Follow historical footsteps on a passage through the Australian outback

Heading into the unknown: Silhouette sculptures of the Burke and Wills expedition near the town of Tibooburra.

Following the path of one of the most tragic journeys in Australia’s history comes with insights and similar challenges — minus the need to eat the transport.

Words and Photos: Don Fuchs

Late on a winter’s afternoon in 1860, a grand procession of men, horses, wagons and camels left Melbourne, heading to the Gulf of Carpentaria, 3259 kilometres north. It was the start of an expedition without a clearly defined purpose. Organised by the Royal Society of Victoria, different members had different ideas — from traversing the continent to finding a route for an overland telegraph line.

Fifteen thousand spectators lined the prosperous streets of the British Empire’s second-largest city, witnessing the spectacle of 19 men, 23 horses, six wagons and 26 camels majestically riding out from Royal Park.

The excitement and air of celebration did not foreshadow the great tragedy to follow. Only one man would successfully make the return journey to Melbourne. Seven were to die on route – as were all the animals, most eaten by famished explorers.

A plaque at Camp 119, Burke and Wills’ last camp before the gulf, shows the route the explorers followed and is an appropriate site for an entertaining lecture by Dr Dave Phoenix.

Irishman Robert O’Hara Burke, an officer in the Austrian army and a police superintendent in Australia, led the expedition despite having virtually no bushcraft skills. Burke’s second-in-command, William John Wills, a scientist at heart and a fantastic navigator, was often overruled by Burke. Over time, myths and misconceptions crept into the story of the expedition and Burke’s selection as leader is often seen as a mistake, the expedition as a failure. But despite Burke’s fateful decisions and the expedition’s tragic end, Burke and Wills were the first to cross Australia from south to north, coming within a few kilometres of the gulf. The journey is a cornerstone of Australian history and the country’s folklore.

One of Australia’s foremost experts on the Burke and Wills expedition is historian and author Dr Dave Phoenix. Like Burke and Wills, in 2008, he walked the entire distance travelled by the explorers to gain insight into the trip and an understanding of Burke’s decision-making. Thanks to the Diamantina Touring Company, I am also getting the chance to follow in the expedition’s footsteps.

We are a party of 18 in seven 4WD vehicles. Our departure from Royal Park on a cold and drizzly Melbourne winter morning is significantly more mundane than the original and follows Dave’s first “professorial”, as he calls his talks.

By our day’s end at the first camp in the Mallee country of New South Wales, we have covered the distance that took Burke and Wills 30 days. The 4WDs are parked around the campfire, and while the crew sets up the kitchen, we disappear into the bush to set up our stretchers and swags. A cold night is coming.

From the Mallee, Burke and Wills kept heading north to the Darling River, then Menindee. We visit Menindee’s historic Maidens Hotel, then the last outpost of European advance, where Burke and Wills spent the night. We camp by Lake Pamamaroo, one of several lakes near Menindee.

The famous Dig Tree on the banks of the Cooper Creek is a place of pilgrimage.

North of Menindee, our route leaves that of Burke and Wills for Broken Hill before rejoining it in the Mutawingti National Park. Near the Packsaddle Roadhouse, on the road to the next fixture of Tibooburra in the far northwest of New South Wales, we stop below a hill to look over the flat, arid country to a mountain range in the distance. Behind it is Torowoto Swamp — Burke and Wills Camp 45. Here, “Wright and the two Aboriginal guides turn around and go back, and Burke goes on and tells Wright to follow him up with the stores,” says Dave. “Wright has the weakest camels. He has most of the stores, and he has only six horses. At that point, Burke tells Wright to do something Wright is unable to do, so it’s doomed to failure from the start.” It was a pivotal moment in the expedition as Wright never made it to Cooper Creek with the supplies as planned. It quite likely contributed to the final tragedy.

Late on day four, we drive through Sturt National Park to the Dog Fence and cross into Queensland at the Wompah Gate, one of the few in the 5600-kilometre-long fence constructed to keep dingos out and sheep safe. With the owners’ permission, a trip through Bulloo Downs Station the next day leads to Ludwig Becker’s lonely grave on the banks of the Bulloo River. A German naturalist and artist on the expedition, Becker died on 29 April 1861 of dysentery.

The expedition crosses the enormous Pilpa Moera claypan.

We camp that night on the western side of the Grey Range, which Wills described as “the rugged and stony nature of the ranges” forming a decent obstacle.

The next morning, some of our party follow the first section of the expedition route on foot for a slow view of the country and room for reflection on its challenges. Peter Poggioli, a retired historian and avid walker from Victoria, says striding the dirt roads in the footsteps of a great epic is a trip of a lifetime. A trip he wouldn’t attempt alone even as a 4WD journey.

Near Innamincka on the Cooper Creek in South Australia is the location of the famous Dig Tree. It marks the final, tragic chapter of the expedition. After a gruelling return journey from the gulf more than 1500 kilometres north, Burke and Wills stagger into the camp at the Cooper Creek to find it deserted. Burned into a gum tree on its banks is the message “Dig”. Buried there, the exhausted men find some food. The rest of their expedition had left just nine hours before their arrival.

