How to build a house of hemp

When you take the magic ingredient out of marijuana, you get a building product to keep you warm, cosy and very happy.

Words: Nadene Hall Photos: Jane Dove Juneau

Who: Matt Low, Melissa Burleigh-Low & son James (4)

Where: New Plymouth

Land: 4ha (10 acres)

What: hemp house, permaculture garden, composting toilet,BioGro-certified organic feijoa orchard

A hawk banks lazily in the wind over the top of Kāhu Glen. They often float their way over Matt Low and Melissa Burleigh-Low’s block, drifting on the winds which gust in off the Taranaki coastline just a few kilometres away.

Far below, Matt and Melissa aren’t too bothered. They tend to enjoy mostly wind-free days, tucked in behind the commercial shelterbelts they inherited when they bought a former feijoa orchard.

“We can sit here when it’s windy in a t-shirt and shorts and then go into town and you need a jumper,” says Matt. “The shelter makes such a huge difference.”

Their feathered visitors were the inspiration for naming heir block Kāhu Glen. Kāhu is the Māori word for the hawk (technically the harrier hawk, Circus gouldi), while ‘glen’ is Scottish for valley, a nod to Melissa’s heritage.

In their own wee glen, tucked away from the prying eyes of neighbours, is a permaculture-designed garden and an organic orchard that produces around nine tonnes of feijoa a year which the couple have processed into juice for sale. They can see the fruits of their labour out the curtain-free windows of their unusual home that sits at the heart of their land and which was inspired by a man named Lance.

“Lance (Palmer) owned a building company,” says Melissa.

“He’d done a lot with buildings and knows the Building Code inside out. He did a hemp and solar technology workshop and he was quite sold on the ideas and he went into researching it quite a lot.”

The hemp plant looks like its close relative, cannabis.

It was Lance who convinced the couple they could be owner-builders of a hemp house which would become only the second to be given consent in NZ.

“He said ‘you’ve got an engineering background, you’re practical, you’re more than capable’,” says Matt, who works as a civil engineer.

“With (Lance) we got to share a lot of the cost of importing the hemp in, we worked together… he’s been a tremendous help right through the process.”

Matt, James and Melissa in the garden, standing on the end result of their composting loo.

READ MORE: Matt and Melissa share their experiences installing a composting loo.

When you’re one of the pioneers of a hemp home, you have two jobs: to build your house, but also to convince the local council that hemp is a great idea. Step up Lance.

“He built a little prototype, 600mm long and 400-500mm high and had the framing, had it all made up and partially plastered,” says Matt. “He took it into council and said ‘this is what I’m doing’.

“When he was partially through (his build), he got all the local building inspectors out to his place for a couple of hours, took them all through it to show how it was working, because no-one was experienced either from their side.”

The unusual windows tilt rather than open.

A new kind of building technology is always a challenge for a council, which has to interpret the Building Code.

“I think there was a lot of internal discussion (at council) about what was the liability and risk they were taking on?” says Matt. “But they decided to give it a go, and they certainly helped out a lot through the process.

“I think the biggest thing for them was the weather tightness. I wrote pages on flashing details and external joinery, there were quite a few revisions.”

A standard timber-framed house will have a cavity, a small air gap between the frame and the outer cladding, to keep moisture out. There is no cavity with a thick, solid hemp wall, so Lance and Matt turned to the technical standards for rammed earth homes and followed many of their specifications to reassure council it would work.

“Because it’s new technology, the council staff often didn’t really know what they were looking for because there’s no pre-line inspection. The traditional inspection list was modified a bit to suit! We ended up with one inspector who saw most of it through to the three-quarter mark, and we got him back to do the final inspection.”

THE BEST THING ABOUT LIVING IN A HEMP HOUSE

That’s the insulation and the heat says Melissa.

“It’s absolutely phenomenal. We have a fire in winter but you chuck a couple of logs on it and then let it go out because it heats the whole house. We put in frames for internal doors to be able to cut the lounge off (from the rest of the house). We’re now debating whether we build the doors because we just don’t need them.”

James sitting in a bale of hemp.

