Clachanburn through the seasons: How Jane Falconer transformed a remote Otago station into a four-season wonderland

Creating a Garden of National Significance in the remote foothills of inland Otago with its extreme climate and heavy clay soil takes a body of strong bones, a will of iron and a soul of magic.

Words: Kate Coughlan Photos: Jane Ussher

This story was originally published in the May/June 2016 issue of NZ Life & Leisure.

Jane Falconer moves like a spirited nor’wester through her garden calling fondly to her spoiled donkeys, Toby and Molly. They honk happily back to her from somewhere in the paddock beyond the boatshed on the lower pond. There are no running shoes or digital fitness devices on this gardening legend for whom most days are a dawn-to-dusk workout.

Jane features in the digital edition of NZ Life & Leisure (May/June #91), read more inspiring stories like this in the digital edition above (click the square to enlarge).

It’s all go in Jane’s two-hectare corner of Central Otago’s remotest Maniototo Plains. She’s never heard of the gear known as “idle”. Neither, it seems, has the John Deere tractor on which she roars forth each morning with its front-end bucket filled with horticultural hardware she might need before the fading of daylight sends her back inside. What that poor tractor misses in rest, it reaps in high praise.

Grandson Charlie Falconer is an eager helper, especially if it involves a good burn-up, driving the John Deere or sitting in his happy place, which is the boatshed.

“It’s my man. I can pick up railway sleepers, stones and small rocks and when I’m finished, I put it in the shed and switch it off. There are not too many men who you can put in the shed and switch off and know they’ll still be there in the morning and not wandered off in an odd direction.”

This slip of a woman, mother of two and grandmother to three, was a freshly qualified home-economics teacher in 1971 when she turned her Mini-Minor off the main highway at Ranfurly and sped along a dusty road through the then blink-and-miss-it town of Patearoa (today having something of a revival) for another 20 kilometres to the foot of the Rough Ridge.

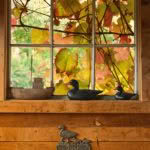

- Jane and “Miracle” Margot Hall (who gardens with Jane one day a week) love autumn for its cooler temperatures, colourful seed heads and the glorious shades of the rowans, poplars and maples.

- The abundance of the fruit orchard harvest is turned into preserves and pastes in Jane’s commercial kitchen and sold in her garden shop.

- The sedum comes into its own in autumn when they glow with candles of red.

- Filipendula pupurea.

She was a new bride, wife to Charles Falconer, whose family had owned Clachanburn Station since acquiring it in a ballot after Second World War and who bred cattle and ran sheep on the flats and the lower slopes of Rough Ridge.

Newly-wed Jane understood the lie of the land as her family property, Gladbrook, lies in a similar north-east-facing valley near Middlemarch 100 kilometres to the south. The garden in her new home, however, in no way resembled the gracious Gladbrook grounds which had been developed by several generations of Jane’s forebears, the illustrious Roberts.

In a previous life the boat shed was the local Patearoa dog trials’ hut but was re-sited by Jane after she had her late husband, Charles, dig her a second pond.

The founder of the Roberts clan (Jane’s great-grandfather) Sir John Roberts was a mayor of Dunedin, chair of many significant 19th-century businesses and institutions, and inducted into the Business Hall of Fame in 2017 — posthumously of course.

The Clachanburn garden was small and tucked like short socks around the ankles of the farmhouse with just one ornamental plum in the handkerchief-sized front lawn and a few flowering plants in narrow beds. Jane took no notice as gardening wasn’t on her agenda.

“When I first came here I thought I’d be heading off each day to teach home economics at a local school. But Charles’ father said, ‘No, your job is to stay home and look after your family. We will not be having people think we can’t support you.’

“This was a most unwelcome shock as I loved teaching and I was good at it, but that was that. I was to stay home and be known as Mrs Charles Falconer. A woman didn’t have her own power in those days, I was an appendage of Charles and it was bloody awful. When you are in this situation, in these isolated places, you just have to try to be happy and find a little path you can go up – maybe sewing, cooking, feeding the family and making a simple happy life for yourself. That path took me to the garden.”

This young wife, and then mother to children Susan and John, was drawn to a valley just below her new home from where she could see the distant Kakanui Mountains and hear a lovely stony creek (which gave the property its name Clachanburn, Gaelic for stony creek). But to do so, Jane had to scramble through a fence and past a large row of poplars and willows.

One sad day Jane found herself sitting at her kitchen table bawling her eyes out. “It was 1985 and my two babies had gone away to boarding school – both on the same day. I was sobbing and going stark staring mad so I told Charles to take out the garden fence so I could create a new garden and have a project.”

She promised the new garden would go only as far as the creek. Initially, Charles wasn’t too pleased as Jane laid out an undulating edge to her garden and if there’s one thing a farming bloke likes, it is a straight fenceline.

- Jane planted deciduous trees for summer shade and winter sun with the lower storey of shrubs being evergreen.

- Winter at this altitude (590 metres) is not for sissies. The ponds freeze over, water freezes in the pipes and Jane has to bash them with a hammer to get it flowing.

