Game on for Lumsden salami business

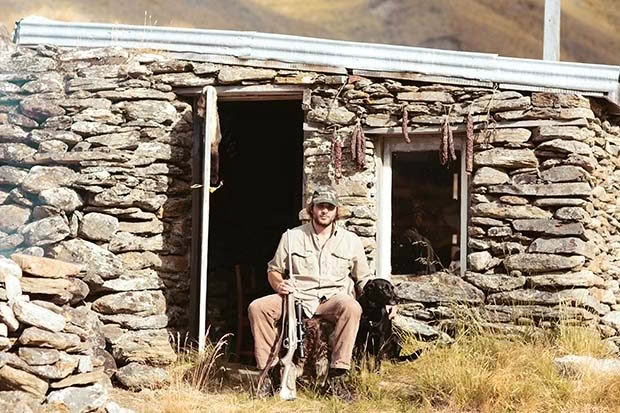

A passion for hunting and a taste for cured meat prompted Chris and Sally Thorn to start their own artisan business in Lumsden.

Words Anna Tait-Jamieson Photos Rachael Kelly

The ripening room at Chris and Sally Thorn’s Lumsden factory is filled with the aroma of cured meat. The umami fragrance emanates from a hanging regiment of salamis, lined in rows according to age and progressing in colour from brick brown to powdery white. The white comes from the naturally occurring bloom that denotes a traditionally made, dry-cured salami.

These are wild game salamis, made with venison shot by professional hunters in Fiordland National Park. Each will be packed for retail with a reference number linking to the company’s website, allowing consumers to track their salami back to the deer itself. It is the ultimate in traceability.

A satellite map on the website zooms in on the exact location of the deer when it was shot, the weather conditions at the time, the name of the hunter and the calibre of the bullet that felled it. Too much information? Not if you care about where your meat comes from, and not if you’re a hunter yourself.

Chris started hunting at 14, targeting rabbits and goats with a bow and arrow because his father wouldn’t let him have a gun. By 16 he was an international bow-hunting champion and his hobby had become an enduring passion. These days he hunts deer in the tussock near the home he shares with Sally in Te Anau. Sometimes she joins him to help carry out the meat, but mostly it’s a solitary experience.

“It’s my peaceful time. When you’re walking up in the hills you zone out. It’s almost like meditating. Your mind is focused on one thing, which is very irregular for me, so it’s a great way to relax.”

It was his success at hunting that set him on the path to salami – in the sense that if he hadn’t been such a crack shot he wouldn’t have had to come up with ever-more interesting ways to deal with the abundance of meat he had. Fed up with steak, stir fry and schnitzel, he first of all learned how to make jerky and then moved on to salami.

By salami, he means proper fermented, dry-cured salami, not the cooked version beloved of game butchers.

“We call that dog roll. You take your meat to the butcher and say you’d like salamis made and you come back with dog roll. You think, ‘Why am I eating this stuff?’ That was the big one behind the business decision: why are we putting up with salami like this when we could be making proper salami?”

A business that combined his passion for hunting with his growing interest in curing techniques made perfect sense, and if he could strike a blow for conservation by creating something of quality from a pest species, then so much the better.

His first attempts were guided by YouTube and taste-tested by Sally and various friends. Their feedback encouraged him to give up his job with Shotover Jet and concentrate full-time on his recipes. The breakthrough came when he and Sally took a research trip to Italy where they joined her extended family for their annual salami-making event. Chris recalls a crazy festive affair with lots of food, wine and banter.

In the midst of it all he took copious notes, working out ratios from ingredients that were thrown in by the handful, and asking endless questions of the men in the family as they minced and pounded the pork for their traditional Calabrese salami.

His own product is made from venison mixed with 18 per cent pork back fat, a necessary addition because venison has little fat of its own. The meat is coarse-cut and flavoured with herbs and spices. Sodium nitrate is added to protect against botulism, and a culture is introduced to kick-start the fermentation process.

Chris flavours his salami with cayenne, fennel, chilli, allspice, juniper – “anything that goes well in a gin goes well with venison”.

The salamis are aged and ripened in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room for up to 11 weeks, during which they are inspected daily and wiped down in much the same way as cheesemakers look after their cheese.

The result is a salami with a rich gamey flavour and a sweet lactic tang. The flavourings are robust but not overwhelming and the dense chewy texture is countered by the silky mouth-feel of pork fat.

It’s a quality product but it comes at a price. That’s largely because wild venison costs much more than farmed, and salami loses half its weight as it ages. Game meat is also more costly from a regulatory point of view, attracting a battery of tests that add to the already onerous requirements of processing uncooked meat.

On top of all this, Chris admits he underestimated the labour costs of artisan production. “I’m hand-mixing every batch and monitoring the salamis as they dry, and that is such a labour-intensive process. “Every salami is looked at 50 times and handled 50 times before it’s sold.”

They could cut corners but that would be a mistake. Sally, who has taken charge of sales, says the biggest thing she’s learned is not to doubt the product.

“It’s high-end and there are always going to be people out there who say it’s too expensive.”

Despite some resistance, she’s encouraged by the feedback from in-store tastings, especially in Auckland where she says people are less familiar with wild venison. She’s further buoyed by the fact that in little more than a year since they launched, the Gathered Game range of salami and beer sticks is listed in more than 50 stores nationwide.

Like any small business, it’s a work in progress.

Chris says he would love to sell his salamis loose with their protective mould intact, as is the norm in Europe, but it’s a step too far for the Ministry of Primary Industries, which insists on vacuum-packaging.

The constant striving for efficiency and economies of scale leaves little time for relaxation, let alone hunting. Chris, who used to get out with his dogs nearly every day, now blocks out just two days a month on his calendar. Two days in which he can head for the hills, zone out and focus on the hunt.

SALAMI 101

Salami is a fermented, air-dried sausage that is sometimes smoked. Fermentation occurs when beneficial bacteria in the salted meat feed off natural sugars, producing lactic acid that protects the meat from pathogens and gives it a nice tangy flavour. After fermentation, the salamis are ripened and evenly air-dried in conditions that replicate a cool damp cellar. During this time they lose about half their weight in moisture and grow a layer of harmless white mould, which gives further protection from unwanted bacteria and the oxidation that causes rancidity.

A correctly made salami doesn’t need refrigeration unless it is cut and then it should be kept in the fridge and eaten within a couple of weeks. “Salami made in this way usually contains sodium nitrate, an additive that prevents the growth of the bacteria that cause botulism.”

THE BUSINESS CASE

Capital costs: Close to $230,000 for the land, building and machinery.

Production: 100kg of finished product a month – until recently when that figured doubled.

Staff: Chris in the factory and Sally in the office.

RRP: $15 for a 100g salami.

Profitability: “We haven’t started paying ourselves yet but expect to do so by the end of the year.”

Marketing budget: $10,000 set aside on the advice of Chris’s brother Dave, a consultant who helps with financial planning.

Overcoming the challenges: Chris says commercializing the recipes and keeping costs down has been his biggest challenge, followed closely by the difficulties of buying land, building a factory and navigating the regulatory hurdles involved in dealing with wild meat and an uncooked product.

“I didn’t realize how hard and intensive it would be to go through all the MPI stuff and build a factory. We got so overwhelmed with all the paperwork – there were so many times when I thought we’d throw it all in. But we learned to deal with one little bit at a time and we slowly got there. Now the challenge is space. We’re already outgrowing the factory.”

Lesson learned: Believe in your product and stick to your guns.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.