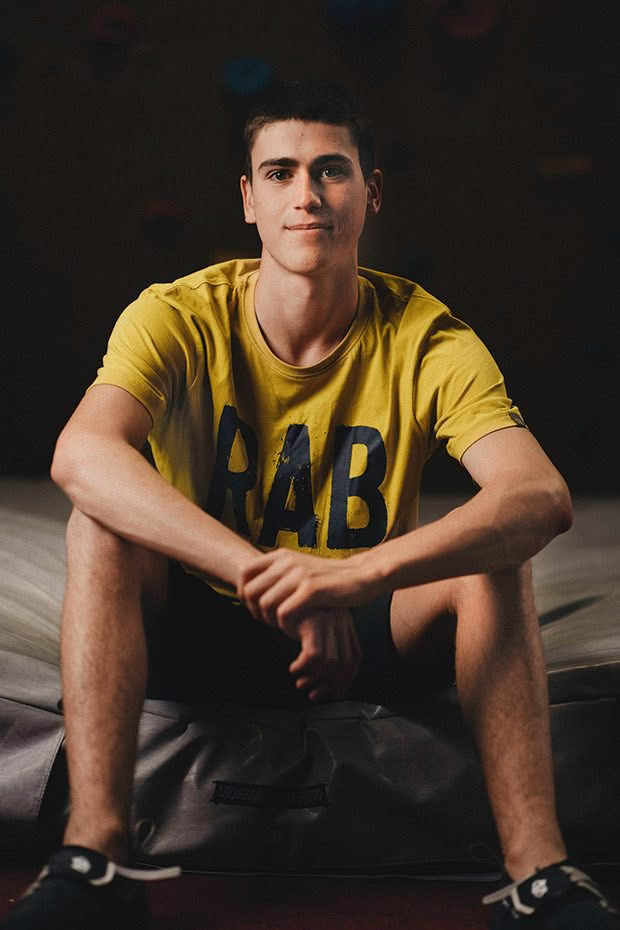

How Tom Waldin turned his daredevil hobby into a career as a professional climber

Sport climbing has been around since the 1800s, but thrill-seeking Gen Z-ers have made it so popular it has earned a place at the Olympics.

Words: Heather Kidd

Superhero characters such as Batman, Superman and Spiderman have thrilled generations of comic book readers and movie buffs, wowing fans with their superpowers. Thanks to the wizardry of special effects and almost-superhuman stunts, they can leap, jump, and fly themselves into and out of danger.

Away from books and cinema screens, real people are engaging in daredevil sports such as bouldering, a form of sport climbing that requires them to scale outdoor rock formations with as much agility as a superhero.

No special costume is needed, just a pair of good climbing shoes, a bag of chalk, and a well-trained mind and body. Tom Waldin (21) is one of New Zealand’s top boulder climbers and a speed-wall star. He won the men’s section of the 2021 Aotearoa Championships and has represented New Zealand at the IFSC Climbing World Youth Championships.

Tom took up climbing in 2013 during his first year at secondary school, encouraged to have a go at the indoor form of the sport by some of his Rotorua schoolmates who were keen climbers. “I was pretty instantly hooked. Climbing was natural for me. I’d enjoyed climbing trees as a child, and I loved the combination of mental and physical agility.”

Traversing indoor climbing walls is one thing; speed climbing is quite another. In competition, speed climbers must scale a 15-metre “plastic” wall in the shortest time possible, negotiating a set route using what are known as holds. The men’s world record, by Veddriq Leonardo of Indonesia, stands at 5.208 seconds. Tom’s best time is 9.138 seconds (set in 2019).

While Tom has proved himself to be a competitive speed climber, his preferred disciplines are lead-climbing (with ropes) and bouldering. “Speed is quite different to the others because there’s no problem-solving aspect. I only climbed indoors at high school because there was no suitable outdoor terrain for lead and bouldering.

But moving to Christchurch to attend university meant I could broaden what I did with the sport. I was drawn to the outdoor bouldering at Castle Hill [100 kilometres from Christchurch] where, obviously, all the climbing surfaces are not necessarily five metres high like in competitions. Some are quite high, which I enjoy because you must be confident and in control and aware of how you move. You must understand the subtlety of climbing to scale heights without being worried about falling.”

And falling is very much a part of climbing. “Bouldering is mostly about falling, and you can fall a hundred times before you successfully climb one rock,” Tom says, which explains why he adopts a safety-first approach and doesn’t climb alone.

