Forty shelter trees to grow your property the best shelterbelt in New Zealand

Good shelterbelt trees are practical, but they can be so much more. Experts from the NZ Tree Crops Association give us their recommendations on some of the best trees for your region, and what to avoid.

What’s the best belt for your lifestyle block? The following are recommendations from members of the NZ Tree Crops Association for Northland, Auckland and Bay of Plenty.

DAVID COLLEY

Tree Crops Association – Northland

Background: macadamia grower, olive grower and processor

Lives: on the Taiharuru Harbour, 20km east of Whangarei

Best shelter picks: Acacia, banksia, oaks

Top tip: a mix of species in multiple rows will always work better and be less maintenance than a single line of something that needs regular trimming

Shelter is one of the most important things to consider when embarking on a horticultural venture, but its value should not be underestimated in a pastoral situation either. There are far too many farms in this country where the stock freeze in winter and bake in summer as they have no shelter.

Oak trees in Hawkes Bay.

On my block, east of Whangarei, near the coast, I have tried several types of trees with varying results. I am a fan of eucalyptus trees but for shelter they have proven not to be a good choice. They are robbers: they take the water, mine the soil of the minerals and their roots extend far from the trunk. The stunted grass growth several metres out from the trees is quite apparent.

Pine trees are ubiquitous, unattractive and can require intensive management.

Banksias are extremely hardy, averse to being fertilised but seed prolifically with seedlings popping up all over the place.

Acacia longifolia (golden wattle) are like a very large shrub producing quite good bushy shelter for a few years, they fix nitrogen like all the Australian acacias, the leaf litter builds up to form a lovely rich mulch under the trees but later in life they become “leggy” and they really only live to around 12 years.

Acacia mearnsii (black wattle) fixes nitrogen, forms good shelter early on in their lifespan but again have a tendency to become leggy and must be kept trimmed.

Poplars don’t like dry and infertile sites to grow well and will sucker so once you’ve got them they can be difficult to get rid of them.

Leyland cypress make good all-round shelter trees, growing reasonably quickly, you don’t have to trim them if space is not an issue (though they will fulfill their shelter function better if they are trimmed).

However, my favourite trees are alders: Alnus cordata (Italian), Alnus glutinosa (black) and Alnus jorullensis (Mexican alder). The latter is an evergreen although there can be a leaf thinning over winter.

Oak trees.

They tend to grow upright, fix nitrogen, form a magnificent mulch under the trees from the leaf litter and action of worms etc, and the roots will go down rather than spread.

If the deciduous varieties are planted closely they can still provide a degree of shelter once their leaves have dropped. The A. glutinosa, if planted very closely, will be able to contain stock when they have reached sufficient density and have been trimmed to form a hedge of about 1.5m in height.

If I was starting again I would do things quite differently. Instead of planting shelterbelts of a single species in a single row around the boundary I would plant in multiple rows (up to four) using a mixture of trees to perform several functions: shelter, food for birds, amenity, resilience.

I’d include a mixture of pittosporums, alders, banksias, other deciduous trees such as oaks, especially pin oaks (Quercus palustris), scarlet oaks (Quercus coccinea) and English oaks (Quercus robur), liquidamber (Liquidambar styraciflua), flax (Phormium tenax), the odd puriri (Vitex lucens), Griselinia littoralis and any other of your favourite trees.

Something like this would provide excellent shelter, plenty of tucker for birds and bees, with the added advantage of looking enormously attractive.

COLLEEN BROWN

Tree Crops Association – Auckland

Background: keen gardener, avid cook, food preserver, wine maker

Lives: Helensville, 40km north-west of Auckland, near Kaipara Harbour, windy elevated site, heavy clay soil

Best shelter picks: hybrid buddleas, Jack Humm crabapples, Osage orange, ornamental flowering cherries, peaches and plums, pittosporums, banksia, callistemons, pyracantha, philadelphus, neriums, loquats, camellias.

Camellia tree.

Colleen’s top tips

✚ Hindsight is a great thing, choose wisely.

✚ The size of your property will determine whether you can plant multiple rows without compromising the available all-day sunlight.

✚ Height can rob you of precious early morning sun in the winter. Be aware that trees planted hundreds of metres away can block those first winter sun rays.

✚ Lovely little gums and poplars will grow into monsters which may then need to be removed.

Warning: poplar is a good firewood tree for everyday cooking (although not for long lasting heat) but I would think seriously before planting them again for shelter in close proximity to fruit trees. They are greedy and thirsty.