ABOUT THE HEMP HOUSE

Area: 170m²

Floor: insulated concrete

Framing: timber

Walls: hemp (Hemp Technologies), lime, water mix

Windows: western red cedar, double glazed (Optimal European Windows & Doors)

Power: grid-tied, 5kw solar array on the roof for water heating

The cost: Matt and Melissa haven’t finished building their home but they estimate the build will cost around $400-430,000 ($2500 p/m²) on completion. This figure doesn’t account for Matt’s time working on the design, project management, material procurement and construction. The total hours spent constructing the hempcrete walls was approximately 700 hours for the 170m² house.

“We were all learning the process and we taught a lot of people skills as we progressed through the build. Doing it again there would be more efficient ways to work with the hemp.”

Hemp may look like the kind of thing you dry and smoke, but it’s a particular variety of Cannabis sativa and it’s missing the magic ingredient. In NZ, it must contain no or below 0.35 per cent tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is what gives marijuana its psychoactive effects.

It grows fast in New Zealand, yielding around 10 tonnes in just 126 days, but the fibre that was the building block of Matt and Melissa’s house came all the way from Europe.

“Local people are growing it and we did look at it,” says Melissa. “But they don’t have any of the equipment to process it here so it ended up being imported from the Netherlands.”

The ‘hempcrete’ is a mix of hemp, lime and water, and is compacted into 100mm high layers.

The hemp stalk has a hard fibre on the outside that needs to be stripped off. The material in their walls is the soft cellular centre which is broken down into a very fine chip, then compressed into 800cm x 300cm x 400cm bales and wrapped in plastic for transport.

Once on the building site, Matt and Melissa created ‘hempcrete’. The hemp was mixed with a lime binder (lime and water) in a paddle mixer until it was a porridge consistency. Once it holds together in a ball, it’s ready to go.

The shutter system was created by builder Lance Palmer to help make creating the walls easier.

It was Lance who came up with a method to make things easy for the first-time builders, creating a shutter system that could be easily lifted into place as each wall got higher.

“The house structure is all timber, standard timber walls and framing,” says Matt. “When you’re building you put the two shutter boards down either side of it. We had the frame in the middle, then put a shutter 100mm on either side so (the wall) was 300mm thick. Then you basically empty your hemp mix into wheelbarrows and tip it into the shutters.”

Once a section was full, Matt and Melissa used blocks to hand ram it into 80-100mm thick layers. Then they’d lift the shutters and repeat the process to build the wall up.

Ordering the right amount of hemp was tricky, and Lance was on it.

Lifting hempcrete into the top of a wall.

“We didn’t really know ourselves how much we’d need,” says Matt. “But Lance did a little trial 3m x 3m shed which became a chicken shed. He started playing with mixes, worked out quantities and ratios, whether one was too dry and because it was too dry, it was too brittle. He worked it all out.”

Their north-facing house follows passive solar principles. Its insulated concrete floors gather in the sunlight in winter.

“It rarely gets below 16-17°C even on the coldest day in winter,” says Melissa. “Then you light the fire and it’s up in the 20s really quickly.

Opening a window in this house is a European affair, with each one tilting and tipping inwards, giving a 50-80mm gap so they are still secure but there is plenty of cross ventilation, with air easily flowing through the house.