- Donkeys Toby and Molly (left to right) earn their keep supplying nutritious garden fertilizer.

- The clinker dingy, which inspired the digging of a second pond, awaits restoration – still.

Knocking down that first fence and several poplars and willows was just the warm-up act for a show that has now gone on for three decades. Stopping at the creek? Today the garden extends twice as far beyond it. Pony paddocks have been eaten up, cow byres have been demolished and majestic pines that once stood lonely in paddocks now live in gardened luxury and brush their lower boughs with elegant shrubs.

However, in the last few years she might have hit the final frontier as the nuttery (her latest extension) meets steeply rising mountainside which even Jane, indomitable as she is, might not be able to conquer. Thoughtfully, she’s left her son, John (now Clachanburn’s farmer), just enough room for a deer raceway between the nuttery boundary and the mountains.

The classic theme of the round garden is reinforced with simple plantings in white and yellow, bare silver birch trunks and rounded forms in the pots and obelisks.

Now he can move Clachanburn’s 4000+ elk between the deer shed, the mountains behind and the flats below. Though she did get him to build the ha-ha of all ha-has – an elk-sized one with schist rocks each the size of a small barn. Not even an elk could leap up its massive sides to wander along a garden path.

Jane says in the early days her garden grew at a slow pace due to her having very little money to buy plants to fill vast empty areas. She went on lots of garden club trips and one day saw a garden with a pond. She realized she had a creek, so she could have a pond and what’s more she had a husband with a wee bulldozer — a perfectly pond-sized bulldozer.

- The view to the Kakanui Range drew Jane out through an original fence, past a line of willows and still gives her daily pleasure.

- Eddie’s White Wonder, the cornus, shows off its spring plumage to great advantage against the red of the maple.

- All the smaller rock walls were built by Jane using rock from the creek running through the garden.

“A fortnight later when Charles was still digging, I said, ‘Charles, when is a pond not a pond? When it becomes a lake. Charles, get out of this pond before it becomes a lake.’ He replied: ‘You’ll thank me for this one day’, and he was very proud of the fact that his pond has never leaked – not to this day.

“A lot of country woman have this same story as mine; their garden growing out through the fences. What do you do with your time and creativity when you are living in very isolated places?

“I was never going to be sitting in the pub. And as far as a golf club went – what was I to be doing with that? Futile if you ask me.”

Granddaughter Lucy with younger brother Charlie riding Spaz and cousin Olivia on Minty are all good riders. Olivia is fearless and jumps against competitors nearly twice her age. Jane thinks Olivia is nearly as gutsy as her mother (Jane’s daughter, Susan) was at that age.

In all lives some rain must fall – though in the Maniototo there’s seldom enough of the real stuff. On the positive side came the commissioning of the Maniototo Irrigation Scheme in 1984. It was a significant development for Jane’s gardening career, ensuring as it did Clachanburn’s water supply.

On the opposite side of the ledger, in 1997 Charles suffered a minor stroke, which shocked the family and left them worrying about the future. Within two years he had another, and this time a major stroke, leaving him wheelchair-bound and the farm teetering on the brink of bankruptcy.

- Clachanburn’s many paths lead visitors on a wonderland-like tour always to a garden seat, a view or to another part of the garden.

- Despite the magical feeling, Jane takes no nonsense from her plants. “I can’t be doing with badly behaved plants that want to bolt out the gate to Patearoa the minute I turn my back.”

- Among her favourite well-behaved plants are viburnum, choisya ternata (orange blossom) and some hebes (the ones that don’t die back in the middle) all of which nicely fulfil the Christopher Lloyd dictum of form, foliage, flowers – in that order.

- Olivia tucks into a muffin.

- Charlie hoovers up Jane’s lemonade at a grandchildren’s tea party in the garden.

- “We don’t have posh plants in this garden,” says Jane of the masses of lupins, catmint, grasses, hebes and roses that flower round the pond in summer. “We plant what does well and that’s what always looks best.”

Jane is sure financial near-ruin caused Charles’ stroke. She and son John (who flew home from elk farming in Canada to take over) worked themselves near to the bone to keep Clachanburn going, took on even more debt in a risky dairy conversion (which worked) and Jane took paying visitors into the garden. Charles died seven years later.

Jane has come to love her garden visitors (about 700 a year prior to the pandemic) and looks forward to seeing them return after the shutdown of March 2020. She particularly loves the international visitors who cannot believe one woman lives alone in such a huge garden.

That makes her laugh and be ever-more grateful for all her good fortune. And for her John Deere, patiently waiting in the garden shed. clachanburn.co.nz

EDITOR’S NOTE

“Most garden photography for magazines takes place in spring and shows fresh growth and vibrant flower colours. But that’s only one act in mother nature’s playbook. In a harsh climate such as the Maniototo’s, each season brings dramatic changes and to fully appreciate their glory we photographed this property over the course of a year. It was worth it.”

– Kate Coughlan, editor of NZ Life & Leisure

MORE HERE:

‘Garden angel’ volunteers transform Te Henui Cemetery into a blooming garden

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.