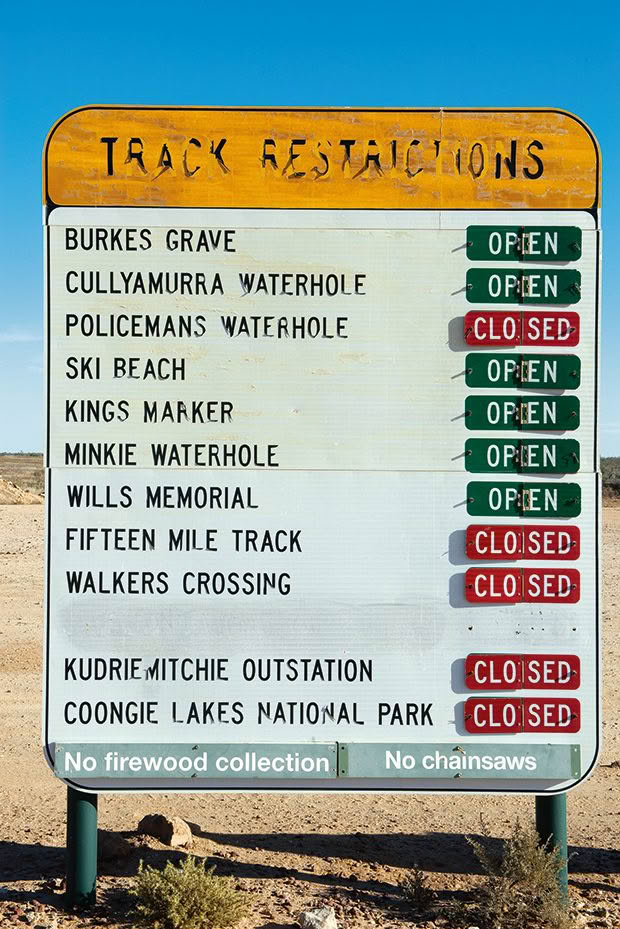

A sign at Innamincka announces a change of plan, with the Walkers Crossing closed due to flooding.

Near starvation and left with two very weak camels, they decided not to follow their old track back to Menindee but to take a shortcut and walk to Mount Hopeless 150 kilometres south. They fail.

We sit in the shade of the famous Dig Tree as Dave talks of the moment of realisation: “They sit on a dune, and then they turn around and walk 50 kilometres back to Cooper Creek. I reckon that point in the dunes in the Strzelecki Desert was the point they know they’re really in trouble.” Burke and Wills die of malnutrition on the banks of the Cooper. Only King, their cameleer, survives. Their graves and other key locations of the final chapter are here in the Innamincka Regional Reserve.

But we are still heading north, past Innamincka and back on Burke and Wills’ outbound route, but this land is never easy. We must invoke plan B as Cooper Creek is in flood, and so we drive via Cordillo Downs and the Cadelga Ruins through the barren Strzelecki Desert to Birdsville.

Our group relaxes along the way to Tibooburra; congregating brolgas are common in the expansive gulf region.

We camp on the Diamantina River south of Birdsville. Recent rains have replenished the river and transformed the flood plains into a green expanse. Birds are plentiful, and night insects drift like snowflakes through the spotlight. I can hear native plague rats rustle in the lignum clumps. Mosquitoes swarm and sting, and come daylight, clouds of flies buzz relentlessly. We are close to Burke and Wills’ 78th camp of the expedition.

“That’s the point,” says Dr Dave Phoenix, “where it can all potentially fall to bits. Leaving the Diamantina, Burke sets off across these massive plains in January with no water. If he doesn’t find water, they either die up there or turn around in time and get back.” They get away with it, find water and continue their journey north.

Physical evidence of the famous expedition barely exists beyond memorials, plaques and blazed trees, yet the harsh landscape speaks loudest of the hardships and incredible determination displayed. The desolation of these relentless plains causes us frequently to ask: “How did they keep going?”

Lake Pamamaroo near the tiny town of Menindee.

On day 13, we visit Camp 119, Burke and Wills’ last and northernmost camp of their outward journey. According to Dave, memorials and blazed trees mark a site that might not be the exact location. From here, they embarked on a last push to reach the gulf, a final dash ending at a tidal salt pan.

We have permission to travel through Magowra Station to see what faced the men and how much they endured. Dave paints the picture: “Plodding slowly and deliberately through the salty mud in hot and humid conditions must have been exhausting. They probably did not go more than a few hours north before realising the futility of their situation.”

The enormity of the Strzelecki Desert swallows the modern expedition.

The enormity of the explorers’ feats floods over us as we stand maybe only metres from where the exhausted men took their last step north. The ocean is still several kilometres away over a shimmering expanse of the saltpan. “Truly the stuff of madness,” says Peter. “I feel in some ways sorry for them, and in some ways intrigued. What were they thinking?”

Burke marked their northernmost point by writing in his diary: “It would be well to say that we reached the sea, but we could not obtain a view of the open ocean, although we made every endeavour to do so.”

ALL ABOARD

The Burke and Wills expeditions start in Melbourne and end in Alice Springs. Participants can choose between taking their own vehicle or buying a seat on one of the company’s vehicles. If you use your own vehicle, ensure it is a well-maintained and proper 4WD with high clearance, two spare tyres and all the necessary tools. Buying a seat relieves travellers from the demands and responsibilities of driving long distances on rough roads in parts, but it can sometimes be uncomfortable due to cramped vehicles.

CAMP: Your bedroom under the stars comes with a stretcher bed and a swag (a comfortable mattress with cosy down quilts covered in heavy canvas). A small LCD light to mark your bedroom in the bush is essential.

CLOTHING: Expect cold nights and sometimes cool/wet days, especially at the beginning of the expedition until the tropics are reached. Pack warm, waterproof clothing, comfortable walking shoes and togs.

CATERING: The trip is fully catered. Bring muesli bars, nuts, chocolate, or other snacks to satisfy cravings during the day.

HYGIENE: All camps are in remote bushland without toilets and showers. There will be occasions for hot showers along the way.

Cost: $9500p/p for a seat or $5600p/p in own vehicle.

Next expedition: 1-17 May

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.