A guide to pedigree, purebred, heritage and hybrid chicken breeds

There are purebreds, heritage breeds, hybrids, strains, crossbreeds and ‘barnyard specials’ which can make it hard to work out exactly what kind of bird you have.

Words: Sue Clarke

A breed of poultry (or any species) is a group which all bear similar characteristics and which will breed true generation after generation. This might mean they all have the same comb type, the same number of toes, the same style of feathering and the same body shape. While people may call a pure breed chicken ‘pure’ because its two parents looked to be the same breed, unless accurate records are kept going back over several generations (at least five) then you can never be sure that another breed was used, either by accident or intent, in either of the parents’ ancestors.

PEDIGREE

“…the record of descent of an animal, showing it to be purebred.”

PUREBRED

“…of or relating to an animal, all of whose ancestors derive over many generations from a recognised breed.”

A particular breed will have what is known as a Breed Standard, and this is true for dogs, cows, sheep and poultry. This is where a group of fanciers have sat down and written a formal standard to which all animals in that breed should conform to.

From time to time they may adjust the standard to more accurately describe the type they would like the breed to conform to. You only need to see photos of a particular breed of dog, cat or cow over the past 70 years to see how our idea of what a particular breed should look like, or what fashion, and/or the show ring dictates it should be, has changed.

Polish rooster.

Sometimes another breed may be added into the mix to make a slight change to it. This is a common technique breeders use when a new colour is desired. If a serious fancier wants to develop a colour or breed which may exist overseas but not in NZ (because it’s almost impossibly expensive to import poultry into NZ for biosecurity reasons) then they will need to create a population of birds with the attribute, then breed several more generations until they are certain that the new physical appearance is breeding ‘true to type’.

Some breeds have fallen out of popularity or even died out completely. It may be possible to use other breeds to recreate similar-coloured and similar-shaped birds that look like the originals, but one of the consequences of doing this is the small gene pool it creates. To try to create a true-to-type bird means constant inbreeding which leads to a reduction in reproductive ability, especially if no selection is done specifically for it (because a breeder is usually concentrating on colour or shape instead).

White Silkie

Males become less fertile and females lay fewer eggs, which may have very poor hatchability due to a weak germinal disc (the white spot on a yolk that contains the female’s DNA contribution) and the male’s inability to fertilise them. This adds to the difficulty of preserving the breed and inevitably new blood from another but similar breed may have to be added to improve the survival rate.

HERITAGE BREEDS

Purebreds are tending to be known nowadays as heritage breeds. These are poultry breeds that have been in existence since many were first established back in the late 1800s. Since then, many colours and varieties have been added to the original basic breeds.

Pure breeds all have their own special characteristics, and it’s important to preserve them for the future in case their particular specialities – for example, five toes, blue eggs, broad breasts, long legs, lack of broodiness – are needed for future breeding developments.

SEX-LINKED BIRDS

Certain characteristics, like the colour of the chick down and the rate of growth of the feathers from one day old, are governed by genes. If those genes are carried on the sex chromosomes you are able to differentiate the sex of the chicks at hatching provided you cross two breeds which have the pure gene for the opposite condition. For example, you can create chicks that hatch with red-gold down (girls) and silver-white down (boys), or it could be one sex feathers up fast (girls), with feathering beginning within a day of hatching, and slow (boys), with no feathering evident.

In fast feathering, primaries erupt on the edge of the wing and are usually at the ‘paintbrush’ stage of opening, and are much longer than the secondaries that erupt further back on the wing.

This is how commercial breeding companies can easily and cheaply sex newly-hatched chicks and only sell the pullets (females) and either dispose of or fatten the males.

One of the most common methods uses Rhode Island Red roosters and Light Sussex hens. A purebred Rhode Island Red male carries the gold gene (ss) on his two sex chromosomes, and he can only pass on gold colouring. A purebred Light Sussex hen carries the dominant gene for silver (S-) and only has the one sex chromosome, which means she can only pass on silver colouring. Their chicks can either be (Ss) which would be silver males with yellow fluff, or (s-) which would be brown females with ginger fluff (as they only have one sex chromosome and the only gene from their dad is gold).

Other sex-linked crosses include ones where the father carries the gene for fast feather development (kk) which is characterised by early development along the wing edges at hatching and the mother carries the gene for slow feather development (K-) on her one sex chromosome, and the wing feathers have hardly erupted. This sex-linked cross is often used in the broiler meat chicken industry to sex chicks that are then fattened using different feed regimes according to their sex.

Overseas there are still some sex linked crosses of pure breeds available commercially. The Black Rock (a cross of a Rhode Island Red rooster over a Barred Plymouth Rock hen) uses the barring gene for sexing. The barring gene typically produces chicks with or without a white spot on their heads.

Male and female chicks can be sorted by colour at hatching if it’s possible to use sex-linked genes.

The ‘Golden Comet’ is another sex linked cross of a Rhode Island Red rooster over a White Leghorn hen which uses the gold and silver gene.

