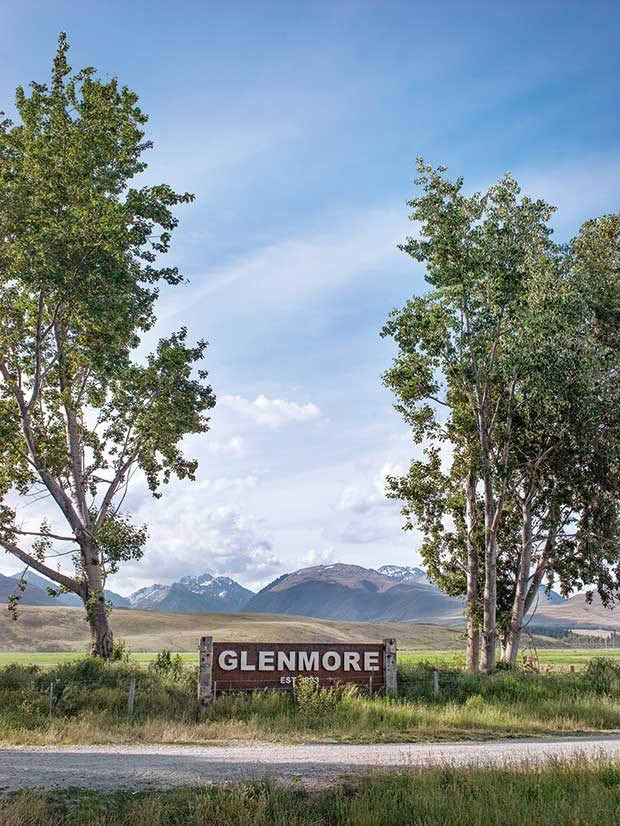

Hard work and scenic views: High country sheep farmers Will and Ems Murray are earning the good life at Glenmore Station

Will and Ems Murray are the fifth generation of the family to farm Glenmore, a high-country station bordering Aoraki/Mt Cook National Park. They aim to not be the last.

Words: Matt Philp Photos: Rachael McKenna

A while ago, a visitor from Chicago holidaying at Glenmore Station’s rustic shearers’ quarters left a note for leaseholders Emily and Will Murray.

“I have to say thank you for the incredibly hard work you do to love and care for this land,” he wrote. “From the sweat and toil to the ecological, financial and political management, it’s an astounding task.”

There’s a catch in Emily’s voice when she reads the note aloud. Farming the Mackenzie high country has always been a physical challenge, but these days the political and social climate can seem almost as harsh. Recognition is as rare and as welcome as the perfect amount of spring rain.

“We’re the guardians of Glenmore — that’s how Will and I feel,” says Emily, who is also known as Ems.

“It’s too big for anyone to claim to own it, but we have the privilege of looking after it while we’re here. To get that acknowledgement was lovely.”

Whoop the huntaway lays down the law to some ewes. The shearing quarters beyond the yards began life in a different part of the property as Will’s parents’ first homestead after they were married. It’s now a popular holiday rental.

Glenmore Station occupies 19,000-odd hectares, rising from the western shore of Lake Tekapo to the border of the Aoraki/Mt Cook National Park. An award-winning merino property (with deer and beef), it has its feet in the water and its head in the snowy peaks.

An Australian wool classer once described Glenmore as having “charisma”, not least because of the family legacy: generations of Murrays have farmed it for 104 years.

Will and Ems took over from Will’s parents Jim and Anne in 2002. Daunting? Yes. But Will, raised on the station with two sisters, had imagined farming Glenmore since he was “about one” and Ems, who was brought up on a lowland South Canterbury property, had long since lost her heart to the place while walking its tussocked hills on autumn musters.

Ems got her first working dogs when she moved to Glenmore, and now shares a team of five with Will.

Although it has to be said there were moments after she got together with Will, and persuaded Jim to employ her and her team of dogs, when she wondered if she was up for the high country. It was beautiful, yes, breath-taking even, but also relentlessly demanding.

“I remember one night bursting into tears and saying, ‘I don’t know if I can do this.’ I loved farming but I’d only seen the outsider’s romantic view of the high country, and this was a whole other world. It can be overwhelming.”

For the past 16 years, they’ve been flat-out, making their mark on the farm while raising three children, Angus, 12, Greta, 10, and seven-year-old Ben.

“When you wake up, you can’t lie in bed,” she says. “You think ‘I have to do this, and this, and this’, and away you go. There’s a huge sense of purpose, in a really positive way.”

Looking south towards Lake Alexandrina, which borders Glenmore on its northern shore. Spring-fed Alexandrina is a renowned trout-fishing lake with three fishing camps, the earliest dating back to 1918. During winter, the northern end can freeze solid.

