Hotter than Hades in Chihuahua, Mexico

- Tourism has dropped sharply in Chihuahua and empty cantinas in Nuevo Casa Grandes have become a regular feature.

- A vacant hotel in Nuevo Casa Grandes.

- The El Indio mountains were sacred to Apaches and later a hideout for revolutionaries and bandits.

- The 19th-Century Hacienda San Diego near Mata Ortiz, one of cattle baron Luís Terrazas’ 23 homes. BELOW: A Tarahumara corn farmer at the San Ignacio Mission near Creel, where for an admission price, travellers can visit cave dwellings and inspect the handicrafts and daily routines of a people clinging fast to their old ways yet living perilously close to the modern poverty line.

- The partially excavated UNESCO World Heritage site of Paquime, a pre-Columbian city of 2000-plus adobe apartments. Said to have been developed around 700 AD, Paquime was a major trading hub until the 15th century.

- More than 40 per cent of Mata Ortiz residents are said to be involved in making ceramics, and sometimes whole families rise to the task, like husband and wife ceramicists Luz Elva and Vidal Corona Gutierrez.

- Ceramicist Ancilla Corona and husband Oscar Luiz Ramirez make pots in their dining room. Ancilla does most of the decorating, seen adding detail with a single-horse-hair brush; following the ancient sotol-making traditions of the Rarahumara people, the Jacquez family at Don Cuco aim to produce only the best. Here, the collar de perlas and taste-tests are achieved using steer horn cups.

Head into Breaking Bad territory, where land is dry, throats are parched and dogs are very very small.

Words and photos: Jason Burgess

On the hills above Juarez is a sign in white-painted stones. “The Bible is the truth. Read it.” Truth is, right now on this northern tip of the Chihuahua desert it’s hotter than Hades and the hollow promises of billboards cluttering US Highway 10 out of El Paso suggest nothing but purgatory. Debt relief, dream chasing and on-call paralegals with sparkling dental work all vow to soothe life’s ills.

Cotton fields and arid cattle ranches soon lead us west. To our left is the hideous border wall or, as our Mexican driver Alfredo calls it, el muro de la verjuesa – the fence of shame. “We can’t believe they are building that when we already pulled down the Berlin Wall,” he says. We’re travelling fast because Alfredo has to pick up some Tarahumara athletes whose home is deep in the Copper Canyon and bring them north for a marathon in Colorado. The Tarahumara are famous for their long-distance running and Alfredo’s boss is trying to raise their profile and earn them some much-needed money on the international circuit

A Chihuahuan hi-vis version of some traditional Gaucho footwear.

At the Columbus/Palomas border portal there is no vehicle queue, only a line-up of gruff, monosyllabic, paramilitary US border guards. Across the line, a young Mexican immigration officer multitasks in a Portacom, stamping paper visas in triplet while babysitting a co-worker’s toddler. Finally he hands us our passports with a hearty bienvenidos. We emerge from the Portacom and the world seems changed. Buildings in fluorescent colours burst from dusty streets, the sidewalks are alive with hawkers, walkers and food vendors. This is Breaking Bad territory. The US State Department issued a travel advisory warning Americans against driving here five years ago. The concerned citizenry dutifully obliged and the southbound traffic dried up quicker than a spilled shot of tequila on these raw sienna plains. Now is the perfect time to visit.

A margarita washes down my shrimp fajitas at the Pancho Villa restaurant in the “famous” Pink Store, a colossal, must-see arts and craft shop. A statue in an adjacent courtyard depicts the revolutionary, Pancho Villa, shaking hands with US general John J Pershing. It was from here in 1915 that Villa launched a raid on the fort at Columbus after the US double-crossed him. Pershing responded by mounting a year-long, multi-million-dollar manhunt for Villa and his accomplices. It was unsuccessful.

The word chihuahua is believed to have originated with the Nahuatl people. It means dry, sandy place. Yet after recent rains the high plains are strangely green. It is the largest Mexican state and home to one of the world’s smallest dogs, although Alfredo claims he has never seen one.

