How Gaudi inspired Fred van Brandenberg’s design for the 120,000 square metre Marisfrolg building

A revelation, which came like a bolt from the blue, turned an experienced and successful architect away from the traditional styles in which he’d always worked towards something far more organic.

Words: Nathalie Brown Photos: Rachael Hale McKenna

Lake Hayes-based architect Fred van Brandenburg first saw the groundbreaking and structurally defiant work of Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí while he was studying architecture at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg in the early 1970s. At the time, the young South African was spending his university holidays in Spain.

- How to beat the empty nest syndrome? Get papillons and a samoyed. And a cat. (From left) Keisha the samoyed, Fred with his favourite papillon, Poppy on his lap, Gemma on Dianne’s knee, Polly on the couch and Kia on the floor.

- The bedroom pavilion is separated from the living area by a bridge over tranquil water.

- The bedroom pavilion is separated from the living area by a bridge over tranquil water.

- Fred designed his home in a series of pavilions connected by bridges and flat-roofed passages.

- Every second Saturday afternoon, up to 18 women arrive and take over the living and dining areas as well as Dianne’s studio in a multi-layered sewing spiral.

- Dianne recently photographed Dunedin’s street art, transferred the images to fabric and is re-interpreting them as multimedia pieces.

- Dianne spends most of her afternoons creating expanses of fabric art.

- Jude laid the stones in the pathway leading to the stained-glass front door, made by a South African artist.

- The family created ponds and planted maples, rowans and liquidambars for autumn colour.

- Fred believes landscaping is almost as important as the house design.

- The family created ponds and planted maples, rowans and liquidambars for autumn colour.

- Chilla the cat patrolling the ponds.

But it wasn’t until his return to that country in 2004 and his visit to Park Güell in Barcelona, designed by Gaudí in his naturalist phase (during which Gaudi was inspired by organic forms from nature), that Fred had a Gaudí-inspired revelation.

“It was an architecturally cathartic experience,” he says. “It struck me like a thunderbolt. In a fleeting second I knew I needed to learn more about these structural principles, to see how I could adapt them and use them in contemporary architecture, to let the structure become the architecture. I was overcome with emotion and dashing tears from my eyes.

“I was enthralled by Gaudí’s organic forms; by the spaces, the engineering principles and decorative motifs. I saw structural solutions created by intersecting forms that seemed spontaneous and natural while being controled by what I later learned was schoolboy geometry sourced from nature.”

Fred made an immediate decision to abandon the straight lines and single facades of mainstream architectural design in favour of the forms found in nature.

“I thought, ‘My work is so mundane, I should be ashamed of myself.’ I had stopped pushing the boundaries. If Gaudí can do this back in the late 1800s then there is no excuse for me. So I went home and ceremoniously ripped up my past work. You can imagine the expression on my wife’s face. So how am I going to feed the family? Never mind… I’ll find a way.”

