Everything to know about raising free-range heritage pigs

Free-ranging heritage-breed pigs are intelligent, companionable and productive.

Words: Sheryn Dean

Pigs have been a wonderful revelation to me. I have discovered they are fantastic buddies, and extremely productive.

That’s something the rest of the world has known for a long time. Pigs were among the first animals to be domesticated and farmed. They now account for 35 per cent of today’s global meat production.

I got started in pigs in the best possible way. I bought two weaners in late spring, raised them over summer, finished them in autumn, and put them in the freezer before the winter wet.

Getting two meant they had company. Pigs are very social animals and having just one is cruel. Isolation is a form of torture for humans, and it’s the same for pigs (and other farm livestock too).

Buying two weaners, aged 6-8 weeks, to raise and kill is the easiest way to produce your own pork, but breeding them is the most profitable.

BREEDS

My original two pigs were Large Whites. They grew fast and tasted great. By luck, and a deal involving a kid’s motorbike, my next two were Black Devon (also known as Large Black). I fell in love.

Large Whites are the pigs used in commercial farming. They grow to killing size quickly and produce larger litters than a heritage breed. But they are indoor pigs whose pale skin can burn easily.

Artisan butcher Jono Walker’s heritage pigs on his Waikato farm.

Heritage breeds are more suited to outdoor living. They can and will forage, preferring more grass in their diet. They do not sunburn as easily as Large Whites, although they still need good shade.

The breeds I’m outlining here are all rare breeds in New Zealand. Other rare pigs include the New Zealand-endemic Arapawa, Auckland Island and Kunekune.

Black Devon

The Black Devon (also known as the Large Black) is the gentlest of all pig breeds and has an engaging personality.

Some pig people say the floppier the ears of a breed, the calmer they are in nature. Black Devons have the biggest, floppiest ears of all. Their lovely nature can be a problem if they are destined for the table. They happily follow me around the property.

Sally, my Black Devon sow.

All my sows have been quite happy for me to sit in the sty with them, watch the miracle of birth, and handle the piglets.

The meat is tasty and nicely marbled. Jono Walker of Waikato’s Soggy Bottom Butchery grows heritage pig breeds for his business. He says the line of Large Blacks he had were prone to ‘seedy cut’, a dense concentration of black hair follicles that look unattractive on the processed meat.

However, my butcher gets the meat clean and white for me.

Saddlebacks

Also known as Wessex Saddleback, and Hampshires in the USA. It’s another floppy-eared, docile breed, but a bit more protective if you are handling their young.

They seemed to grow faster than the Black Devon and have exceptionally large litters, up to 18 piglets. Their meat is lean with little back fat, tasty, and particularly good for bacon and ham.

Berkshire

This is another good, productive heritage breed. These short-legged pigs are black with white points, erect ears and dished noses. They are reputed to be hardy, fast-maturing and good-natured, doing well on pasture and providing marbled, succulent meat.

- The floppier the ears, the calmer their nature, say some pig people.

- Berkshires have erect ears and good natures.

I am getting a Berkshire sow next month.

Tamworths

These red-coloured, erect-eared pigs are not so docile. They are an active, free-range breed that don’t take well to confinement.

However, they are hardy, excellent foragers, well suited to the outdoors, and produce a firm-textured, lean meat. They are later to mature than Berkshires, and great for bacon.

The problems with eating Kunekune

I never classed the Kunekune as an edible pig until I got served a succulent roast.

The secret is to only allow them to graze on pasture, without supplementary feed. Otherwise, the Kunekune grows a lot of fat and not enough meat.

Kune means ‘plump’ and a Kunekune is doubly plump. When we roasted one for our wedding feast, the fat run-off formed a river from the spit and went across the courtyard. The hungover cleaner-upperers were horrified.

The other problem with eating Kunekune is they are a delightfully placid animal with a wonderful nature. Before you know it, they will be sprawled alongside the kids in the lounge and you will be heading back to the supermarket to buy your bacon.

