Fiji beyond the golden sands – A writer hikes Mount Tomaniivi

Far-removed from Fiji’s holiday hotspots, a trekking business owned by locals showcases remote villages, mountains and grasslands

Words: Claire McCall Photos: Vantage Fiji, Shahir Daud, Claire McCall

This article was first published in September/October 2018.

The humble wooden sign that marks the summit of Mount Tomaniivi is weather-beaten, carved with graffiti and lost in the past (it says Mount Victoria). The district authority has supplied an impressive new one to grace Fiji’s highest peak. Huge and unwieldly, it languishes still in the ‘base camp’ village of Navai. Those well-meaning folk have clearly never negotiated the muddy trail that rises steeply through sodden jungle to the 1324m peak.

in Nubutautau, trekkers sleep in an authentic bure – the installation seat of Tui Navatusila, an elder of the village, is in the foreground.

This adventure is no cocktail holiday; instead it’s a journey that explores the wild heart of this island nation. It’s the story of golden grasslands, crystal-cool waterfalls, rambling rivers, glassine rockpools, and hills that stretch to the horizon. But beyond that, it is the story of culture and connection, friendship and fearlessness.

When UK expats Matt Capper and Marita Manley came to Fiji in 2006 on a fellowship for the London-based Overseas Development Institute, they thought they’d stay a year – two at most. That was before these hardy hikers were captured by the remote beauty of the countryside away from the tourist hubs on Viti Levu. As they got to know these regions better, and bond with the people who lived in the highlands, they were presented a challenge by an elder of Nubutautau: to help bring other trekkers to the villages of the interior. Marita, an environmental economist, saw the value in sustainable tourism; Matt is a sociable sort who loves to hike. Although they had no previous industry experience and spoke only faulting Fijian, they cherished the opportunity. What better way to combine their talents?

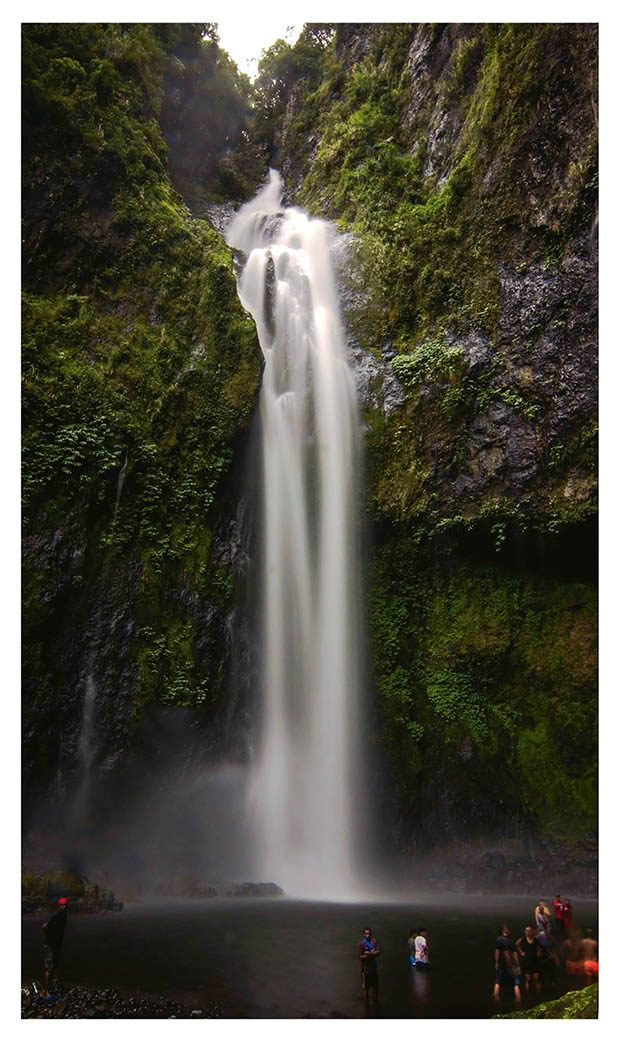

Ferns shade the path to Savulelele waterfall near Nabalesere.

Talanoa Treks is run in partnership with four rural communities and two locally owned lodges. The business offers single and multi-day treks but I signed up for ‘The Full Monty’, a five-day, four-night experience – aka total immersion.

I was joined on the trek by a friend and an American traveler who calls Portland, Oregon home. She’s feisty, dry-witted and 75 years old.

The pristine village of Nabalasere lies alongside a languid river and is the gateway to the Savulelele waterfall. Houses are joyfully painted in pretty teal with burnt-sienna trim. After a gentle stroll for a swim in the waterfall (cold, but not breathtakingly so), we returned to the community hall for our first experience of the sevusevu, a welcome ritual where kava is the focal point.

Guides climb Mount Tomaniivi, Fiji’s highest, in gumboots. A strong hand is always welcome on the muddy, overgrown path to the peak.

Matt gives us a rundown of etiquette: sulus are to be worn within the village boundary; hats removed; it’s considered impolite to walk upright in the hall when people are eating. And, if the muddied waters of the kava are not to our palate, we simply have to grin and bear it.

Although there is the expectation these cultural laws will be adhered to, the kava ceremonies are relaxed and humorous. Over the days, as our little group becomes accustomed to the lip-numbing liquid and the ritual of clapping on receipt of the narcotic root, we notice the locals are having a bit of fun with us. When we ask for ‘low tide’, they surreptitiously swap the coconut cups (which are not uniform in size) for larger ones. It is all done in jest and the laughter that fills the bamboo-walled buildings is genuine and plentiful.

Savulelele waterfall where the water is cold, but not as cold as that in New Zealand.

