How do you practice regenerative agriculture strategies on a block?

Culture farmer Nelson Lebo shares the practical ways he uses it on his 5.1ha block near Whanganui.

Words & photos: Nelson Lebo Additional photos: Brad Hanson

Who: Nelson & Dani Lebo

Where: Kaitiaki Farm, 10km east of Whanganui

What: permaculture, regenerative agriculture

Land: 5.1ha (13 acres)

Web: ecothriftylife.com

One of my favourite pastimes on our block is simply to take it all in. I’m pretty busy with work, children, and farm life, but I always make sure to regularly pause to admire how the land is thriving month by month, year by year. The best times to do this are dawn or dusk, with either coffee or beer in hand.

If you practice regenerative agriculture, I’m sure you’ll feel the same.

It doesn’t happen often, but when I do get the opportunity to slow down in this way, the rewards are worth it. There’s the sense of accomplishment and the motivation to keep going. I thank nature for it all, as it’s doing the heavy lifting.

On most land managed under ‘conventional’ farming methods, nature is broken. There’s no ecosystem function and little non-prescribed biological activity. That’s why it needs increasing amounts of chemical inputs and diesel fuel.

I believe less in managing land than in managing ecologies. The point is to set nature up for success and then let her succeed. If you provide the conditions for life to thrive… life thrives!

It’s like making a small snowball at the top of a hill and giving it a nudge. Most of the work is done by forces other than ourselves. The synergies that come naturally to ecosystems kick in and result in multiple positive feedback loops.

It starts with the soil and builds from there.

Our very healthy stock aren’t drenched, and receive a varied diet of nutritious feed options.

Increasing resistance & nutrition

Healthy soils lead to healthy plants, which are less vulnerable to pests and diseases. That wisdom came from a farmer mentor of mine years ago. I’ve followed his ounce-of-prevention-is-worth-a-pound-of-cure approach to growing food for two decades.

Although our achievements are anecdotal, they’re consistent enough to instill confidence in our approaches.

For example:

• many commercial and home-grown garlic crops suffer terribly from rust – our crops have remained relatively unscathed;

• we have a low incidence of diseases in our fruit trees, despite not spraying;

• our very healthy livestock (goats, pigs) aren’t drenched;

• our goat management system appears to benefit soil health and animal health.

Water management

A swale full of water after a sudden summer rainstorm.

Building soils is our number one priority (as outlined in part one of this story). Right behind it is improving the hydrology of our block, especially after we experienced severe flooding in 2015.

Our sprawling and diverse landscape is especially challenging, requiring multiple approaches to moderate the wet-dry extremes we experience here.

The healthier soil structure has:

• increased water percolation and groundwater recharge high on the property;

• enhanced water retention from winter to summer;

• decreased surface water runoff during storms, reducing stream flow when it matters most.

We also use swales, drains, and small retention ponds. Thanks to a portable submersible pump and long hoses, we have the option of directing this saved water to different areas as needed.

Ecosystem health

This starts from the ground up, and our efforts in soil improvement have paid dividends here as well. We treat each food-growing area like an ecosystem with biologically diverse plant-animal pairings. These managed ecologies appear to get healthier year by year as more complex biological interactions establish themselves.

Planting the steep hillsides with trees more closely resembles the former forest ecosystem before European settlement. By shifting towards a browse-based system for our goats, not pasture-only, the land can better manifest its true identity – it naturally wants to be a forest, so we’re helping it do that. Forcing it to be a grassland is like putting a square peg in a round hole.

