This is why your eggs aren’t perfect

At the first sign of an unusual egg – one without a shell, or those with ridges, pimples or strange markings – the popular advice seems to come from everywhere, but most of it is wrong, and worse, could cause more problems. This is why you need to understand the role of calcium.

Words: Sue Clarke

Calcium is important in the diets of all poultry, but especially in the diet of the laying hen. It’s even more important in those hens which lay a shelled egg day after day for weeks on end without a break like commercial hybrids (Shavers, Hylines).

The amount of calcium available to a bird on a daily basis and its interaction with other essential feed ingredients plays a huge part in whether the bird is able to use the nutrients it takes in. If something is out of balance, it’s going to have problems growing, laying eggs, and keeping its body in good condition.

Calcium must be in balance with two other vital ingredients, phosphorus and vitamin D3. Without the balance of these three, it doesn’t matter how much calcium your bird ingests, its body will struggle to be healthy.

When you read the word ‘balanced’ on a bag of commercially-made feed, it’s telling you the feed contains the correct amounts of each nutrient that a bird needs to be healthy and productive. My impression from talking to poultry owners in person and online is that there is mistrust about commercial feed, but it really does provide everything the laying hen needs.

But it’s this mistrust, or sometimes economic reasons, that leads many people to supplement their birds with kitchen scraps, vegetation, and/or individual grains like wheat to such an extent that birds are not able to get the correct nutrition they require. A bird can only physically eat so much in one day and to be healthy it needs the food it eats to be full of the protein, carbohydrates, minerals and vitamins its body requires.

But if it’s gobbling down kitchen scraps or gorging on grass, it will be diluting the effect of the nutrition it needs because the crop will be full of other things that aren’t as nutrient-dense. When there is a problem like a shell-less egg, or one with strange markings like ridges or pimples, lots of well-meaning advice is offered but it’s rare that it addresses the real cause of the problem: a deficiency in the diet, most commonly calcium and phosphorus.

WHY IT’S VITAL TO FEED EXTRA GRIT SEPARATELY

If you are feeding extra soluble grit to your hens so they can get more calcium, have it in a separate container – don’t mix it into their feed. If you are feeding a commercial feed, they will already be getting the correct levels of calcium. Birds that want more are then free to choose more, but for those that don’t want it, mixing it in will cause them to get an excess, which can cause health problems.

THERE ARE 2 TYPES OF GRIT AND THEY DO DIFFERENT JOBS

Shell-derived grit is known as ‘soluble’ grit. This dissolves in the bird’s gut, allowing calcium to be absorbed into the bloodstream. The other type of grit is insoluble and it serves no nutritional benefit apart from acting as a grinding mechanism by being retained in the bird’s muscular gizzard (not the crop). This is usually small stones or pea gravel that do not dissolve.

PHOSPHORUS

Phosphorous is the second part of the equation and is available from a number of feeds, especially grains. But if a bird’s diet is too high in grain, then the usual ratio of two parts calcium to one part phosphorous is upset, and this will result in an apparent lack of calcium, when the problem is actually too much phosphorous. If you add large quantities of a grain like wheat, ie more than 10% of a bird’s total daily feed intake, it will interfere with their body’s ability to use calcium, not only for shells but for bones and other bodily functions where calcium is required.

WHY YOU DON’T WANT THIS LIMESTONE

Dolomite limestone should never be used for feeding to laying hens as it also contains high levels of magnesium which competes in the gut for absorption with calcium, reducing the availability of the calcium to the bird.

VITAMIN D3

This can be provided from a number of sources. In free range birds, sunlight will have an effect as birds are able to synthesise their own D3. Other sources would be synthetic vitamin D3 which is also added to a balanced commercial feed. Sometimes a shortage of Vitamin D3 can occur if mycotoxins – found in old, rancid or mouldy feed – make it unavailable, which again can mean a bird is unable to utilise the available calcium.