Loquat tree.

If you haven’t got any shelter trees yet, curb your impatience and don’t plant any lovely fruit trees until a shelter frame work is set out. If you are planning shelter near to your home consider a mixed planting which is pleasing to the eye. Mine includes bee nectar, bird food, spring blossom and flowers throughout the seasons, crabapples, berries, autumn foliage, deciduous plants and evergreens.

I have also included a few geraniums and rambling roses on the sunny side. Don’t be tempted to plant those roadside rambling roses though; they look stunning in late November, but require controlling.

Banksia tree.

Shelter also doubles as a privacy screen, and separates different areas like the vegetable garden and the poultry area. I am very happy with my feijoa hedge; it’s a good dense hedge, easily trimmed to the desired height and we get lots of feijoas for wine!

Another successful screen/shelter on our block is my elderberry hedge. It’s deciduous, so it’s not so efficient with the winter wind but I always have lots of flowers and berries for culinary use, and it’s easy to quickly establish with cuttings.

NIGEL WESTBURY

Tree Crops Association – Auckland

Background: Amateur ‘anorak’/plant collector with interest in subtropical fruit and heritage cider apple trees

Lives: 99% in Auckland, 1% on 2ha block near Kaiwaka, 100km north-east of Auckland

Best shelter picks: yuccas, kei apple (Dovyalis caffra), tropical apricots (Dovyalis abyssinica), Cattley guavas (Psidium cattleianum)

A rubber tree fights the kikuyu (west).

Nigel’s top tips

✚ My perfect shelter trees: should be easy to propagate, provide potential wind resistance, be attractive (to the eye of the beholder), have a chance against kikuyu, and spread runners/seeds.

✚ Fruit is a great bonus.

✚ Trial and error is the way. Next season I’ll be trying exotics including Seville oranges, Oncoba (O. spinosa) and feijoa.

Cattley guava (eastern side).

Nigel’s warning: Pittosporums are a first choice native, but having previously pruned the top four metres off a 7m Pittosporum eugenioides (lemonwood) I realised that I don’t want to be up a tree with a chainsaw every year.

From a ridge line on my block you can almost see the Kaipara Harbour’s white caps when the westerlies blow. To the east, the Pacific lies scant kilometres away, so I get sea breezes from both directions.

It meant I needed shelter belts to help break this wind, but I also wanted to try for multiple benefits from the trees: food, firewood, stock aversion and attractiveness.

I have trialled yuccas on the windiest sections. The sheep won’t touch them, and they don’t spread or grow outsized overnight. Sure, they don’t give me fruit or firewood but boy, these plants are tough. I put them in as rooted cuttings and whole yucca stems straight into predominantly clay soil and left them to fight through the kikuyu grass.

Yuccas are an unusual choice but doing well (east).

After a couple of years I find they haven’t grown much in height, but they are well rooted and the stems are beginning to look more like an attractive fence. I anticipate that in 10 years they will be 3m-5m high and the trunks will thicken to an almost a solid wall. I will never have to prune or control seedlings.

Kei apples have wicked thorns and can form an impenetrable stock hedge, plus give you interesting fruit that’s good for conserves. The yellow-orange fruit is slightly bigger than a golf ball. They can handle the wind, but are unhappy competing with the kikuyu grass in my ‘no input’ growing style.

The tropical apricot looks more like a plum tree, and I’ve planted this on the easterly slope which reduces exposure from the prevailing westerlies. I have hopes that this will supply me with a crop of intensely sour-apricot fruit for chutney and keep the wood pigeons off my other stone fruit.

Kei apple coming through the kikuyu in Nigel’s ‘no input’ shelter plantings.

Cattley guavas (Psidium cattleianum) are known as robust backyard trees that offer the numerous smaller red fruit or larger, more tasty yellow fruit. I watched with dismay as the whole canopy shed at first, then with delight as the tree burst back into leaf. I now have a collection of seedlings I’m raising for a hedge in a particularly windy spot.

Pears are much tougher than you might think and I’m trialling them on the ridgeline, with apples further down. Pests of these two fruit are assisted by still, damp air in sheltered orchards so hopefully having them on a westerly slope in a steady Kaipara breeze may mean the codling moth and mealy bug will not bother them.

Pears planted on cordon (west).

I’ve also successfully trialled rubber plants (Ficus elastic) – yes, the indoor one – and found it to be extremely tough, with no sign of leaf damage from the wind or sun.