While anybody with these breeds could produce chicks which are able to be sexed at hatching, commercially-produced birds have been developed from strains of the breeds that have been selected for their egg production and type, as well as the parents also breeding true for the desired down colour of the chicks. It has taken decades of highly-funded breeding programmes to produce well-rounded birds, and access to good quality birds to start with.

HYBRIDS

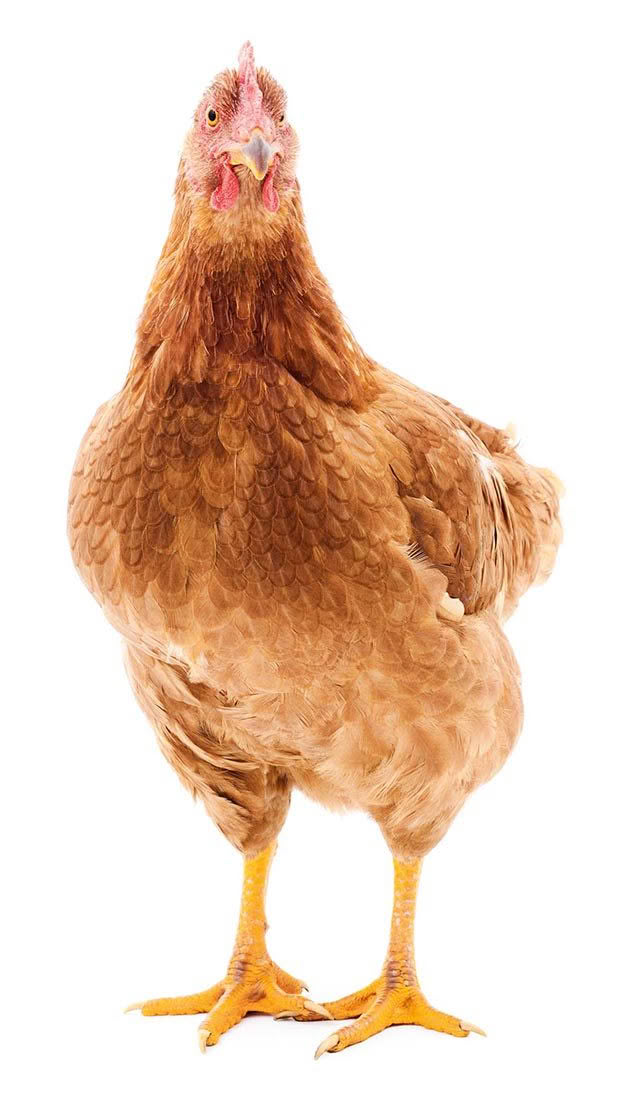

Nowadays when we talk about ‘chickens’, we’re often referring to the brown hybrid birds used on commercial farms.

Hybrid birds have been developed over many generations from pure breeds (eg, Leghorn) but are so advanced, they are now a mix usually just of ‘lines’ denoted by numbers or letters. Some hybrids are actually just produced by crossing very productive strains of one breed.

The two international companies that supply hybrids in NZ are Shaver and Hyline which sell day-old pullets.

LAYER HYBRIDS

There are many White Leghorn-type commercial hybrids on the market around the world, developed by different breeding companies and called by different names or numbers. The Shaver 288 was a White Leghorn cross that used to be available in NZ up until about 10 years ago. Hyline also had a strain cross based on the White Leghorn, known as the W98.

Neither of these birds is now available. Sometime in the 1990s, the NZ public began to prefer to eat brown-shelled eggs and so now all commercial layer hens are brown- feathered and lay brown eggs. The white hybrids are still available overseas where white eggs are preferred by consumers.

The brown-feathered hybrids available in NZ today are called the Hyline Brown and the Shaver Brown. Both are light-weight, feed-efficient birds which lay brown- shelled eggs and have descended from slightly different crosses of both white and brown breeds over the years. The companies that supply these birds hatch millions of eggs a year in NZ, and can sex the chicks just by looking at the colour of their down.

The father carries the gold gene (ss) which he passes on to his daughters, which hatch with ginger fluff and grow on to have brown adult feathers. The mother is a small, mainly white bird that lays brown eggs and carries the silver gene (S-) on her one sex chromosome. Male chicks are (Ss), with one gene from each parent, have yellow fluff and mainly white feathers with brown shoulders when an adult.

Brown hybrid birds used on commercial farms.

MEAT HYBRIDS

Meat chickens are usually all white-feathered and have also been developed over many years. The commercial companies that created these hybrids originally used strain crosses of different heavy breeds such as Cornish Game, Light Sussex and White Plymouth Rocks.

Male and female chicks of this hybrid fatten at different rates, so the companies used a naturally-occurring feathering gene to ensure a cheap and easy method of sexing. They first had to make sure the two parents were ‘pure’ for either slow or fast feathering, which is known to be inherited on the sex chromosome. This method can only be done with certainty in the first day or two after hatching.