Brown egg laying birds on a commercial feed fully supplemented with Vitamin D3 and also receiving the full daily complement of sunshine of a long summer’s day may suffer loss of pigment from their egg shells, causing previously brown eggs to become pale buff to white. Vitamin D is an important ingredient in shell manufacture and it’s believed an excess interferes with normal production, causing the odd colours.

SOURCES OF CALCIUM AND PHOSPHORUS

Calcium in the diet can be sourced from a number of places. The source used in commercially-made feed is usually limestone flour, but other sources such as bone meal, or meat and bone meal can be added. The level of calcium in limestone can vary according to where it is quarried, but is usually about 38% calcium. Bone meal is around 26% calcium and also contains about 13% phosphorous. Oyster or mussel shells crushed to a manageable size are also a recognised source, along with the crushed shell of the birds’ eggs. Calcium levels in sea shells is also around 38%. Particle size can be critical. You don’t want it too finely ground or it will pass through the bird without being absorbed, or too large that a young bird can’t easily eat it. Another source of calcium and phosphorous is the mineral dicalcium phosphate which is 23% calcium and 20% phosphate.

HOW DOES A BIRD USE CALCIUM IN ITS DIET?

Calcium carbonate makes up almost the entire shell (97%) of an egg. The shell weighs approximately 6g and calcium carbonate is roughly 38-40% calcium so a hen has to mobilise 2.5g of calcium from her blood in the 18 to 20 hours it takes to form a complete shell. The calcium in the shell is derived from the calcium dissolved in the bloodstream from the intestines and is also withdrawn from bone. The bone reserves are replenished during the time the bird is not laying (moulting) and when dietary daily calcium is above the daily needs. Usually a hen can mobilise enough calcium from her bloodstream over the 18-20 hours it takes to form a shell, if she has a diet containing the required amount. If there is a shortfall then calcium is mobilised from the medullary bone into the bloodstream, drawing on her reserves.

A hen requires her calcium intake to coincide with the time the shell is being created (usually late afternoon). This is when you’ll see birds choosing to eat any additional calcium from a separate container or after they have been foraging, in preparation for the overnight shell-making process. To use the calcium in the diet the bird must first break the source (limestone/oyster shell etc) down into calcium ions and carbon ions. These are absorbed into the blood and then either stored in the bone, or recombined to form the calcium carbonate in the shell gland in the oviduct. During this process, some calcium is lost and excreted via the kidneys. That’s why a laying hen providing 2.5g of calcium for her daily egg needs to eat 4-4.5g of a rich, available calcium source to make a shell and allow for the loss.

4 THINGS THAT HAPPEN IF THERE’S TOO MUCH CALCIUM

Too much calcium in a hen’s daily diet can cause a number of problems. A bird might get too much if she’s eating a mix of calcium sources, like fine oyster shell grit, lime flour or crushed egg shells mixed in with her daily feed where she is forced to eat it. This is particularly a problem if the food is fed in a wet mash state, like meal mixed with all sorts of extras which are added in the hope they are doing some good. This is why it’s better to feed oyster shell grit or a similar calcium source in a separate dish so that birds can help themselves. If they don’t touch it, they are getting enough in their daily diet. Higher producing layers (eg Shavers, Hylines) are more likely to access this kind of grit.

1. WET DROPPINGS, SOILED VENT FEATHERS

Excess calcium is flushed via the kidneys. This causes the birds to drink more water which creates sticky wet droppings, soiling the vent feathers and leading people to wrongly think their birds have worms.

2. DEAD BIRDS

By far the most serious consequence of feeding too much calcium is to let chicks and any bird under 16 weeks eat Layer feed which contains high levels of calcium.

