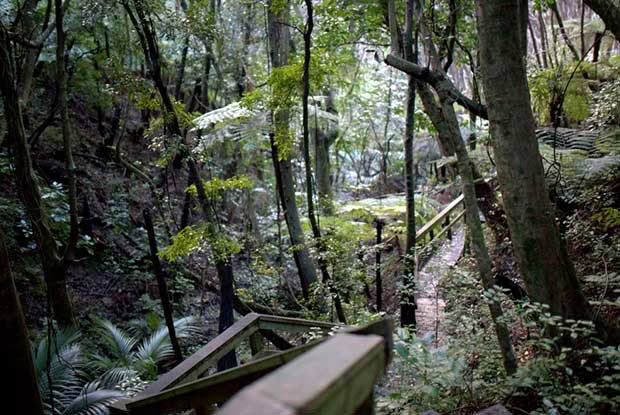

Chris Giblin and Sarah Mathew call Glenfern wildlife sanctuary on Great Barrier Island home

Sarah Matthew and Chris Giblin with Max and Tui.

The only human residents of a thriving Great Barrier Island wildlife sanctuary are fiercely protective of their native neighbours.

Words: Mikaela Wilkes

Waking up at work might not sound like the dream. But for Chris Giblin and Sarah Matthew, birdsong is an alarm, bush-walking their commute and the job of looking after New Zealand’s most vulnerable native species is the best in the world.

Glenfern Sanctuary, where they work, is an 83-hectare paradise of regenerating native bush on Kotuku Peninsula, Great Barrier Island. It is home to many native animals, including black petrel (predicted to be extinct within 30 years), pāteke (brown teal) and the rare chevron skink.

Glenfern’s 15,000 native trees are a living legacy of sailing champion, the late Tony Bouzaid, who began planting his Port Fitzroy property in 1992. The government purchased Glenfern Sanctuary in 2016 and it is now a public regional park. Together with the three neighbouring properties that make up 240 hectares of Kotuku Peninsula, it is protected from rats and feral cats by two kilometres of pest-proof fence and an extensive network of traps (900 now and 1800 by the end of 2018, says Sarah). The sanctuary ensures that some species formerly facing extinction now have a chance to thrive.

Visitor Andie Pyrce gets into the swing of things next to a 600-year-old Kauri tree.

Although Glenfern Sanctuary, which is now owned by Auckland City Council, is only one part of the protected Kotuku Peninsula, Chris and Sarah look after biosecurity for the entire area. “We still pinch ourselves daily.” They were working as DOC conservationists on the Chatham Islands and met Scott Sambell, who previously managed Glenfern with Emma Cronin. “Our ears pricked up when Scott started talking about an opening at this place; the birdlife is immense, and the bush is so lush. It sounded too good to be true, and it is,” says Sarah. “We frantically wrote a CV.”

Pests were eradicated in 2009 but didn’t stay away for long. Reducing populations of rats, feral cats, pigs and rabbits is a never-ending battle. “Glenfern’s pest-control fence encloses one-fifth of the property but doesn’t extend to the low-tide mark so, at times, feral cats can walk right in. It doesn’t help that rats can swim two kilometres, either,” says Chris. They are both aware that they may not see the rewards of their current work in their lifetime. “Conservation is an incredibly slow process,” says Sarah.

SNAPSHOT

Chris has a degree in environmental science and marine biology. Out of university he piloted boats for DOC in the Hauraki Gulf for eight years. Sarah studied fine arts (photography and sculpture) before joining DOC as a volunteer and then becoming a ranger. They met when Chris signed off Sarah’s boat licence, and have since worked as a couple. Their pets, Max and Tui, black labrador conservation dogs, are integral to the team and are in charge of hunting feral cats.

TIMELINE

1992: Tony Bouzaid begins planting native trees.

1996: First predator control begins with cat trapping.

2008: Predator-proof fence installed.

2011: Duck pond created for pāteke habitat; Sam and Emma take over management.

2017: Chris and Sarah become managers.

2018:

• 200-hectares of previously farmed land restored to native bush.

• 1000 bait stations and tracking tunnels under monitoring to prevent pest invasion.

• 7 pāteke babies born this season.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.