But there’s also time for fun. During winter, when for a couple of months not a blade of grass shows above the snow, Will can spend hours every day feeding out. “But then in the weekends, we head to Round Hill as a family and go skiing for the afternoon,” he says.

Growing up, his backyard was the Cass Valley, a piece of the backcountry popular with hunters and hikers. After correspondence lessons, he and his sisters would head off rabbiting, use sharpened musterer’s sticks to spear trout coming up the creek, or venture further afield on skis or bike.

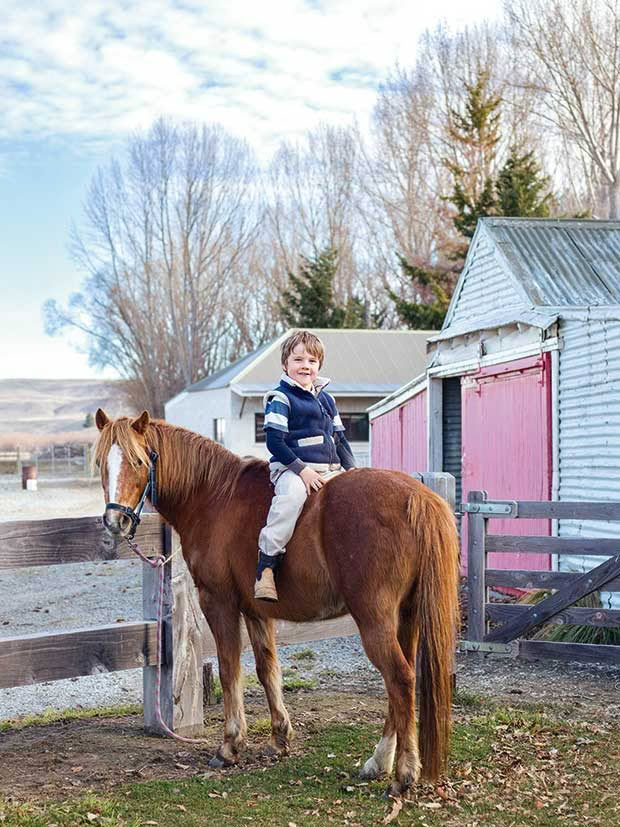

Safe, reliable horses allow the Murray children the freedom to explore Glenmore. Ben rides 18-year-old Milo, Greta is on 16-year-old Houdini and Angus is on 12-year-old Nellie, a station-bred horse with great stock sense. Dogs are the other constant. The family’s three-year-old jack russell Huckle hangs out with Snoop, a huntaway, and Bean, a heading dog

He was six when he experienced his first muster, and at eight was helping during shearing and crutching. Glenmore was the universe.

Today’s Murray kids are just as independent, albeit more socialized as a result of attending play centre and school. All three shot their first tahr at a young age, and they will routinely ride motorbikes or ponies into the valleys on adventures.

Behind Ben and Milo is the old Glenmore workshop (with the red doors) and its contemporary replacement.

“They have an incredible amount of freedom, but they’ve also been raised with the knowledge of how to look after themselves, and to love and enjoy the outdoors. It’s a big focus for us,” says Ems.

Will has a tradition of taking each of the children individually up the Cass to camp under the stars, and in 2013 the family built a ski touring hut — having fun with the snow rather than constantly battling it is a wintertime sanity-saver. Not that they can ever switch off.

“Glenmore is a big business, and it’s sitting on two sets of shoulders — some companies of this size would have a board of directors,” Ems says.

Mixed-aged Angus cattle on Cass Flat. Will’s father Jim Murray introduced the Angus breed to Glenmore, and Will and Ems now farm a herd of 450.

Their biggest call was to replace the farm’s border dykes with an ambitious centre-pivot system irrigating 300 hectares. Pivots grow more grass and use less water — the profligacy of border dykes meant the old system was never going to be sustainable — but they had to borrow a formidable amount of money.

“We couldn’t see how we could farm our way out of that,” says Will, adding that a farm adviser helped them calculate how the investment could work. “It gave us the confidence to charge on — and the development is working out better than we thought.”

Ems routinely cooks for large groups — contractors and other farm visitors, shepherds, and so on. In the lead-up to the autumn muster, she’ll prepare enough food for eight musterers for a week, all packed into army tins.

They are getting more production off the good soils, and are now able to finish lambs. Crucially, the new irrigation means a guaranteed supply of quality winter feed. “We’re both loving farming — we’ve never loved it as much as we do now.”

Another change is the partnership they’ve formed with high-end Norwegian merino clothing company Devold. “It’s exciting,” says Ems.

- The homestead fireplace is made of Glenmore riverstones. The tahr trophy head above the mantle was a New Zealand record, gifted to the Murrays by a hunter friend.

“Our wool will go right from sheep to shop, and every garment will have a swing tag with our name and story. Will and I were wanting to build that sort of relationship with a company, one with real depth.”