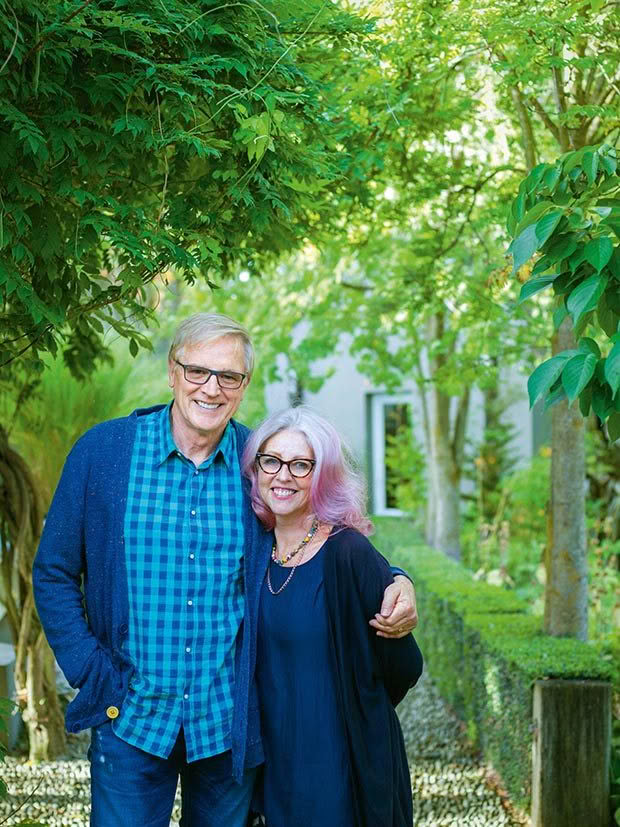

Fred and his wife Dianne had emigrated to New Zealand in 1988 with their four sons Patric, Damien, Jude and Luca and settled in Queenstown. Says Fred: “I had made up my mind to leave apartheid South Africa many years earlier and since I knew I had to start all over again regardless of location, why not choose beautiful Queenstown?”

After his arrival in New Zealand Fred had become well known for his work on several leading New Zealand resorts. He was the founding architect for Millbrook in Arrowtown from 1989 to 1995, the principal designer on Huka Lodge near Taupo for 13 years and he designed luxury lodge Wharekauhau in the Wairarapa, basing it on the high-end arts and crafts style of the British architect Edwin Lutyens.

“At the time, I saw architecture for second homes and lodges as a stage set – a piece of theatre for tourists who wanted to be taken away from their real life and brought into a fantasy world. Wharekauhau took this to an extreme.”

Within weeks of his return to New Zealand after that pivotal trip to Gaudí’s Park Gull in Barcelona, Fred was with a client for whom he had recently completed the design of a large house. Fred told his client that this design was to be the last of the old van Brandenburg style. The client told Fred he didn’t want to have the last of the old style but the first of the new.

“So I said he would need to come with me to Barcelona to see Gaudí’s early work, with its relatively simple geometry.” And while in Barcelona with his client and simply by chance, Fred met the great Gaudí exponent and then director of the Royal Gaudí Chair at the School of Architecture at the Polytechnical University of Catalonia, professor Juan Bassegoda Nonell. The professor was teaching postgraduate architecture students in a small faculty located in Finca Güell – the Güell Pavilions.

“I was looking for a way through the gate into the pavilions, so I slipped in while someone was going out. I did not know what was in the interior and sheepishly found myself in the presence of professor Bassegoda, the wonderful man who was going to change my life.

“I went back to Barcelona six or seven times in the next several years and every time I made an appointment to see him. He would look up from behind his pile of books and would greet me: ‘Ah… Mr New Zealand. You are back again.’ And he would give me an hour of his valuable time.” The professor died in 2012 and Fred has since met his successor.

“After the first few times listening to professor Bassegoda I began to understand that Gaudí was a brilliant architect but an even more brilliant engineer. It was the engineering part that fascinated me because I knew that if I learnt that geometry and applied it to my new architecture it would free me up entirely.

“When we did the cost estimates for the first client in my new way of working, the house proved to be less expensive to build than the one I had designed for him before I experienced my epiphany. It proved that this wild architecture was cheaper than the conventional architecture. That gave me the confidence to know that as long as I stuck to those geometric principles that I learnt from Gaudí, everything was buildable.”

Fred says all buildings should tell a story with their architecture. “Forms found in nature are easy to see, and this is our natural heritage. But we also need to reflect our cultural heritage and by this I mean the communities that existed before the white settlers arrived. For example, in the Crest hotel project (on the shores of Lake Wakatipu) we have designed retaining walls that are sculptural metaphors for wakas that would have been on Lake Wakatipu.”

It makes good economic sense, he says, for Aotearoa architecture to be exuberantly creative because international visitors are looking for something uniquely New Zealand.