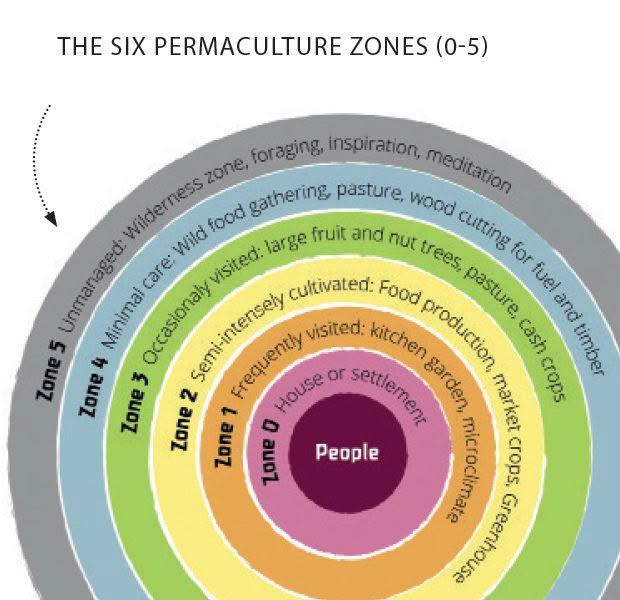

We’ve also given nature a nudge by ‘retiring’ approximately 20% of our land – including a riparian corridor and wetland areas – and planted 2000 natives and counting. In permaculture zones, it’s all Zone 5 (the wilderness areas).

Carbon sequestration

This has never been an overt goal but was a natural result of our land management practices.

The main ways we sequester carbon on our block are in the soil and trees.

While it may be obvious how trees store carbon, it may not be so clear how soils do it.

Dr. Elaine Ingham is one of the world’s best soil scientists. For over 40 years, she has advanced the concept of the soil food web, which has helped enable the restoration of ecological functions of soils around the world. Her website – soilfoodweb.com – has an excellent video on how plants help to sequester carbon in the soil.

Low-input methods

Managing water is an important strategy. Here, our intern Costa digs a drain, with help from a mother duck, ducklings, and a goose.

Having been a redneck dirt farmer for yonks, this one is near and dear to my heart. I love simple, elegant, low-cost solutions, whether it’s land management or home renovation.

In the context of regenerative agriculture, ‘low-input’ primarily refers to the use of agrichemicals and machinery. We use little of each and only when necessary.

In our moderately active plant nursery, we use a high-quality potting mix with slow-release fertiliser that we buy in bulk from a local garden centre. Some of our trees stay in pots (re-used, of course) for quite a while so it’s worth ensuring they get enough nutrients until it’s time to plant them out.

Other than this, our only fertiliser sources are homemade compost and heaps of animal poo. We use both ours and some sheep manure bought from my mate Gavo who mines it from underneath shearing sheds.

In terms of herbicides, pesticides and fungicides, our usage is similarly meager and includes:

• Triumph Gel to control the spread of gorse;

• derris dust against white butterfly;

• copper to prevent curly leaf on peaches.

The biggest piece of machinery we own is a chainsaw. It’s far gentler on the land and the wallet not using heavy 4-wheel drive vehicles like tractors. When we do need one, it’s easy enough to borrow, barter or hire it.

All this means low overheads, which helps ease financial pressure.

The systems approach

This last point could have been the first: a holistic or systems approach is the only approach to regenerative agriculture. The interconnections between the elements on a farm are as important as the elements themselves.

We’re constantly striving to maximise beneficial relationships while turning liabilities into assets in everything we do. Our aim is to work with nature – not against it – to create the conditions in which biology and hydrology do most of the work for us.

In a twist on the popular ad, it’s no spray and walk away.

Other off-farm inputs

• bulk maize and barley from a local farm;

• hay from a workmate;

• sawdust from a local pallet factory;

• lime and clay breaker from local retailers;

• food scraps from friends and neighbours.

Nelson’s 7 steps toward regenerative agriculture

• improve soil health and fertility

• increase the resilience and nutritive quality of crops and livestock

• improve water infiltration and retention

• increase biodiversity and the health of the ecosystem

• sequester carbon from the atmosphere

• employ low-input methods / reduce dependence on agrichemicals

• embrace a systems approach

Where not to build a swale

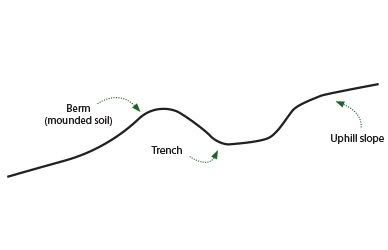

A swale is a berm (ditch + mound) perpendicular to a slope. It looks like a drain but is perfectly level, so water only exits when it soaks through into the soil or evaporates.

However, it’s critical to understand that building swales near the top of slip-prone slopes is inappropriate and dangerous. We have keyline drains that follow the slope’s natural contour in these areas, directing water away from the gullies and out onto the ridges. In this way we can spread and slow overland flow during heavy rains while providing extra water to the drier ridges.

Read more about keyline drainage: ‘Yeomans Keyline Systems Explained’

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.