The immature kidneys of birds under 16 weeks cannot cope with excreting the large amounts of calcium. Their bodies lay it down as crystals in the tubules of the kidneys over a period of time and a condition known as urolithiasis or visceral gout can be the consequence. This won’t be apparent at the time but can result in sudden death many months later, maybe at a time of stress (when the kidneys fail), often when young pullets are coming into lay or going into a moult. Do not give chicks under 16 weeks access to Layer feed. Chicks aged 0-16 weeks should be on Starter feed, or can be switched to Grower feed at 6 weeks. Broody hens with chicks can safely be fed Starter, along with their chicks, until they are separated.

3. RICKETS

This is characterised by rubbery, bent and deformed long bones in the legs of growing chicks, which can be caused by a shortage of vitamin D3 and/or an imbalance of the calcium/phosphorous ratio. It’s not likely to occur in chicks fed a commercial Starter feed, but more likely when a home produced diet is short in the essential vitamins and minerals, or grain-only diets are fed.

4. PROBLEMS WITH SHELLS

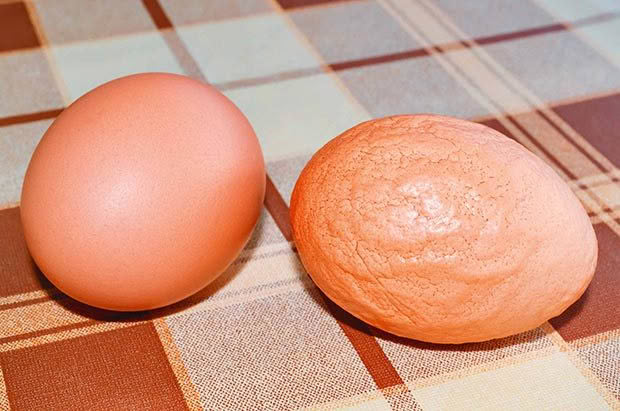

Problems with shell formation are by far the most common result of too little or too much calcium in the diet. Chalky deposits and shells with rough ends are probably a direct result of feeding too much calcium. When the shell has a number of additions – tiny pimples that look like insect eggs – or lumps which when removed leave a hole, or excessive ridges and lumps, it’s mostly like due to an excess of calcium in the diet, rather than a shortage. Hot weather causing reduced food consumption and increased thirst can also lead to a reduction in calcium consumption and reduced shell quality as a result.

An odd-looking shell like one with extra shell deposits can indicate a problem with calcium intake, in this case too much calcium.

While the appearance of an egg with no shell, only a rubbery membrane, or one with a very thin shell which is easily broken sends the message to many that the birds need ‘grit’, it could also be due to many other causes. If the birds are already getting an appropriate amount of Layer feed containing calcium and/or have oyster shell grit or similar provided ad lib, then the cause of poor shells must lie elsewhere, including:

• the birds may just be starting their laying cycle and need time to settle into ovulating and shell making;

• the bird may be ageing and the shell gland not working so well;

• a viral disease such as Infectious Bronchitis or Egg Drop Syndrome can drastically effect shell formation;

• a bacterial infection of the oviduct, like salpingitis can interfere with shell secretion;

• too much phosphorous in the diet (from too much grain) causing an imbalance of calcium to phosphorous ratio;

• the breed/strain of chicken or an individual may have a predisposition

to laying faulty eggs.

Never breed from these birds as the eggs are less likely to hatch due to imperfect air transfer through the shell, and egg shape and shell texture are quite closely inherited.

TIP OF THE MONTH

Has your hen stopped laying? If summer in your part of the country gets particularly hot and humid, it can cause enough stress to a hen to stop her laying. Depending on her age, she may then start moulting – younger birds may start laying again, before their moult begins in autumn. Make sure birds have plenty of shaded areas and multiple water containers that are cleaned and refilled daily, and are also in the shade to keep water cool. Birds can’t sweat so shade and cold, fresh water are the two main ways they cool themselves down. Make sure to have enough areas for birds lower in the pecking order, as they may be squeezed out of both shade and water if there’s not enough room.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.