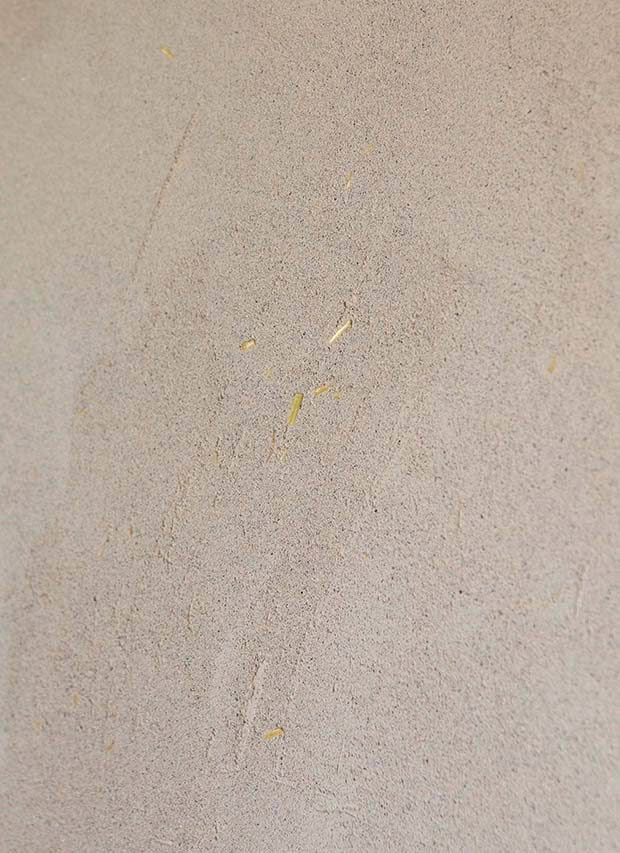

The finished wall shows lines denoting each layer of hempcrete.

“All the windows are made of western red cedar,” says Melissa.

“It’s a European design because we couldn’t have aluminium next to the hemp/lime mix – it corrodes it – and we didn’t want aluminium anyway. It wasn’t the look what we wanted to achieve.”

The hemp walls are covered with a lime plaster inside and out, except for one indoor ‘window of truth’ (see below) to show visitors what the hemp looks like.

“It’s quite a breathable building material, so it regulates a bit with the seasons,” says Matt. “Moisture and humidity closely control themselves – you haven’t got a hard cavity system so there’s no sudden change.”

The outer walls have an adobe finish – “enough so you can hide your imperfections as a plasterer,” says Matt – with a colour mixed into the plaster so they didn’t have to paint it.

The hemp walls are 300mm thick, and once finished, were coated with plaster, and then a water-repellent product.

It was then coated with a water-repellent product, allowing it to maintain the ability to ‘breathe’ but rainwater ‘beads’ on the surface and runs off.

“You certainly can hose it down, you can use a brush that’s attached to a hose and scrub it as you go,” says Matt. “It’s hardened off and it’s quite a durable material but I think if you sat there with a water blaster for too long you’d get a hole.”

This very warm house doesn’t cost much to heat other than firewood. The monthly power bill is about $90.

“We have a 5kw PV (photovoltaic or solar panel) on the roof of the house, but we’re also grid-tied (able to draw power from the grid),” says Melissa. “We looked at batteries and going off the grid at the start but we didn’t know where to put the PVs.

Matt with the ‘window of truth’ showing the raw hempcrete wall.

“We decided to go grid-tied because the technology just wasn’t there at that stage, and you still have to replace (batteries) every eight years. You times that by two and the cost of getting the cable to the road made more economic sense.”

They use the solar panels for power and to heat their hot water. If there’s any excess, it goes back into the grid.

“Basically, we don’t have to pay for hot water because it’s generally done by solar.”

ADDING THE ALL-NATURAL GLITZ

The plaster on the internal walls has a special, all-natural ‘glitter’ effect added to it, made using a coffee grinder, a fine sieve and a pot scrub.

“I saw it in a Japanese tea house and I really liked the look of it and asked what they did,” says Melissa. “They used straw so we added it into the plaster. I put it through a coffee grinder, then I put it through a couple of sieves to make it really fine, almost glittery – slightly bigger chunks than glitter.”

They then used a pot scrub to sand down the walls, revealing the little chips of straw, which give the walls a golden fleck effect.

“It probably would have been best to put it on the walls that get a bit more sunlight,” says Melissa. “You probably wouldn’t notice it when you first walk in, we often have to point it out.”

WHAT YOU CAN DO WITH 100,000+ FEIJOAS

Matt and Melissa’s block was originally home to 2000 feijoa trees. The previous owners were commercial growers Linda and Trevor Swan; Linda’s father, Dennis Barton, developed feijoa varieties including Unique (the one you’ll find in most backyards), Barton and Den’s Choice. The Swans thought no-one would be crazy enough to buy land with that many feijoa trees, so they chopped out 1500 and left Matt and Melissa with enough to keep them out of trouble.

The couple processed nine tonnes of feijoa in 2017, turning most of it into their own juice products.

“We touch-pick them so they don’t fall off the tree,” says Melissa. “That’s so that they don’t bruise and they have a longer shelf life. They go off to Turners and Growers and supermarkets, and we sell them at the local farmer’s market, at a couple of little local stores, and at a friend’s roadside farm shop.”