We head south through open country, where pickups are piloted by drivers in white Stetsons and the roads are lined with makeshift ramadas. Hand-painted signs promise Coca-Cola and mennonite cheese. The influence of the US is undeniable, yet the region’s rich indigenous history still informs the present.

The Guatemalan macaw was keenly traded among the Pueblos cultures of northern Mexico. Macaw feathers were so highly valued that they were used as a form of currency.

Our next drink is at Rancho La Guadalupana, where for five generations the Jacquez family has been producing sotol – a little-known local liquor – under the name, Don Cuco. Celso Jacquez is the head sotolero. He says it was sotol not tequila that was the tipple of choice for Villa’s revolutionaries.

“It is considered the Americas’ oldest liquor. Cave drawings and fire-pit evidence suggest that the production of sotol for ceremonial and medicinal practises predates Christ.” Even the state anthem Viva Chihuahua celebrates it: “Land that tastes like love. Land that has the aroma of sotol.”

When Chicago gangsters moved their operations south of the border during the prohibition era, they judged sotol too labour-intensive and slow to produce. As the city of Juarez became their giant get-rich-quick still, they had sotol outlawed and besmirched its reputation as “rotgut befitting only Indians”. Made from the heart or piñas of the sotol plant, the Indians call it the noble plant. It has been used to cure everything from a cold to toothache and muscle tension. In Celso’s office a rattlesnake lies suspended in a jar of sotol.

“Sipping this,” he says, “is believed to cure cancer.” The original don, Celso’s grandfather, Refugio Perez, learned the art of wild harvesting, fire-pit cooking and fermentation from the Rarahumara people. The same organic techniques are employed today, right down to the use of steer-horns as cups (to check for aroma) and a fine necklace of pearl bubbles (collar de perlas), an indicator of quality.

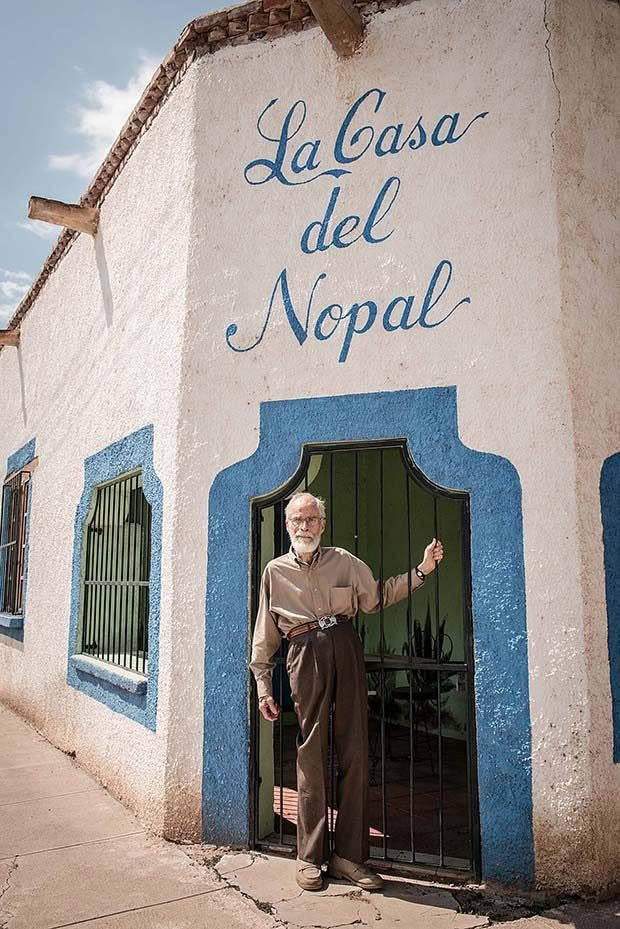

The Sierra Madre Mountains loom closer as we approach Casa Grandes. Our host at the centuries-old hacienda, La Casa del Nopal, is American Spencer MacCallum. He has been living in Chihuahua for 35 years and acts as something of a one-man tourism booster, not just for the area’s cultural heritage but also for the ceramic scene in nearby Mata Ortiz. He has restored several heritage houses in the old town. “History,” he says, “is what brings travellers here.”