The Devold contract is a vote of confidence in Glenmore’s future, yet farming in this part of the world is an “unpredictable” undertaking, says Will, not least because of increasingly polarized views about its future in the Mackenzie Basin.

The Murrays have been proactive, voluntarily fencing off waterways and planting riparian margins before it became mandatory, and routinely testing water quality. (Lake Alexandrina, on Glenmore’s border, is officially a sensitive catchment.)

“We’re not perfect, but we do our best, and we’re environmentally responsible,” says Will, adding that various battles over the years have only deepened his attachment to Glenmore and the Mackenzie.

For Ems, it was having kids that allowed Glenmore to get under her skin. “The sheer privilege of bringing up our children in this environment, despite all the challenges, is what makes it home for me,” she says.

Their ultimate goal is to keep Glenmore in the family, assuming the kids want to take it on. As part of succession planning, they now rent out both ski huts. Being so close to Tekapo, there are sure to be other tourism opportunities.

“Looking ahead, we think tourism could be more lucrative than farming, and if one of the kids wanted to run that side of the business, they could,” says Ems.

The Murrays erected their second ski hut in 2018. Called the Falcon’s Nest, it was built at 1500 metres near the head of Tin Hut Creek, a three-hour hike from the valley floor. About half of the visitors helicopter in, which means a bonus ride to the top of their first run.

That’s well down the track. For now, the family just want to enjoy this magical piece of the high country. Will, who never seriously contemplated doing anything other than farm Glenmore, certainly hasn’t lost his love of the place.

“We don’t like to romanticize it,” he says, “but you go away and when you come home, it really does take your breath away.”

The hut is ideally located, with skiing right to the doorstep, although the wires holding it down indicate just how strong the winds can blow. Will, a keen mountaineer, got Ems into ski touring when early in their relationship he took her on a trip to Aoraki/Mt Cook National Park. HUT IN THE HILLS

Nothing comes easily in the high country, and building huts is no exception. In the case of the Lady Emily, the Murrays’ original backcountry ski hut, everything had to be choppered in. It was worth it: set 500 metres above the Cass Valley, the hut looks directly at Mt Hutton and the Faraday Glacier.

- Looking towards the head of the Cass Valley and Mt Hutton. The children’s toboggan was from a second-hand shop.

- “Our goal is that they will be able to ski any terrain, and enjoy the backcountry,” says Ems

- Angus and his siblings do a fair bit of ski racing at Round Hill and other fields. Last winter, Angus went ski touring with his parents for the first time; eventually, Greta and Ben will follow.

- Note the wooden trusses and tin roof. The handle is to help family and guests swing up into the top bunk.

“And if you’re up on any of the passes you’ll see Cook and Tasman,” says Will, who built the hut initially with family holidays in mind. “It was all about being in the mountains and enjoying the isolation.”

Ben and Angus inside the Falcon’s Nest. Will’s attention to detail includes drying racks and a boot stacker. Will wanted to create a hut with an authentic feel.

So much for that plan. Since the Murrays made the hut available to paying guests, they’ve had to book themselves a spot every winter — “and quite early, too, because it gets so busy”. Last year, they added a second hut, dubbed the Falcon’s Nest because of its eyrie-like setting.

The two-room Lady Emily sleeps 10 and has a similar look and feel to the Falcon’s Nest. The Murrays always try to get at least two trips up to the hut in winter. “Even if it’s just for a couple of nights and three days, that’s a trip in our minds,” says Ems.

“It’s some of the best ski touring in New Zealand,” says Will of Glenmore’s terrain. “But you have to be pretty careful with avalanches, and you need to be reasonably experienced — or take a guide.”

CALL TO ARMS

Glenmore is one of a vanishing few stations that still run an autumn muster, and it’s done old-school-style — no helicopters, no horses (the terrain is unsuitable), and no shortage of craic in the huts.

Mustered ewes in one of the Cass Valley’s lower winter blocks. Their wool is destined for Norwegian garment-maker Devold, who will highlight the provenance with swing-tags telling the Glenmore story. “We put so much effort into our stud and producing quality wool, and it’s so satisfying to be recognized for it,” says Will.

During the long days, a team of eight musterers and dogs walk sometimes-treacherous beats, winkling out sheep from the bluffs above the Cass River.

Ems still helps on the odd day, but hasn’t done a full five-day muster since the children arrived.

“It’s one of the best weeks of the year — the storytelling at night, walking those hills. I’ll probably get back into it when the children are grown up. I miss it.”

For Will, the appeal has never waned. “Part of it is the four good friends who turn up every year to muster with the Glenmore shepherds — you muster seriously but have fun at night.

“There’s a sense of relief, too, getting the sheep down before the snow comes, knowing they’re safely out of the hills.”

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.