BARNYARD ‘SPECIALS’

These birds can be any breed, layer, meat, heavy, light, bantam and are what you’ll see in most backyards. People on poultry Facebook pages and other places online often post images of very handsome birds asking what breed they are, but usually they cannot be assigned to any one breed because they are crosses of crosses.

You can take a Shaver or Hyline hen and cross it with a cross-breed rooster and create hens which are excellent layers. They may even look like their brown-feathered mother. However these cannot be sold as Shavers or Hylines as they can never repeat the productivity of the parents of the original hybrid, and the company names are trademarked.

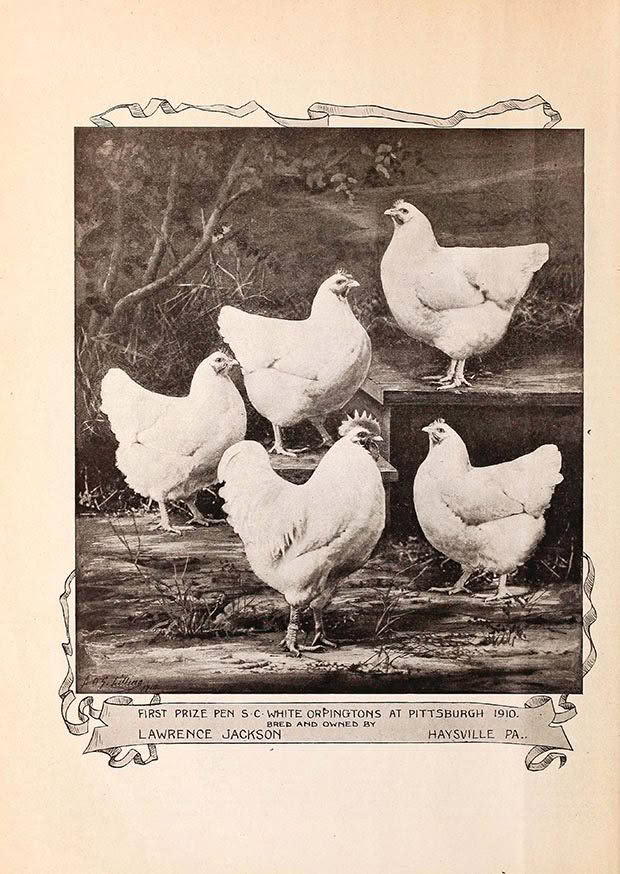

ORPINGTONS VS AUSTRALORPS

Champion Orpingtons from the USA, 1910.

The Orpington was bred to be the perfect bird for the self-sufficient farmer, a good layer but with good meat production too. It was named after Orpington in Kent and was created over about 10 years in the 1880s by commercial poultry farmer William Cook. His business sent thousands of birds all over Europe and he wanted to create the perfect utility bird, one that would lay high numbers of eggs (over 300 a year) and still provide a good meat source.

The Orpington breed quickly became popular, and was soon a meat bird of choice.

Orpingtons, 1885

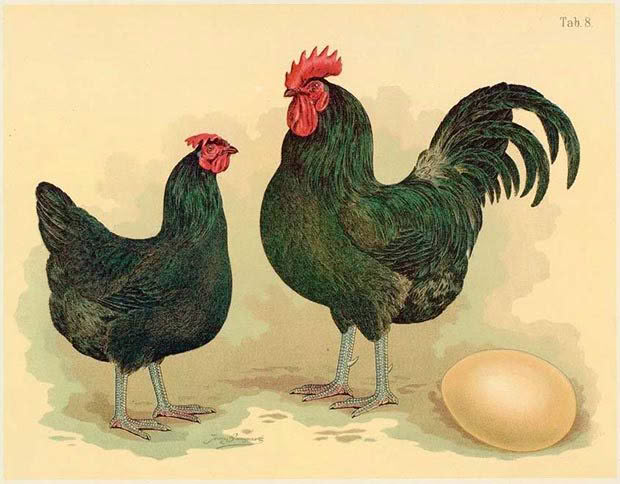

In the late 1800s, Orpingtons were imported into Australia, but local breeders found they wanted a bird that was a better layer. They began crossing the Orpington with Minorcas, White Leghorns and Langshans to try and improve the laying ability. The result was a bird they called the Australian Black Orpington, or the Australorp for short.

By the 1920s the Australorp was winning the big egg laying competitions, and poultry owners around the world were clamouring to have it in their flock. In 1929, it was decided to recognise the breed in its own right.

“It was the egg-laying performance of Australorps that attracted world attention when, in 1922-23, a team of six hens set a world record by laying 1857 eggs for an average of 309.5 eggs per hen during a 365 consecutive day trial (without the benefits of artificial lighting).

“A new record was set when an Australorp hen laid 364 eggs in 365 days.”

Source: Wikipedia

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.