Today Fred’s practice, Architecture van Brandenburg, is designing the massive Shenzhen headquarters of Chinese fashion label Marisfrolg. The building, on an island site of 5.5 hectares with a 120,000-square-metre building (12 times the size of Te Papa), is said to be the largest contract yet undertaken by a New Zealand firm in China. Drawings began in 2007, work commenced on site in 2010 and Fred expects the project to be complete in another three years.

“This project was simply gifted to me,” he says. “I did not need to bid for it. The owners heard about me when they toured New Zealand and visited some of the lodges where my name kept cropping up. When I told them I no longer did this style of architecture, they were not fazed. But they do rely on me to design it in the most cost-effective way possible. This is a responsibility ingrained in me a long time ago: do everything to get the best result for the cheapest cost.

“Nearly half the building is underground with controlled shafts of natural light to the bottom floors. Just recently the building emerged from the ground and, with the scaffolding coming down, only now can we see the full extent of the design. And to think that all this is done by a handful of my talented staff out of New Zealand.”

In the van Brandenburg design studio in Dunedin, Fred’s “talented six young designers” work to the philosophy that if they can’t build something in a model, a builder can’t be expected to build it in real life. Fred says it is a very simple philosophy. The designers begin with small, rough, mock-ups in a physical form, rather like the way a sculptor works. Many models are made and rejected before they arrive at the right one. This perfect model is then drawn in CAD and printed with a 3D printer. This allows the form to be assessed for accuracy to the millimetre before it is converted into 2D drawings for construction. This is the reverse of most architectural processes in which 2D drawings are converted into buildings.

And where to from here? “I’m like many architects who really only hit their straps in their 60s and 70s. I’ve just started. There’s so much more to do in my work. What I saw on that day in 2004 was the source of a change in me, like an unfurling. I’m still growing.”

THE CHINA PROJECT

Shaz and Fred confer on the surface treatments for aspects of the China project; a model of the Marisfrolg headquarters; details of the China project under construction.

Seen from the air, the Marisfrolg Headquarters in Shenzhen, China, could be a bird in flight. Visitors strolling around the enormous complex will discern different natural shapes everywhere. This is Architecture van Brandenburg’s most ambitious project to date: a construction that covers 120,000 square metres of low lying, interconnected buildings located on a 5.5-hectare site.

The headquarters of one of China’s leading high-end fashion labels, it includes an art exhibition centre, boutique hotel, restaurants, cafés, retail stores and a catwalk and event venue.

“Recycling and repurposing of materials is an essential part of the design and construction,” says Fred. “A team from the construction site in China goes to factories to collect marble and granite offcuts, ceramics from potteries and glass slag from glass-blowing factories. The materials are inserted into the building’s surfaces. Two of my staff from the Dunedin office have set up workshops to teach the construction workers how to apply the recycled material as mosaics and the like, so they are learning new skills which they can take with them to their next contract.”

THE ‘OLIVE LEAF’

The architectural model of Fred’s proposed community centre alongside St Patrick’s Catholic Church

Arrowtown is split on this one. Fred, a committed Catholic and a member of the local parish, has offered his services pro bono to design and fundraise for the building of an ultra-modern community centre on church land alongside the 1873 St Patrick’s Catholic church.

The architectural model of his proposed community centre, with its olive leaf-shaped roof, sees it built largely underground as if genuflecting beside the church. The profile ensures the historic building’s prominence. “My idea is to make it a venue for community activities for the entire population of Arrowtown and beyond,” says Fred.

While he has support, there are some in the parish and wider community who believe that any structure renovated or built anew in Arrowtown must look as if it were built in the 1870s.

Fred is fired up about this. “The 2006 and 2016 Arrowtown design guidelines support my concept. Moreover, we should pay homage to our pre-miner cultural heritage too. The design complies with the district plan so there should be no argument about it.” He and his team are currently preparing for resource consent. vanbrandenburg.co.nz

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.