They are also supposed to be easier to care for, less likely to push through fences or root up the ground like other breeds.

However, some Kunekunes do root, depending on the pig’s temperament, the feed on offer, and ground conditions.

HOW TO BE A GOOD PIG FARMER

5 things every pig needs:

1. Heritage breeds are robust, but any outdoor pig needs shade from hot summer sun and somewhere snug on cold winter nights.

2. A good paddock tree is adequate shade. A temporary house can be made with hay bale walls and a secure, corrugated iron roof.

3. Pigs like to bathe, preferably in mud, but it’s not for vanity’s sake. Water and mud control mites and lice, keep them cool, and prevent sunburn.

4. If there is wet ground, pigs will happily make their own wallow. Otherwise, you can install a sprinkler on a timer or a shower on a solar pump. I have heard of pigs learning to stand on a plate switch to turn the overhead hose on.

5. Pigs need a sturdy trough/s containing fresh, clean drinking water.

Fencing is the biggest issue with pigs. They can and will push through most standard fences. They won’t push against a solid fence. They are also very sensitive to electricity so one hot wire, about 200mm above ground, in front of a normal fence, is usually sufficient around a large paddock.

When pigs are first transported home, they will do anything to escape during the first 24-48 hours. Keep them in a secure pen for this settling-in period, even in the trailer crate if you aren’t convinced your pen is up to the job.

Typically, pigs do not mix well with other animals. I’ve found horses can take quite an exception to them. Cows don’t seem to mind them. I graze sheep in the same large paddock as my pigs. They keep to their own space and I make sure they are separated during lambing time.

Maintenance

Free-ranging, heritage breed pigs have very few health problems. They are very clean animals and will toilet in one area, so intestinal worms are not usually an issue.

My pigs get garlic and chilli scraps (in season) and apple cider vinegar occasionally as a tonic. I have never suffered a noticeable infestation. Your vet can provide an Ivomec injection, which will also treat mites and lice.

A pig roughly equates to 1.6 stock units; it will eat as much pasture and need as much space as 1.6 ewes rearing a lamb.

If you put a ring in the nose of a pig, it won’t dig up pasture, but their small hooves are very sharp and quickly turn soft dirt to mud. I use old concrete posts as a solid foundation around my feeding area and the entrance to the pig house to prevent these busy areas from turning into a muddy mess.

Without nose rings, pigs will root up pasture, roots and soil, effectively ploughing the ground. This is an advantage if you want them to turn over a new vegetable patch but destroys grazing pasture.

One nose-ring through the centre of the nostrils is sufficient for young pigs you are raising for homekill. But a fully-grown breeding pig needs more to prevent them digging up my soft Waikato land.

I experimented with one litter, leaving them without nose rings over a dry summer to see if rings were essential. The damage was not excessive, until we had a nice rainfall. This sparked a digging frenzy. Never again.

The nose is gristle, and I believe ringing is similar to humans having an ear pierced. Apparently, their rooting will also reduce if they’re not mixed with other stock.

Pigs are smart. It is extremely easy to house-train a pig, unlike lambs, ducks and wallabies, which don’t seem to get the concept at all.

Pigs will learn tricks and commands, a bit like a dog. I have trained pigs to sit on command. They have learnt to follow me, and they understand ‘no’. They can also learn how to get through cat doors, open actual doors, and destroy a pantry while you are in town. Be careful what you teach them.

Feeding

Pasture, fruit and vegetable scraps are a large part of a free-range pig’s diet. See the September 2018 issue of NZ Lifestyle Block for information about different feed options you can grow for your pigs.

Pigs need supplementary feeding; the more feed they get, the quicker they grow to killing size.

Pigs will eat almost anything, but you should never feed them raw meat, or scraps that have been in contact with meat. This can spread disease and is against the law. Scraps containing meat need to be sterilised by boiling them for one hour.

Excess milk (not antibiotic milk) from a dairy farmer is a traditional supplementary food for pigs and contains lysine, an essential amino acid. But feeding whole milk can build too much fat on the meat. A roast with 5cm of back fat is not very nice.