So is the nourishment. Each night, the women of the village contribute to a shared meal. When any trip to the store is a serious excursion, the immediate gardens, planted fields and nearby rivers provide the ingredients for an organic, mostly vegetarian spread. Plates of taro-leaf burgers, cassava chips, wild greens, fish in coconut milk, aubergine curries, roti bread and sweet yams, appear as if by magic on bright coloured tablecloths lain on the woven mats. We eat in sequence, seated on the floor: visitors first, men second, women and children last. When sitting in the unfamiliar, cross-legged position becomes uncomfortable, I master the art of ‘side saddle’ my legs swept back towards the walls (it is understandably forbidden to sit with feet facing into the feast).

The view from the summit of Mount Tomaniivi makes the effort worthwhile.

After dinner, the evenings are spent in gentle conversation (that’s if the children haven’t appeared like sprites to encourage a game of vindi vindi – a type of pool, played by flicking counters into the pockets with your finger).

‘Talanoa’ means ‘talk’ or ‘stories’ and, with digital silence, these evenings offer a refreshing chance to commune. The tanoa (kava bowl) is oft-replenished: for locals, when conversation reaches a natural pause, it’s the natural time to dip in for another cup. Some say that the propensity for kava drinking makes the men listless – and it’s playing havoc with village life.

Etuate Tesi (left), his son, Pita, Vilitati Rokovesa and Filimoni Nawawabalavu prepare kava for a sevusevu welcome ceremony.

Each night, in the liquid dark, as I lay my head in the community hall, or the lodge, or the privilege of an authentic bure, I fall asleep to the faraway rhythmic clang of the tabili, a metal mortar and pestle used to grind up the root of the kava plant.

Walking in the relative cool of New Zealand is a different story to climbing a mountain in tropical heat: only mad dogs, Englishmen and keen hikers. Mercifully, on the day of our ascent, Tomaniivi has drawn the cloud to it like a magnet. A petrichor scent settles over the jungle as our local guides (always one woman, one man), strong feet planted in gumboots, machete at the ready, encourage, cajole and (it must be said) tug and tow us up the slippery slope. Our septuagenerian colleague has made it. She’s astoundingly fit thanks in part to her membership of The Mazamas, a mountaineering education organization in her hometown.

Pita, ready to charm visitors, in the doorway of the Vale ni Vanua (district meeting hall).

Nevertheless like “the wise women I should now be” she takes a rest the following day and so gracefully misses out on the 12km walk between Naga and Nubutautua.

It’s a day that begins with a haul up grassy hills, turns to rock-hopping along the Sigatoka River and includes a swim in a fathomless blue pool. En route, our guide hacks a couple of gigantic citrus orbs from a tree and at lunchtime, delicately peels the bitter-sweet pink pomelo flesh (moli kana) from the pith with his machete for us all to share.

- Book-lover Etu Tesi was born in Suva but opted to return to a simpler way of life in the home village of his mother, Adi Kaveni.

- Trekkers embark on a 21km hike along the Ba river between Nubutautau and Navala.

- Matt Capper, co-founder of Talanoa Treks, accompanies many of the walks and may even be persuaded to boil water for a hot shower.

Etuate Tesi (Etu for short), headman at Nubutautau, has a heartfelt involvement with the treks. His enthusiasm for the enterprise is deep in his DNA and, in honour of the founders, he has named his youngest daughter Marita.

He tells us the tale of Methodist missionary Reverend Thomas Baker as he leads us to the outskirts of the village across a boardwalk to the very spot where the unfortunate soul and his colleagues were slaughtered and then eaten.

It appears the priestly fellow made a serious error of judgment when he touched the head of the chief (a no-no in Fijian culture) to retrieve a comb he’d lent him that was buried in his hair. An apology from the villagers in 2003 to the good reverend’s descendants was matched by an apology from the Baker family for the lack of respect shown to the chief.

When Etu joins us on the 21km stretch along the Ba River to our final destination, the postcard-pretty village of Navala, he tells yet more stories. He’s the same age as our prime minister (whom he obviously admires), and a voracious reader who devours Zadie Smith, Jonathan Franzen, Chimamanda Adichie. He says Fijians should be proud of their culture and the landscape they often take for granted. Etu also speaks about his decision to leave Suva, the city where he was born and bred, because he felt his life was without true purpose. He returned to settle in his mother’s birthplace and sees the villages as an important safety net for guys like him who lose their way. He has grown into an integral and progressive part of Nubutautau, well grounded, physically and spiritually back on track. Apart from farming, Etu is on the team of trekking guides. Pushing the barrow of more sustainable practices, this new environmentalist is helping to educate fellow villagers about slash-and-burn practices that destroy the very environment they rely on.

- During the sevusevu ceremony, drinking the first bowl of kava offered is pretty much compulsory after which there’s a feast which may include blue cassava-coconut cakes and many vegetable dishes.

- At Nubutautau, interpid trekker Carole Beauclerk (75), is given a lei and talcum- powder blessing by Adi Mere before she sets off.

- In pristine Nabalasere, the houses are painted a tropical shade of teal. Penisoni Naimata leads trekkers to the community hall.

- Once inside the village boundary, it’s courteous to wear a sulu.

Where once he worked in telecommunications bringing voices together over copper wires, now he operates in the face-to-face. One trekker at a time, one foot in front of the other, moving through an ancestral backdrop, he is telling his story but also listening to ours. Turns out walking and talking engenders a timeless two-way connection – this modest pursuit one of life’s great riches.

How to get there: We flew Air New Zealand to Nadi and then transferred with Pehicle from there for a night at Volivoli resort on the Suncoast where Talanoa Treks picked us up the next day for the start of our trek.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.