Their first crop was just a couple of tonnes, but it was enough.

The feijoas are the remains of a much-larger orchard and feature original varieties by renowned growers Linda and Trevor Swan.

“The first year we basically would pick and sort it all by hand, and we working up until 10-11pm every night,” says Matt. “We’d just had James – he was born during the second week of the feijoa harvest – and if we had done nine tonnes back then I think we’d probably have bulldozed the lot.”

Things took a turn for the better when the Swan’s sold them their fruit grading machine, which sped things up dramatically.

“Initially it was quite funny,” says Melissa. “I couldn’t understand why Matt wanted to spend more money on these bloody feijoas! Then after the first year I was like ‘I get it, I’m glad we bought it’.”

Selling fresh fruit only gets rid of so many feijoas. The answer to the glut was to turn it into juice.

“We send it up to Greenways Juices (in the Waikato) and they make it for us. They’ve got a big commercial juice press that does two tonnes per press so we grow it, they send it back and then we sell it. They do a lot of juice themselves so we buy apple juice from them and they mix it.”

The sheep keep the grass down, and are eventually turned into the family’s homekill meat supply.

THE PERMACULTURE GARDEN

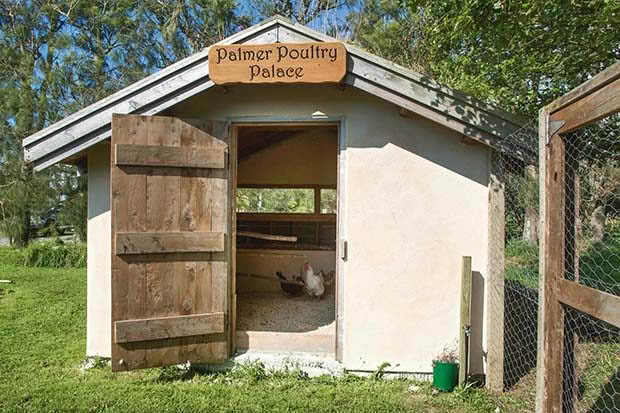

When Lance Palmer built a prototype hemp building, he gifted it to Matt and Melissa for their permaculture garden. They turned it into the most well-insulated hen house in NZ, complete with a green roof.

The garden also has a topbar beehive, sheep, turkeys, and cows running around the pasture.

“Self-suffciency is probably not the goal, but it is the direction we want to go in,” says Matt. “We’ll never be completely self-sufficient, but we haven’t bought meat or eggs from a supermarket in years.”

The only veges they buy are mushrooms, peas and carrots.

The garden will eventually expand, but right now the only vegetables the family needs to buy are carrots and mushrooms.

“I have to buy carrots because Taranaki soil is so fertile your carrots end up like forks,” says Melissa.

Their garden is still a work in progress but is based on a permaculture design, part of another stroke of good luck.

“We won a competition run by Greenbridge (a sustainable property design company), about $800 worth of consultancy fees. It’s kind-of permaculture design and they helped plan it, and they also helped us out with a 12 month planting orchard, helped us pick the trees, so we get fruit right through the year. The maps they do are awesome, and you get a calendar with months of the year in a circle and what fruits you get.

Friend Lance Palmer built the hen house as a structure to test hemp mixes. He gifted it to the couple for their flock.

“We’ve got the base orchard planted out, the apples, pears, peaches, that sort of stuff, but we haven’t quite finished developing the subtropical garden, that’s mainly a big topsoil pile outside the house.”

In permaculture there are no lawns, but on this block, there is James and he needs a lawn says his mum.

“I was like yeah, nah! Out front of the house is north-facing and beautifully sloped and I want lawn in front of my house. I don’t want to look at my veggie garden when it’s in a state of disarray, that can go out the back.”

The couple have also planted out trees around the wetter areas of their property, and say they can already see a difference in the water quality on their side of the fence.

“We’ve done a couple of riparian planting blocks,” says Melissa. “When we came here one hill was completely covered in gorse – it would have been over Matt’s height in woolly nightshade too. We’ve had friends spend hours with us on weed whackers.”