Everything to know about ostriches – and why you don’t want them on your block

Treating unusual species is a regular occurrence for a lifestyle block vet, and this one had a big problem.

Words: Dr Sarah Clews, BVSc

Who: 10 month old ostrich chick

THE PROBLEM

A young ostrich hen, one in a flock of four living in a small paddock, hadn’t eaten in a week. She was sitting down more than usual, separating herself from the others, and seemed weak and lethargic.

A clinical exam revealed she was in very poor body condition. She’d been losing weight over a significant period and wasn’t passing faeces.

Fortunately, she was still fairly bright, alert, and strong. Ostriches evolved in dry, arid environments and can draw on large fluid stores in their body, so despite not having water for a few days, she was managing ok.

It was clear there was an issue in her proventriculus (the true stomach) at the front left of the abdomen. It was noticeably large, firm, and stuffed full of rocks. It’s normal for ostriches to have some rocks in the stomach, but this was an abnormally large number.

THE INVESTIGATION

I did a clinical exam and took a blood sample from a vein that runs up the inside of the leg.

Both suggested she had a chronic stomach impaction and a heavy worm burden. Some studies show that stomach impactions cause as many as 50% of deaths in young ostriches; others suggest the numbers may be higher.

Fluids and other treatments were administered using a stomach tube. Oddly, ostriches stay very calm and still if you cover their eyes.

THE TREATMENT

We treated the hen with fluids and laxatives (psyllium husk and mineral oil) to encourage the obstructing materials to pass through her digestive system, administered through a stomach tube.

She also received antibiotics to cover any underlying or secondary infection, pain relief, and B-vitamins to help her energy levels and stimulate her appetite. She was also de-wormed as parasites may have contributed to the obstruction.

This young ostrich survived her initial bout of impaction and food began slowly moving through her system. However, many aren’t so lucky and require surgery to open and clear out the stomach. Some may also have another obstruction if underlying stress factors aren’t corrected.

Why an ostrich isn’t a really big chicken

Unlike chickens, ostriches don’t have a crop. Instead, food material passes down the oesophagus directly into the stomach.

Like chickens, they don’t have teeth, so they use coarse, non-digestible material inside the stomach to grind up food. Poultry eat tiny stones known as grit, but ostriches have a drive to pick up large pebbles and stones. While it’s normal to find some stones in the stomach, birds may obsessively pick up excessive amounts when under stress. They can end up with a large number of stones or other material in the stomach, obstructing anything from moving through.

The stomach of the ostrich is also unusual. Grazing species like sheep, cattle, and goats are foregut fermenters, digesting food in a big stomach chamber (the rumen). Ostriches are hindgut fermenters, using their voluminous colon filled with bacteria to ferment fibrous food. It gives them the ability to digest fibre from a young age; newly-hatched chicks eat their parents’ faeces to set up a healthy gut biome so they can ferment their food.

In the wild, the ostrich diet is roughly 60% plant material, 15% fruits or legumes, 5% insects or small-sized animals such as rats and mice, and 20% grains, salts, and stones, for a total of about 1.3kg per day. In NZ, ostriches need pellets, maize, and high-quality pasture grass.

They may also eat sand, sticks, and large amounts of dry hay, which can cause obstructions.

7 risk factors predisposing ostrich chicks to obstructions

Obstructions may occur suddenly or slowly over a long time. Those at risk include.

• chicks under 4 months old (easily stressed);

• birds living in isolation, or too many in a small area;

• chicks reared without any adults;

• physical stress such as injury or disease;

• gut infections or heavy parasite burdens;

• moving birds into a new environment, or transporting them to a new home;

• environmental stress such as machinery, dogs, or poor shelter.

