How you can transform an old, cold country house

Transforming an old, cold home into one with a much greener footprint is a slow but satisfying, cost-effective DIY project.

Words & images: Nelson Lebo

Who: Nelson & Dani Lebo

Where: Kaitiaki Farm, 10km east of Whanganui

What: permaculture, regenerative agriculture

Land: 5.1ha (13 acres)

Web: ecothriftylife.com

If there’s one thing I know well, it’s living in a cold, country home. We’re lucky enough to have owned three properties like that.

Over the past seven years, I‘ve also visited around 2000 homes in my role as the eco design advisor for Palmerston North City Council. My job is to help occupants find cost-effective solutions to improve their health and comfort, such as how best to insulate, heat, and ventilate their home, so it’s warmer, drier, and healthier to live in.

I spend the bulk of my waking hours – and sometimes my dream time too – thinking about redesigning existing spaces, indoors and out, to function better for both people and the planet.

WHAT IS AN ECO DESIGN ADVISOR?

There are seven councils in NZ that provide homeowners with a free eco design assessment by an independent eco design advisor (EDA). An EDA doesn’t sell you anything and offers completely independent information.

The goal is to help people update an existing home to be warmer and drier, or design a new, highly efficient one.

Some people I’ve helped call me the House Doctor. I go through it room-by-room or check plans for a new home, looking for design issues, such as:

■ where heat is being lost or gained, eg insulation, windows, drafts;

■ how to improve heating;

■ reducing moisture sources;

■ increasing ventilation;

■ improving the hot water system.

I enjoy the science and art of ecological design, and that’s helped us significantly as we’ve slowly renovated our 85-year-old house near Whanganui.

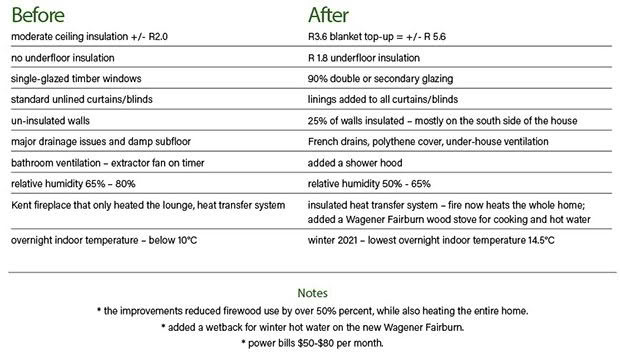

The renovation and retrofit of our house is an excellent case study in synergistic effects of minimising internal moisture, retaining the warmth, and distributing heat throughout the home.

The improvements from retrofitting a home are often incremental. You only notice the cumulative effects one day by pausing to observe, “Wow, that’s so much better than before.”

I’ve taken what I call an eco-thrifty approach to improving our house. It’s a philosophy I always take into retrofit and renovation, striving for the most benefits for the lowest overall cost, with minimal material sent to landfill.

Problem 1: Moisture

The home was damp when we bought it, primarily due to poor drainage and inadequate sub-floor ventilation. Water from the yard and driveway flowed underneath the house, causing several piles to rot prematurely.

There was also very little sub-floor ventilation due to bark mulch from garden beds blocking many of the vents around the sides of the house.

THE SOLUTION

I built a French drain to divert the water. This is a trench with perforated drain coil lying in it. It’s covered with stones, allowing water to seep through into the drain and run away.

Due to the ground slope, trees, and concrete surrounding the house, it was easiest to direct the stormwater underneath the house rather than trying to go around it.

Once complete, I laid a heavy-duty polythene moisture barrier under the entire house. Even then, it took a year and a half for the home to dry out fully. However, the drop in humidity and the rise in the overnight temperature show it was time well spent.

When we had heavy rain, stormwater would run through the carport. Cutting the concrete allows the water to seep through, and it’s then directed into a drain.

The bathroom already had a good extractor fan on a timer.

I installed a shower hood which means there’s no condensation in the bathroom unless the children have a particularly long play in the bath on a cold day.

Problem 2: The thermal envelope

The trapdoor into the roof space was too small for Nelson and the insulation, so he removed a sheet of roofing iron.

The house had the bare minimum of ceiling insulation.

Doubling or even tripling the layer of insulation in the ceiling is one of the best and easiest things you can do to improve a dwelling’s thermal envelope. The Building Code minimum specifies the very lowest level of insulation, so if you’re building a new house, you need to go well above it.

THE SOLUTION

Insulation

I removed a couple of sheets of roofing iron to make it easy to install the large rolls of blanket insulation.

I over-ordered and used the excess to cover the ducting of the existing heat transfer system. This unplanned, simple retrofit turned out to be one of the best of the entire project.

For the walls, I chose the ones that could be most easily insulated without penetrating the internal or external linings (which in most cases would require building consent).