Magnolia grandiflora is definitely a winner.

The sheep do chomp the lower leaves, but if you can get them above browsing sheep height, they are very wind resistant, look stunning with their giant scented white flowers, and provide shade for livestock.

Magnolia (eastern side).

VIV MILNE

Tree Crops Association – Franklin

Background: former commercial orchardist, now home orchard enthusiast

Where: Bombay (50km south of Auckland)

Best shelter picks: Cryptomeria japonica, Italian alder (Alnus cordata), karo (Pittosporum crassifolium), flax (Phormium tenax)

Flax.

Viv’s top tips

✚ Think quality long-term shelter, not so much short term and fast-growing.

✚ The objective of shelter is to slow and dissipate the wind, not block it. If shelter is too dense and blocks the wind, it will go over the trees and ‘dump’ down on what you are trying to protect.

✚ After it’s trimmed, shelter should break about 50% of the wind, while the dissipated air that goes through stops the main air flow over the top descending forcefully. The next trimming must then be done before the shelter closes in to stop more than 80% of the wind.

Viv’s warning: avoid any of the poplar and willow families which send their roots out horizontally and compete with the crop for both water and nutrients.

In the Franklin area (South Auckland, North Waikato), there’s lots of Cryptomeria. It’s an excellent evergreen shelter tree and it has definite advantages. Pinus radiata, macrocarpa (Cupressus macrocarpa) and Leighton’s Green (Cupressocyparis leylandii) are more vigorous.

These all grow quickly to start with but need trimming more often in later life as they grow outwards and upwards. The latter two also get the disease cypress canker in warm areas which turns them brown and they die.

Karo in flower.

Cryptomeria grows mostly upward and a lot less outwards, so it’s slower initially but needs a lot less expensive trimming later. If the preference is for deciduous shelter, the best variety is Italian Alder (Alnus cordata), which has root growth mainly downwards. It will still need trimming.

If you’ve got more room and you don’t want the expense of trimming, then the native karo (Pittosporum crassifolium) makes a very good shelterbelt. It’s not a dense tree like the conifers, so it dissipates the wind, but it will occupy more space. Karo also tolerates salt very well.

Italian alder.

Combinations of trees are good for very strong winds, such as a slope that gets westerlies coming in from the sea. The very first shelter it hits has to be stronger than the other shelterbelts across a block.

Use a multiple row of trees. The first row, nearest the fence could be flax (Phormium tenax) because it’s hugely wind-resistant, and protects the second row, preventing them from being blown over when young as wind doesn’t pour through the bottom.

The next row can be natives like pittosporum or coprosma. The last row can be cryptomeria which is the most wind-resistant of the conifers and can be trimmed on the crop side. This combination gives you a shelterbelt with a progressive slope upwards.

GAIL NEWCOMB

Tree Crops Association – Bay of Plenty

Background: formerly with environmental management company Ecoworks “where we planted just about everything”, NZ Tree Crops historian and archivist

Lives: Katikati, 35km north of Tauranga overlooking river, trees and park that we do not have to maintain

Best shelter picks: Cryptomeria, casuarina, willow, pine, eucalyptus, feijoa, macadamia, pittosporum and other native trees. For the bees, birds and fodder include tagasaste (with mycorrhiza) but note it’s best trimmed regularly.

Pine trees.

Gail’s top tips

✚ Single species shelterbelts need to be trimmed.

✚ Plan the height and distance of your shelter trees carefully. A belt of trees (or a solid fence) will cause wind to compress as it climbs over them. The drop in pressure on the other side then creates a spiral, speeding up the wind and it will drop down a typical distance of about 20 times the height of the shelter. Don’t build your house or plant your special crop in this space.

✚ Take into account wind dump, manageability, consideration for neighbours, council rules, frost on roads, power lines and boundaries.

✚ Maintenance factors include machine access, felling, protection from animals (yours or predators), irrigation in early years, fencing, tree guards.

✚ Evergreen shelter trees should run north to south so shade moves, deciduous trees east to west (note, even bare trees in winter will filter some wind).

✚ The decision on evergreen or deciduous shelter trees will depend on whether your crop needs more shelter in winter or summer.

✚ Some plants do better with specific mycorrhiza (ie, dig up some soil around the base of an adult tree and place it in the hole when planting younger ones).

Gail’s warning: don’t rely on neighbours trees. Properties change owners, needs change, trees grow too big and then you have problems with shading of roads, trees falling across power lines, branches falling on houses and people.