A Tarahumara family reluctantly striking a pose in Creel. The timorous Tarahumara live deep in the Copper Canyon and are famed for their extraordinary feats of ultra-distance, cross-country running.

Casa Grandes (grand house) is the name the conquistadors gave to the nearby Paquime ruins, a UNESCO World Heritage site, and once-important mercantile and trading centre of the Mogollon people. Construction is thought to have begun in the eighth century. At the height of its prosperity Paquime boasted 2000 apartment-like adobe homes and a surrounding population that swelled to 10,000. Only a small portion of the maze of buildings has been excavated, characterized by their small T-shaped door portals, animal pens and sophisticated irrigation and waste-water systems. The September sun is blistering as we retreat to the adjacent air-conditioned museum.

The displays highlight the artistic proclivity of a society of craftspeople, who particularly favoured copper jewellery and exquisite pottery. The latter was used alongside seashells and macaw feathers as currency. The creative influence of Paquime is still felt today in Mata Ortiz.

Ragged peaks form a profile of a face known as the guardian, El Indio.

The peaks loom over the once-sacred Apache site of Mata Ortiz. Ironically the town takes its name from the man who was charged with wiping out the indigenes, Juan Mata Otriz. Growing up on the back of timber and cattle, the place went bust in the 1950s once the trees were stripped. The railway was rerouted and the cattle ranchers upped sticks. Lately it has been dubbed el milagro – the miracle – for its unlikely economic revival as a centre for ceramics. The reversal of fortune is generally credited to one man, Juan Quezada. His rise to fame is something of a real-life fairy tale. As a teenager, he was intimate with the mountains and became intrigued with the shards of ancient pottery he found underfoot on his sorties there for firewood. One day he stumbled into a hidden burial cave, a treasure trove, replete with unbroken ancient pots. So inspired was he by the quality, he took to teaching himself pottery, initially copying the designs, using only clay and colours found among the mountains.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

A decade later and luck struck Juan for a second time when anthropologist Spencer MacCallum picked up two of his pieces from a swap shop north of the border. Enthralled by the quality of the designs, Spencer packed the car and headed south looking for the artist.

When he finally tracked down Juan, he bought up his stock and paid him a stipend to carry on making his pots. It was the start of a relationship that continues to this day and was the catalyst for Spencer’s move into the area. But the story doesn’t end there. Seeing that he could earn a crust making ceramics, Juan Quezada then encouraged others to give it a go. In makeshift studios, bedrooms, kitchens and lounges, men, women – and, sometimes, whole families – can be found hand-shaping clay without the use of potting wheels in the manner of the ancients.

American anthropologist Spencer MacCallum has lived in old Casa Grandes for more than 30 years. It was his discovery of Juan Quezada that led to the Mata Ortiz pottery movement.

Their preferred fuel for low-temperature firing is still grass-fed cow manure or split wood, and kilns often consist of little more than backyard pits covered with metal washing tubs or corrugated iron. We drop into Juan Quezada’s gallery but he is not in. His pieces are grand, almost avant-garde. Even so, watching other backroom artisans employ hacksaw blades and home-made single-hair brushes to turn out glass-like glazes and finely painted designs is magical.

We are barely in town for an hour and the word has gone out – a couple of gringos are visiting. We are flagged down by a family of ceramicists flogging their work from a 4WD truck. Northern buyers have been scarce here lately. As Spencer says, “The only people that the war on drugs is hurting are those who are trying to make a living.”

It is a long drive from Casa Grandes to Creel at the beginning of the Copper Canyon. For the next week we will drop and climb by 4WD and rail through the landscape of the Tarahumara, a topography five times larger than the Grand Canyon, where some of the most retiring people on the planet fiercely hold fast to their own ways.