While lead climbing requires climbers to be attached to ropes belayed by others, bouldering is entirely free form — mental stamina and physical strength, flexibility, dexterity and agility aiding a climber’s ascent. And should they fall, it’s (hopefully) onto crash pads placed at the base of the boulder.

Despite the risks, Tom has suffered only one bad injury. In 2017 he snapped a thumb in half while training. Although the injury was painful, what hurt most was being unable to compete in the IFSC Climbing World Youth Championships held in Austria.

Sport climbing is all about problems — and problems appeal to Tom. They are why he’s chosen to study civil engineering — he recently graduated after four years’ study — and problems are one of the main reasons he loves to climb. A problem is the term used to describe the specific route athletes take via a sequence of moves to climb either an indoor bouldering wall or an outdoor boulder.

“I’ve always loved problem-solving, and climbing, particularly lead and bouldering, is not just about the physical. It also requires a lot of mental attributes. Competitions are exciting; you must solve problems under time pressure. You’re climbing boulders you’ve never seen before, and there’s very little time to look at them and understand how to climb them.”

The pressure of time is a significant factor in competition. In bouldering, climbers have four minutes to complete a course successfully. They can make as many attempts as the time allows; speed climbing is all about being the fastest to complete a route successfully, and lead climbers have six minutes to have one go at scaling a wall.

Outdoors and away from competition, a climb is more personal. It’s not about beating the clock; it’s about not letting the boulder win. Tom might decide to keep his feet on the ground while examining the rockface and working out a route he hopes will get him to the top.

Or he might get going straight away, using his knowledge and experience to help him navigate his way past problems. If the boulder is higher than the norm, repelling down it first is an option, searching for holds and positions and working out whether a climb is feasible.

In mid-2021, Tom successfully scaled Middle Trifecta, one of the most famous boulders in New Zealand. The sense of accomplishment was immense; it had taken him two years of trying. A new challenge will be heading overseas when travel once again becomes possible and pitting himself against the best sport climbers in the world, something he got a taste of in 2019.

“I attended World Cup events in China and the World Championships in Japan. I loved being on the world stage, although it was somewhat overwhelming, and I’m hopeful I can now be competitive and in with a chance of making the semis or the finals.”

He’s also eyeing up the opportunity to test himself at some of the most well-known sites in the world, including Rocklands in South Africa and Ceuse in France, because it’s these rugged natural environments that call to him. They are where he’s like a real-life Spiderman: hanging by his fingertips, using his almost super-human strength and agility to scale seemingly unscalable rock fortresses. Solving problems.

FROM SMALL BEGINNINGS

In the 1800s, bouldering was regarded as a non-serious form of rock climbing used by climbers in training. But over time, it gained its own following. In the mid-1950s, the support of American mathematician and former gymnast John Gill, renowned as the father of modern-day bouldering, helped it become a bona fide sport.

Gill’s use of gymnastic chalk to aid climbs quickly became popular worldwide, and he is also credited with creating problems harder than the norm. Influenced by his gymnastic background and the grace of motion and form, he was a proponent of dynamic movement. He also regarded bouldering as moving meditation.

Another influential figure was Frenchman Pierre Allain. During the 1930s, he designed soft rubber-soled shoes, known as PAs, specifically for rock climbing, and they became the prototype for modern shoes.

Specialist footwear is the only essential item worn by climbers. Social media has had a significant impact on sport climbing, and its popularity has increased dramatically since the early 2000s.

OLYMPIC DEBUT

Sport climbing became an Olympic sport at last year’s Games in Tokyo, one of several action sports making their debut, included as organizers seek to broaden the appeal of the centuries-old tournament. The competition took place over four days and featured men’s and women’s events.

The IOC granted sport climbing a single medal only, so instead of the sport’s three disciplines — speed, lead and boulder — run as separate events, they were combined. A scoring system was devised that included points from each field multiplied to create a total score to determine the medal winners.

The competitors had to endure hot and humid conditions, far from ideal for sport climbing. In the men’s event, the gold medal winner was 18-year-old Alberto Ginés López, who became Spain’s youngest-ever male Olympic gold medal winner.

Nathanial Coleman (USA) won silver and Jakob Schubert (Austria) bronze. Janja Garbret (Slovenia) won the women’s gold medal, with Japanese climbers Miho Nonaka and Akiyo Noguchi winning silver and bronze, respectively.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.