The trick to catching an ostrich

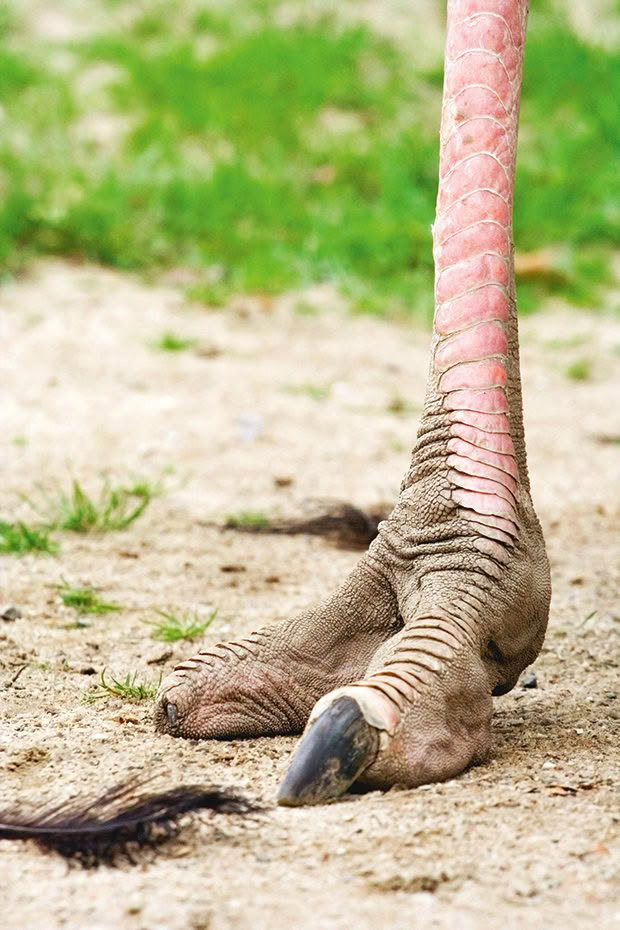

Handling an ostrich is a dangerous business. Ostriches have incredibly powerful legs with two sharp claws on each foot. They kick forward and down: at best, a kick can land you with multiple stitches; at worst, it’s deadly. A forward kick from an ostrich can kill a lion.

Luckily, ostriches act as if they’re sedated when they can’t see. A simple blinding hood can be fashioned out of a loose sock. You grab the beak, then quickly slip the blindfold over the head (making sure to protect their large eyes).

Get someone to hold the head lower than the breast bone which stops the bird from kicking forward. All ratites – including kiwi – kick forward to escape, but blindfolding only works well with ostriches.

DID YOU KNOW?

The ostrich belongs to a family of birds called ratites, which includes rhea, emu, cassowary, and kiwi. Ratites are unique because they have:

• tiny or non-existent clavicles (wishbones);

• flat breast bones

• tiny, stunted wings that don’t support flight.

Ostriches are the largest and fastest birds living on Earth today. In short bursts they can reach 70km/h. They can run much longer distances at around 50km/h, as fast as a racehorse carrying a jockey. They can cover 5-6m in one stride at that speed, the length of a station wagon.

Their eggs are enormous, weighing 1-1.3kg or about the same as 24 chicken eggs. Hens lay in communal nests, which hold up to 60 eggs. Males and females take turns sitting over 42-46 days.

If you crack an ostrich egg and cook it – you need a big frying pan – they’re said to taste similar to chicken eggs but richer and more buttery. If boiled, the white is more rubbery.

The ostrich has the largest eye of any land animal, 5cm across. It means they’re often the first animal in a wild setting to spot predators.

A chick weighs around 1kg when it hatches and stands 25cm tall. At one year, it will weigh about 100kg; by the time it’s mature at three years, it will be close to 3m tall and weigh 160-180kg.

Ostriches are farmed for their eggs, meat, and feathers. Their skin is used to produce a naturally oily leather, said to be six times stronger than cattle hides, and more supple and durable.

Ostriches don’t bury their heads in sand when scared. Their first response is to run, but they may also lay flat to the ground and freeze (hide). The myth may have started when people saw hens digging nests, turning their eggs, or pushing their faces into the sand to find stones.

Ostrich feathers are soft, shaggy, and hang loosely, unlike those of other birds, which naturally hook together to help support flight.

Ostriches uses their wings to balance while running, lowering and raising wings to change direction quickly.

Why you don’t want ostriches on your block

Ostriches are inquisitive, fascinating birds. Some respond well to humans, but you don’t want them as pets.

Despite the domestic ostrich being more docile than their wild counterparts, they’re generally not suitable for close relationships with humans. An ostrich chick – hatched in an incubator – may imprint on a human.

This improves their trust and obedience, and they’ll follow their person for the first few months of life.

However, they can be very dangerous, especially during breeding season when males become aggressive. Imprinted birds may attempt courtship behaviour with humans.

While they might seem like an unusual, exotic centrepiece, they have unique social and physical needs. Chicks easily die from stress, and adults are at high risk of gastrointestinal obstructions due to stress.

Other issues are their lifespan – they live for 40-50 years – and the requirement to keep them behind strong, 1.8m-high fencing.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.