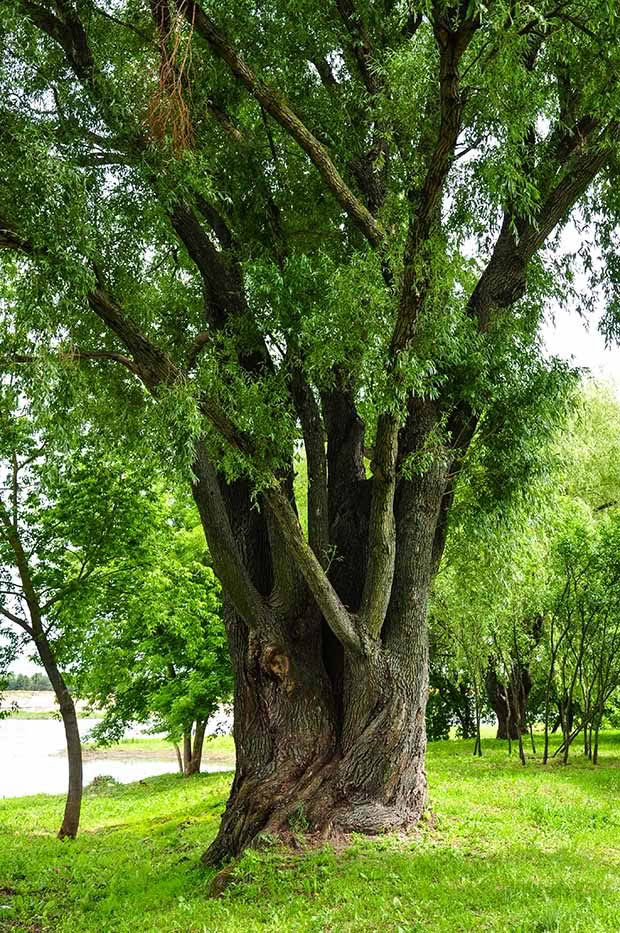

Willow tree.

In the Bay of Plenty most trees will grow taller and faster than they will in most other regions so you need to trim for height control regularly.

Some trees are too good. Our Cryptomeria were a tall, dark wind block that meant wind passed over and was then ‘dumped’ which is not good when it dumps on your crop and/or your house.

If you want nice wool from your sheep then Cryptomeria is not the tree for you. The seed burrs from the trees catch in the fibre and it’s not fun to remove them.

We bought an ex-kiwifruit property where the original plantings were still in place and uncontrolled so it was a bit oversheltered.

We had pines, eucalyptus, willow, cryptomeria and poplars and a lot of trouble finding sunshine. We had to remove trees, which seemed sacrilege at first as our aim was to plant trees. But they have to be the right trees depending on the reason for them.

Willows are fast, easy-growing shelter trees but they were planted with early removal in mind and should have been trimmed or cut down.

Pines are fast-growing and can provide a crop. We actually built our home out the ones we had milled on site, but we got a shock when a disgruntled neighbour came over and threw a bag of avocados at us. She said they had lost their crop to wind.

Karo tree.

“Oh,” I said. “What happened?”

“You cut down the pines.”

By then we didn’t have many trees left so we had room to plant what we wanted and still enjoy sunshine, an outlook and a more permeable wind break. The new owners have removed even more and how lovely it looks.

Think ahead as to how you will manage trees that need to be removed or trimmed. Having a wood-burning stove was great.

We heard much about the advantages of alders and promptly planted some: great nitrogen fixer, good bee food but also lots of little seedlings after a few years, and a multitude of little cones on the paving. It’s a great tree in the right place though.

Macadamia tree.

Then we got the opportunity to plant a bare, flat rural block on the harbour for a friend. His request was for trees for birds and bees and a home orchard.

The east was left open for the views, the north was already over-sheltered by a neighbour’s eucalyptus and more Cryptomeria. That area was planted with rhododendron, camellia, hydrangea and other plants that could cope with shade.

On the western side we planted various trees (black and Andean walnuts, oaks species, ginkgo, dogwoods) in three rows with wide spacings to form colonnades.

The southern shelter is a mixture of evergreens (for privacy) and deciduous with feijoa and other shrubby bushes to help filter the cold SW winds from the central plateau.

A bare paddock was transformed to a sheltered site in a few years, and his fruit trees are cropping well.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.