Nelson nailed battens onto the existing wall, then filled the spaces between them with insulation. Once covered with wood, it’s also a stylish feature wall.

On the four walls I’ve done so far, I’ve attached evenly spaced 50-70mm framing timber to the inside face of the wall, then insulated the gaps with polyester batts. It includes this feature wall in the master bedroom (right), a plywood climbing wall in the kid’s room, a wall in the office, and two closets along a south wall.

Glazing

At present nearly all the French doors (we have four sets) and windows have either double glazing or perspex secondary glazing. The choice of which one to use goes right to the heart of my eco-thrifty approach, based on observations I’ve made over the last decade.

If you have timber-framed windows and apply secondary glazing on the inside, moisture may still get between the panes on the windward side of a home during heavy rain. It can take days, sometimes weeks, to dry out unless the panel is removed (screws or magnetic).

That’s why I only use secondary glazing on timber-framed windows where wind-driven rain won’t reach the putty, such as in recessed entryways, on covered decks or carports. Otherwise, I consider the best choice is to retrofit double-glazing with low-e glass.

This is an easy way to convert a ‘cold’ door into a ‘warm’ one. 1. Measure and cut insulation to fit. 2. Cover with thin ply or similar. 3. Repeat on the other side. 4. Paint to suit.

The window from our dining nook looks out to the carport. Since the outside isn’t exposed to rain or direct sunlight that could degrade the panel, I ‘triple glazed’ it with layers of Perspex applied internally and externally.

I also converted a traditional four-panel glass door into an insulated one on a budget of next to nothing by reusing second-hand materials and small offcuts. We now also have lined Roman blinds for the kitchen and dining areas and detachable curtain linings for the existing unlined curtains.

DIY BUDGET OR RENTING?

You can buy inexpensive kits which stick insulation film to wooden window frames (not aluminium).

The transparent film creates a layer of still air in front of the glass that acts as insulation, just like double glazing. You only need scissors and a hairdryer to install it. However, the view out of a window won’t be as crystal-clear as plain glass, and the film needs to be replaced every 1-3 years.

More expensive DIY kits use Perspex sheets and screws but are clear 3mm plastic that’s stronger than glass.

Double glazing vs secondary glazing

Double glazing: factory-made ‘insulating glass unit’ (IGU)

Secondary glazing: an extra layer of clear material – usually perspex, plastic film, glass, or even bubble wrap – added to an existing single pane of glass with a gap in between.

Problem 3: Heating and Heat Transfer

In theory, heat transfer systems in homes with wood burners are a good idea. The huge Achilles heel is they have a net cooling effect on the home.

This is mainly due to minimal insulation around the long runs of ductwork that supply warm air to distant bedrooms.

Ducting is typically installed on top of ceiling insulation. Warm air from the fireplace exits the thermal envelope for the journey to the bedrooms, losing warmth the whole way, then re-enters the thermal envelope considerably cooler. While the air in the lounge ceiling may be 30°C+, it can fall to as low as 10-20°C as you get further away.

THE SOLUTION

Insulation

Fortunately, retrofitting insulation around ducting is quick, easy, and inexpensive. Where the ducting in our ceiling lay flat, I covered it with R 3.6 blanket insulation. Where it connected to a suspended fan, I double wrapped each side with polyester under-floor insulation and taped it up like a whiskey barrel.

The difference in performance for us was immediate and substantial. The old Kent fireplace used to heat just the lounge. By improving our home’s thermal envelope using insulation, and super-insulating the heat transfer system, it now easily heats the entire house. For a typical home, the savings in firewood over one or two winters would probably pay for the upgrade, a 50-100% return on investment.

A modern wood stove

We rarely need to light the Kent these days. That’s because we installed a Wagener Fairburn wood stove in the kitchen for cooking, hot water, and space heating.

Here, we made another small choice that’s had a big effect, opting for a heat saver-type flue rather than a standard flue.

To keep the outside of a standard flue cool, there’s an air gap between the flue and the flue casing. Air is drawn in from the room, fills the gap, and is expelled. This hugely inefficient system means large volumes of newly warmed air are sucked outside.

For not much more money, newer eco or heat saver flues draw cool air from the ceiling cavity or outside, so all the warm air stays inside.

1 easy way to warm your home

One of the first and easiest actions I took when we moved in was to cut down a tree and trim back branches on another on the north side of the house. Both blocked the house from receiving crucial midday sun in winter.

A year later, that same wood – now cut and dried – warmed the house, fueling the wood burner.

THE RESULTS

The entire family is happy with the way the house feels and performs. My nine-year old daughter loves lighting the fire, and her younger brothers enjoy playing in a warm bedroom. I’m getting ready to order more glazing panels for the last couple of windows. That means, after 7+ years, the job might be… almost done.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.