I hold the milk in containers. It turns into a very stinky yoghurt and then separates into curds and whey. The pigs love the whey and the chickens love the curds.

Barley is probably the best all-round grain for pigs. Feed it crushed or steeped in water to soften. Meat and bone meal provides good protein.

Pig feed pellets are available from rural supply stores, but I prefer not to feed manufactured or processed food as it negates the benefits of my meat being home-grown.

Killing

As an animal gets older, the meat becomes more flavoursome, but tougher.

A young weaner provides meat that is succulent and delicate in flavour. Conversely, an older pig is more flavoursome, which is great if you’re making sausages.

Once pickled into bacon and ham, toughness is not an issue.

Quantity is usually the main consideration. There is always a stage in a pig’s growth (and all animals) when the feed conversion ratio slows down and it is not economically beneficial to continue to feed them.

For maximum quantity and quality, you need to kill a pig for pork when it weighs around 50kg, around six months for a heritage breed. You grow a baconer on for another few months to reach 100kg (around nine months old).

If you only have two pigs, choose somewhere in the middle and compromise. Killing one and leaving the other on its own will be traumatic for the remaining pig. Keeping a lone pig is also cruel for these very social animals.

‘Finishing’ a pig – the feed it eats in the last week or two before killing – can affect the flavour of the meat. Do not feed anything strong or off in flavour in their final days. Instead, consider apples or acorns.

I use a homekill butcher who kills on my property. This means the pig is happy until the very last second. However, I need to supply a secure yard, dispose of the offal, and supply hot water.

To scald a porker for crackling, you need to immerse the carcass in 60°C water immediately after killing. This removes the dark hairs and skin. All heritage-breed pigs end up white if scalded properly.

I prefer to get my baconers skinned. It is easier, and it means you don’t have a rind on the bacon.

If there is excessive back fat, ask the butcher to slice some off, and you can render it down to lard. You can also use the ‘leaf’ or stomach fat, which is milder in flavour. What you have fed your pig will alter the properties of the fat.

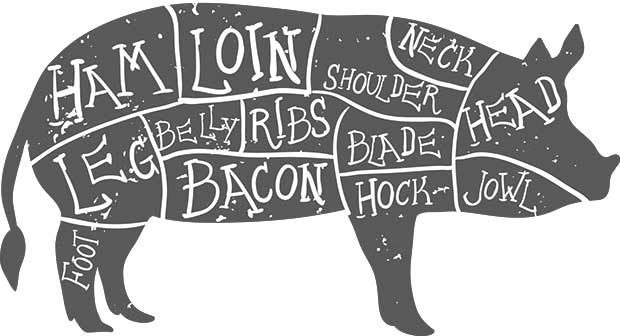

Nearly all parts of a pig can be used. I have experimented with eating pig brain (nothing to rave about) and cleaned the intestines for sausage skins (fun, but a lot of work). I still use the lacy stomach or caul fat to make gourmet meatloaf. The trotters are full of collagen.

I have tried but never been able to collect enough blood to make black pudding. To be honest, I didn’t try that hard. The skin can be boiled and used to make sausages.

Pork is very healthy to eat when pigs are fed natural pasture and food. The meat has a very high mineral content and is rich in a wide variety of vitamins. Pork tenderloin has fewer calories and less cholesterol than chicken breast.

PIG TERMS

Swine: formal, plural name for pigs

Gilt: a female pig that has not yet produced a litter

Sow: a female pig that has had its first litter

Barrow: a castrated male pig (in the US they are called hogs)

Boar: an entire male pig over six months old

Farrowing: giving birth

Piglet: baby pig

Litter: family group of piglets

Weaner: piglet separated from its mother, 6-8 weeks old

Porker: a pig about 60kg live weight

Cutter: between porker and a baconer weight, raised to produce larger joints

Baconer: a pig reared for bacon, slaughtered at 80–100kg live weight

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.