.

Here, trees are planted to commemorate the family’s diverse ethnicities. The ashes of Nicki’s mother are also buried here, near a Cross of Lorraine-inspired sculpture made by Clive. Now “98 per cent” retired from the farm, Clive still has plenty to keep him occupied. The most recent addition to Paloma Gardens, the aforementioned GoD, or Garden of Death, remains a work in progress. “We were visiting our daughter in Brisbane and in the library, I found a book about poisonous, stimulant, hallucinogenic and irritant plants. I thought, ‘Right, we’re going to make a garden out of these plants and call it the Garden of Death.’” Nicki, he says, groaned.

- Tillandsia spp/hyp.

- Tillandsia spp/hyb.

- Masdevallia coccinea.

- Golden lily.

The GoD draws plenty of visitors, though the couple are amused that they often have to explain why they’ve included socially acceptable “poisons” like hops, tequila agave and sugarcane. Clive, a lifelong teetotaller, also plans to add a grapevine.

In the meantime, there’s a dramatic Dracunculus vulgaris (“I put it in here because it stinks of death”), lethal oleander and other plants of varying toxicity, including hogweed and rhubarb.

“A year ago, we had a busload of women here, and I pointed out this Kalanchoe grandiflora and said, ‘Give your husbands a leaf of this, and they’ll drop dead,’” Clive says. “Then I realized what I’d said and felt terrible, but they all loved it.” The GoD fits with the slightly fairy-tale feel of Paloma Gardens, which is defined by elements of surprise and delight rather than straight lines and neatly clipped topiary. Clive’s intuitive design stops it from feeling stage-managed or formal.

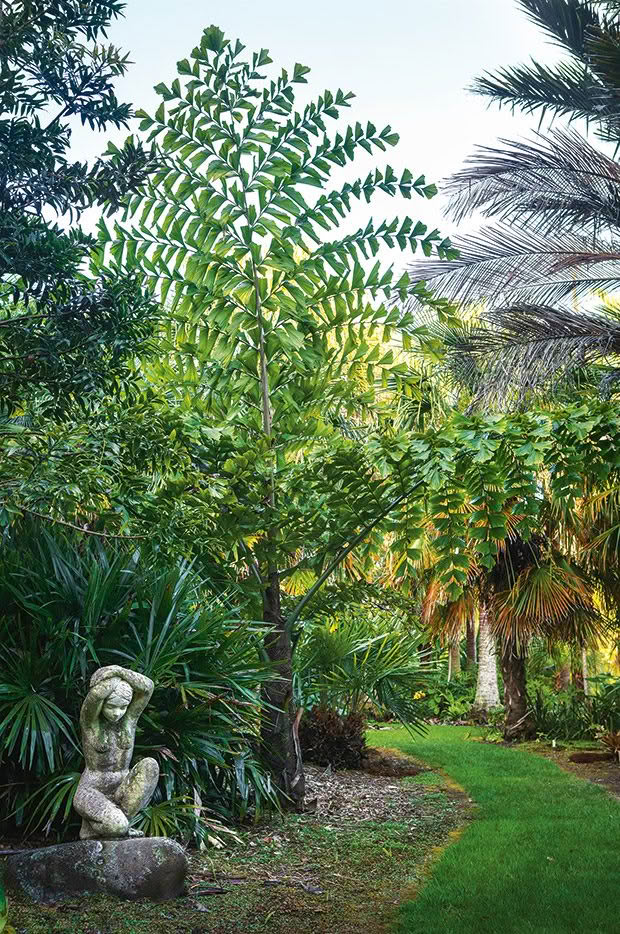

A figure carved by a Wairarapa artist crouches beneath a Caryota gigas.

“What we love about it is that almost every plant has a story,” Nicki says.

And, like all stories, there’s always room for one more, even if a happy ending isn’t always guaranteed. Clive’s eyes light up as he describes one of his latest finds, a golden variegated tradescantia with which Nicki is yet to fall in love. Will it succumb to the “sudden wilt disease” caused by a targeted splash of boiling water?

“In theory, I have the power of veto, but that doesn’t always work,” she says. “We’ll see.”

PRIVATE OASIS

The Higgies receive hundreds of local and international visitors to their garden every year, giving them a chance to observe human nature at its best and worst. Nicki chuckles as she recalls a recent visitor who had to be steered away from peering into the couple’s home. “She was quite surprised,” Nicki says. “She said, ‘What, do you really live in that shed?’ Parts of the roof indeed need painting, but we’d rather spend time in the garden.”

The private garden around the house remains Clive’s favourite part of the property. “I still love our first garden, even though it’s changed a lot. It’s my definition of outdoor living because it has hard landscaping and lovely plants. I’d come home from the farm, totally knackered after a day of working flaming hard, have a shower and sit out here. This part of the garden is very relaxing.” It’s also dog-proof, providing a safe, visitor-free spot for the Higgies’ beloved dachshunds, Claude and Pablo.

ART IN THE GARDEN

It’s difficult to tell whether the Higgies’ extensive grouping of ceramics and steel sculptures has grown to fit the garden, or whether the garden has extended to meet the collection. “Some have been given to us; some we inherited from my parents. And we’ve had fun buying some,” Nicki says.

- A corten steel cube by Steuart Welch.

- A collection of pieces by 1980s New Zealand potters.

- Drawing the Line, a sculpture by Whanganui artist Ivan Vostinar.

- A collection of ceramic pieces by Doreen Blumhardt.

- An imported bronze torso.

- A ceramic by Ivan Vostinar.

- Not Simone by Steuart Welch.

The Pottery Walk contains a who’s who of New Zealand ceramic art from the 1970s to today, including works from locals such as Ross Mitchell-Anyon and the couple’s son-in-law, Ivan Vostinar, alongside an ever-growing number of classically shaped Burrelli pots made by Peter Burrell in Marlborough. Paloma Gardens is also home to several significant steel works by Marton sculptor Steuart Welch.

Clive started off making the plinths, then moved on to casting his own larger pieces. “It’s the old thing: if you want something done, you have to do it yourself. I’m not original, but I like making things. “I’m quite mechanically minded; it just comes in a kind of natural way.”

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.